Think differently. Think archetype. Your digital economy model.

A novel approach to digital transformation and policy reform

Executive Summary

Introduction

Today, most countries strive to achieve strong digital economies, yet there is no standard model to follow, and success stories remain limited. Our study proposes a uniquely structured approach that is specific to the varying capabilities, resources and ambitions of different countries. It is designed to help policy makers create tailored strategies to achieve both their mid-term digital ambitions and longer-term visions.

Digital transformation can result in long-lasting benefits for economies

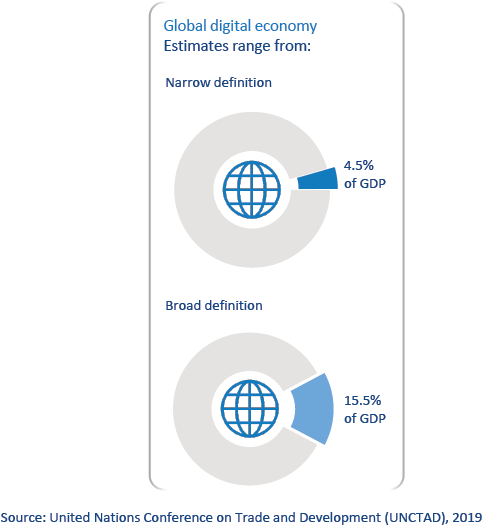

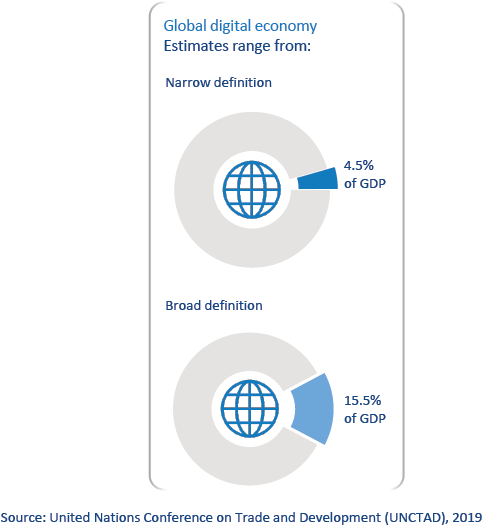

The digitization of economies delivers numerous benefits, driving innovation, fueling high-paying job opportunities and boosting economic growth. Depending on the definition, the digital economy represents between 4.5 and 15.5 percent of the world’s GDP.

Digital infrastructure is the basis for industry and the economy as a whole, forming the foundation for the higher layers in all value chains. This is increasingly becoming the case as most economic sectors undergo digital transformations. Without highspeed and pervasive connectivity infrastructure, there can be no digitalization – for nations of any size.

Transitioning to digital economies can enable countries to boost industry growth and productivity, improve societal well-being and benefit consumers via cost or time savings. Digitalization will help bring about new opportunities for businesses and/ or improve productivity in industries such as manufacturing, agriculture and energy & utilities. It provides new tools for tackling persistent development and social challenges and improving access to healthcare, education and other public services. Consumers also benefit through faster access to better products and services at lower costs. Consequently, the transition to a digital economy is a major policy priority for all countries.

A study conducted by Oxford Economics and Huawei, which captures the value of digital spillovers, estimates that in a highdigitalization scenario, the global digital economy could grow to account for 24.3 percent of global GDP by 2025, which equates to $23 trillion.

Embracing digital needs: a tailored approach

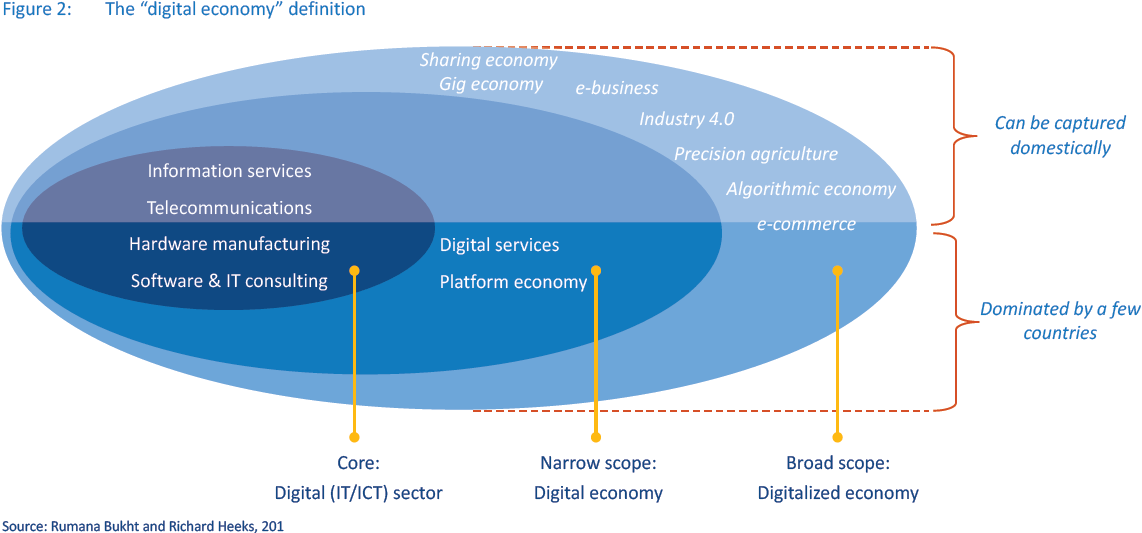

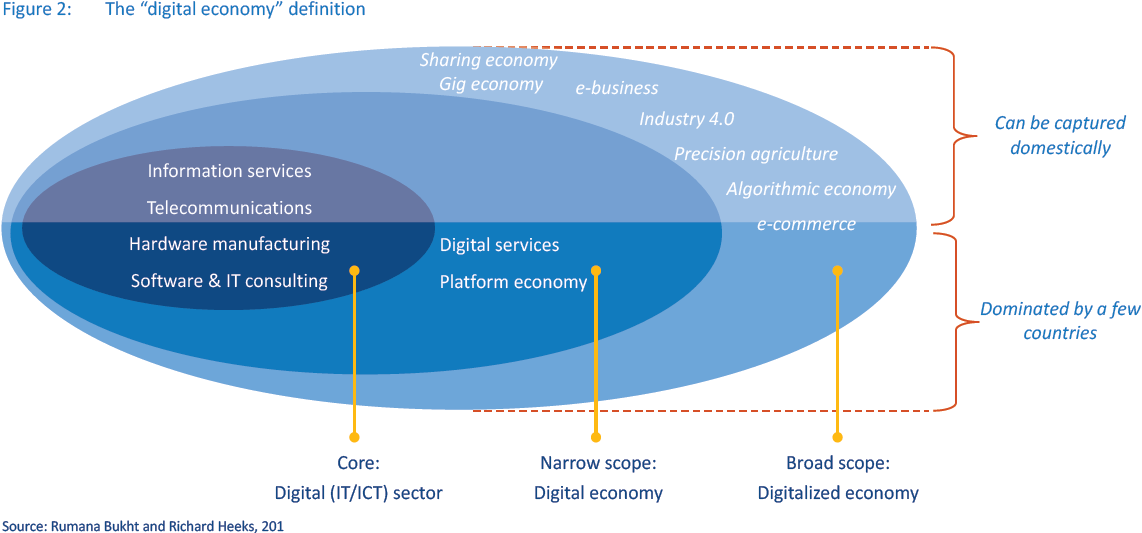

A digital economy consists of many aspects. Certain parts of the global digital value chain are dominated by a few countries – for example, software services in Ireland and Philippines, and hardware manufacturing in China. Contrastingly, other elements of the digital economy are intrinsically local – for example, e-government, e-health, support services and connectivity.

As policy makers consider different options and practices aimed at maximizing benefits from the digital economy, they need to recognize that “one size does not fit all” when it comes to digital policies. For example, Germany launched its artificial intelligence strategy in 2018 and allocated a €3 billion investment to AI R&D, estimating that AI would add approximately €32 billion to Germany’s manufacturing output over the subsequent five years (2019–2023). Should policy makers working in the least-developed countries also aim to invest their limited resources in AI and expect the same returns? The obvious answer is no. Every country is unique or can be characterized by a distinct set of national digital traits. The challenge is to identify what individual governments should focus their national efforts on and how they should do this.

Allocating scarce resources and finite funds according to a country’s specific context is crucial, particularly if the huge development gap which exists between under-connected developing countries and hyper-connected digitalized economies is to be closed. ICT policy making is extremely complex and decision makers are often overwhelmed when considering the factors involved. Most countries are short of resources and not integrated with the global ICT value chain and lack sufficient skills to develop their local ICT industries. And many of the factors required to develop a domestic ICT sector have long gestation periods – for example, developing local ICT talent can take years, and making an impact in basic research requires sustained effort and substantial funding over many decades.

As such, policy makers – particularly those in developing countries aspiring to create large numbers of ICT jobs – need to align their resources strategically. This is akin to developing a strategy for a company. Successful companies choose to define their strategies by aligning all their resources to solitary objectives – either to be the lowest-cost producer (e.g., BIC makes disposable consumer products that offer simple, affordable solutions to everyday needs), supplier of the most differentiated product or the provider of a niche product/service (e.g., telecom operators offer services within defined geographic regions).

To support policy makers in their thinking and help develop their strategic focus, we have distinguished a number of different digital economy archetypes. This enables nations to take a tailored and distinctive approach to aligning their digital economy policies and objectives.

Our analysis of the ICT value chain includes detailed benchmarking of beneficial policies and capabilities in 15 countries, discussions with experts in national digital transformation and the ICT market, and a literature review – it also leverages Arthur D. Little’s project repository of national ICT strategies and industry experience. Through this, we have identified seven digital economy archetypes: Innovation Hubs (IH), Efficient Prosumers (EP), Service Powerhouses (SP), Global Factories (GF), Business Hubs (BH), ICT Patrons (IP), and ICT Novices (IN). The archetypes differ in their presence or dominance in the ICT value-chain step, as illustrated Figure 1 below. However, archetypes are not limited to specific steps in the value chain – instead, their position marks the focal domain in the overall value chain. They can be further differentiated through other underlying characteristics, such as economic

status, population size, political stability, geographical advantage and technology penetration. In addition, country archetypes guide policy priorities.

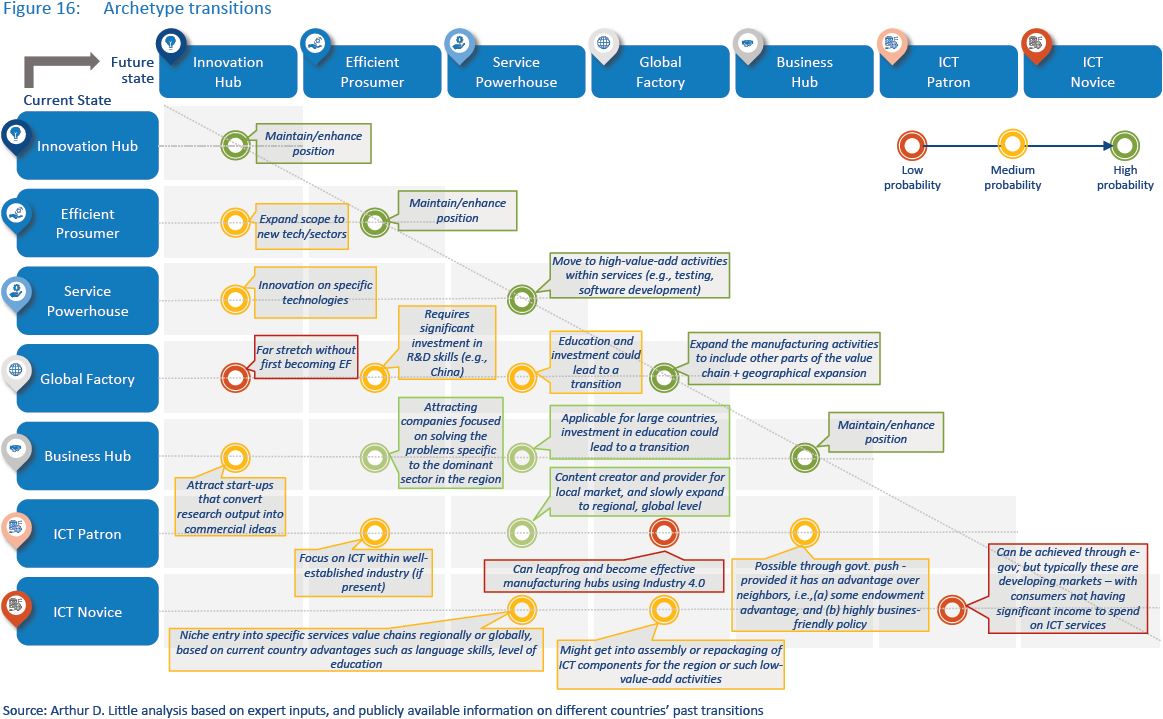

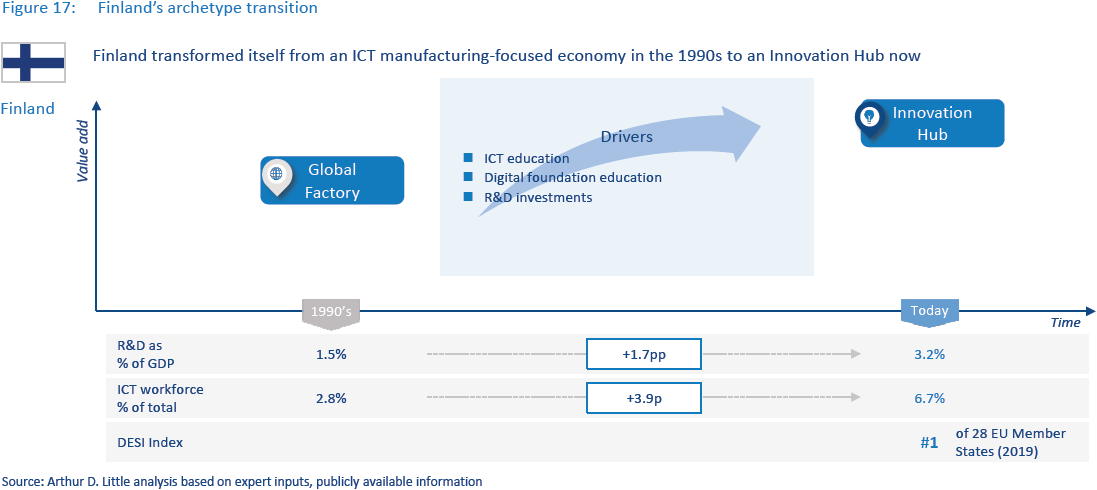

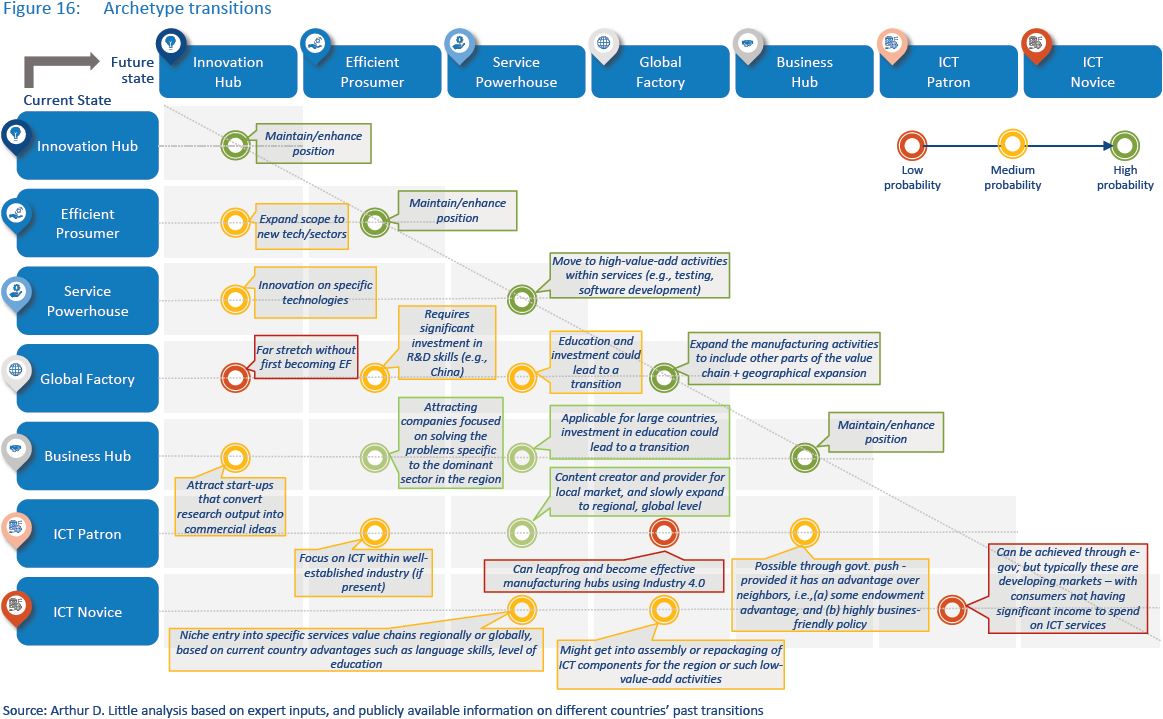

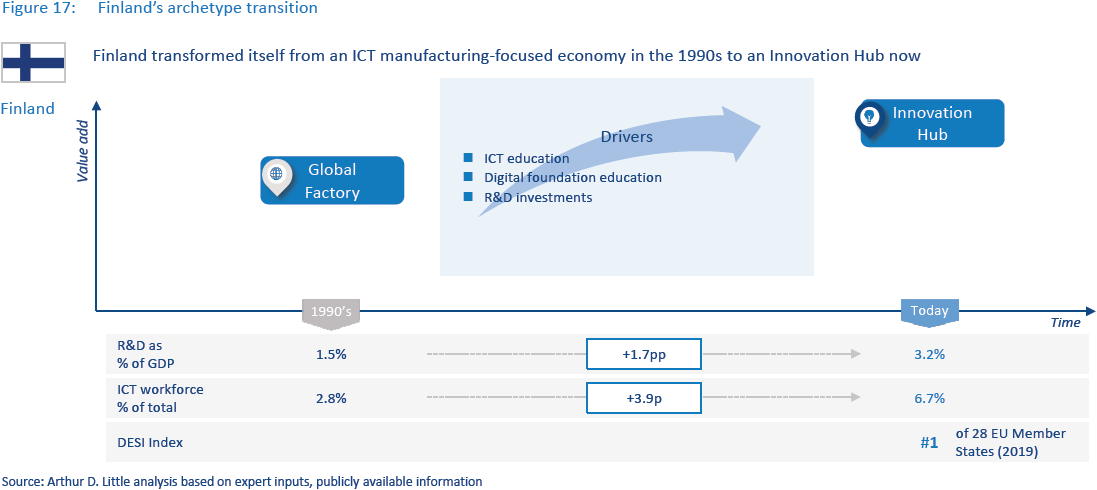

Mapping countries onto archetypes has resulted in two key insights. Firstly, archetypes are not mutually exclusive, and a country may also present (some) characteristics of a second archetype. Secondly, transition to a higher-value-adding archetype is possible and even desirable but takes concerted effort. For example, Romania has transitioned from an ICT Patron to a Service Powerhouse (especially in cybersecurity services), and Mexico has transitioned from ICT Novice to Global Factory. Romania was able to leverage its institutional legacy of excellence in science, mathematics and technical education, its large domestic market of 20 million population, and lower costs to become a favored IT outsourcing destination for European clients.

Charting a unique digital path and redefining policy priorities

Nations need to develop digital value creation paths that align with their most suitable archetypes, leveraging their inherent strengths, but anchored by their economic and technological realities.

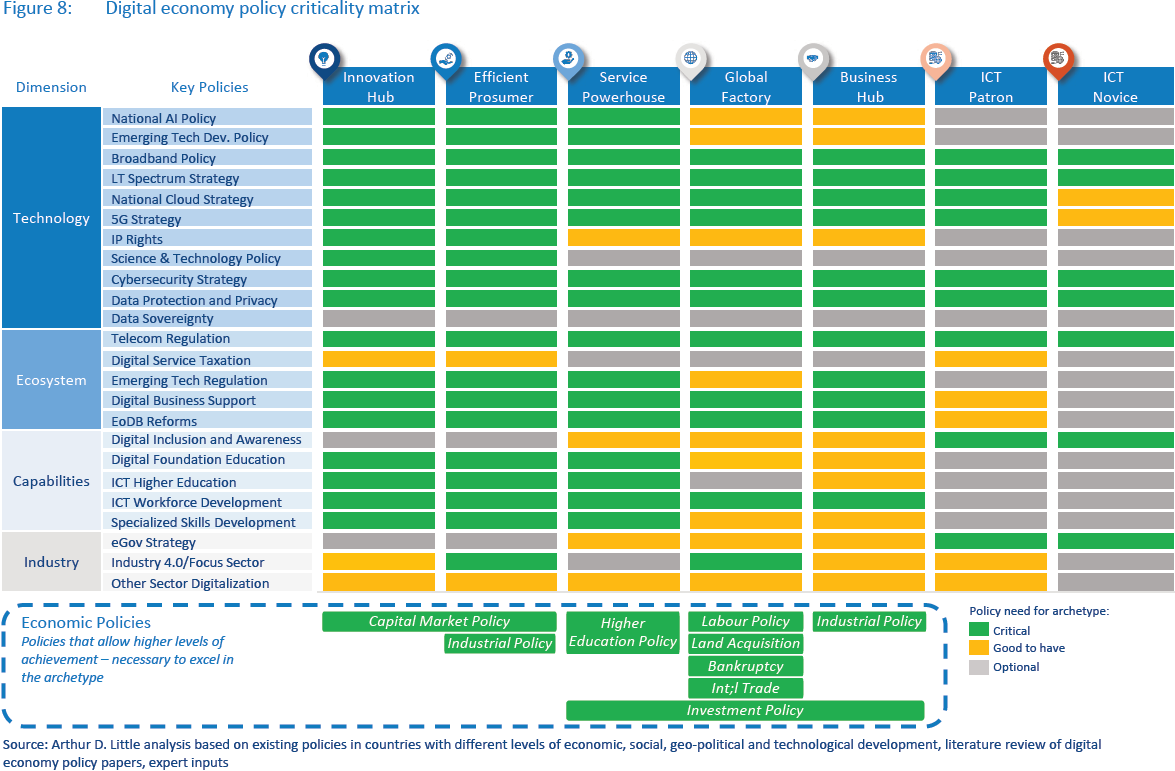

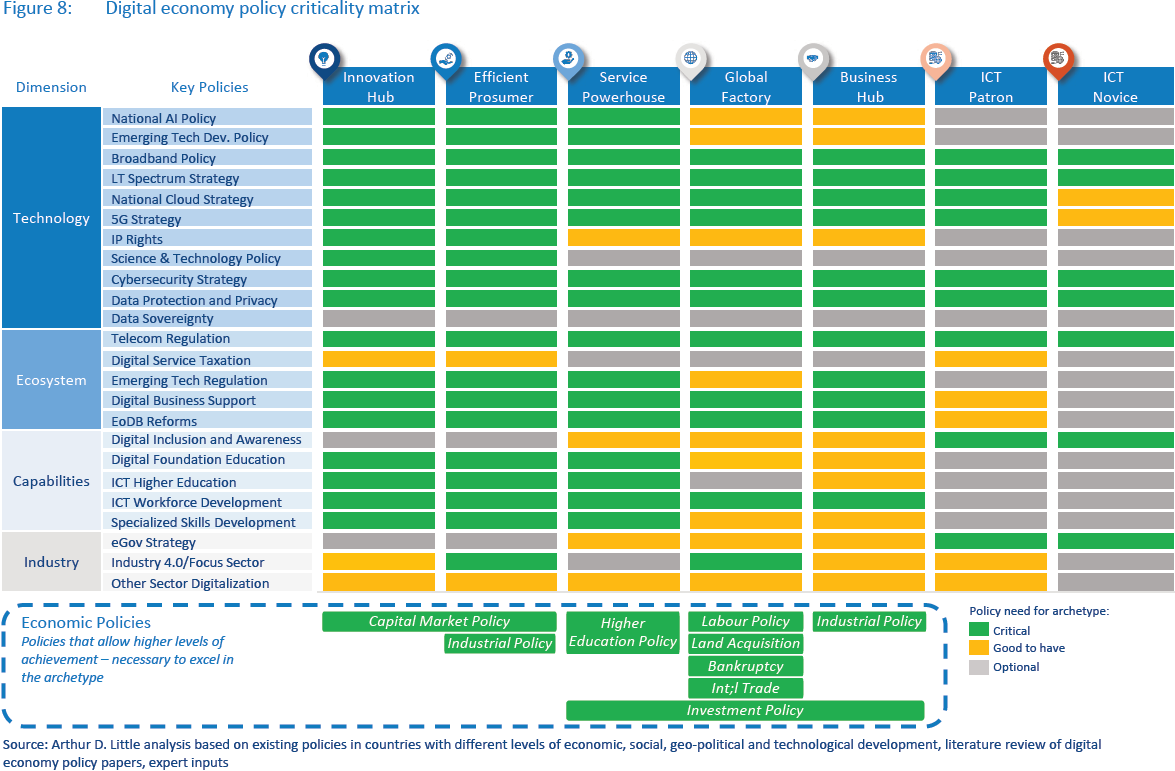

Policy makers need to formulate policies, laws and regulations across four interrelated policy dimensions – technology, capabilities, ecosystem and industry – as we believe these to be the driving forces underpinning digital transformation.

- Technology

Most countries need better connectivity. Irrespective of the national archetype, governments must address policy and regulatory issues relating to broadband, spectrum, cybersecurity, data protection & privacy, and cloud computing.

A best practice 5G strategy is essential to support the introduction of new applications and services that need higher communication speeds and lower latencies. This is critical for all archetypes except for ICT Novices, whose primary focus should be on deploying mature communication infrastructure (4G, fiber) before investing in 5G.

However, for other emerging technologies, we believe the best approach should differ across archetypes. For example, national AI policies, emerging technology development policies, IP rights regimes, science and technology policies focused on cutting-edge technologies, and IP generation and commercialization are all critical for Innovation Hubs and Efficient Prosumers. Service Powerhouses also need national AI and emerging technology development policies, but the focus here should be on building workforce skills in emerging technologies. This will allow companies based in these countries to remain competitive and improve their service-delivery capabilities.

- Capability

The capability development and resources assigned also differ across archetypes.

For Innovation Hubs, Efficient Prosumers and Service Powerhouses, the focus should be on developing digital foundational skills, ICT higher education and specialized skills.

On the other hand, ICT workforce development policies are critical for Global Factories and Business Hubs, as they need to access talent to sustain their digital economy models.

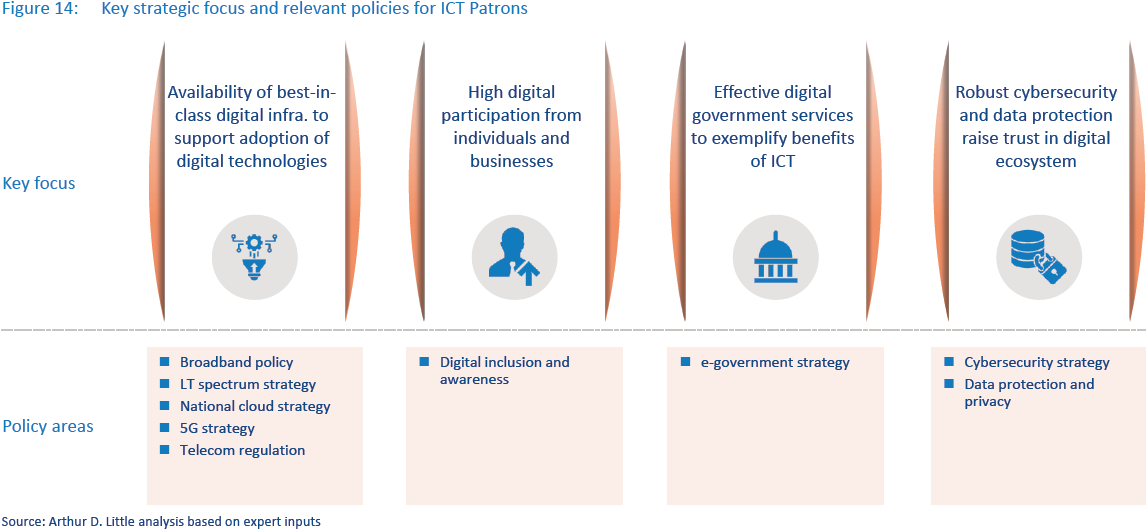

ICT Patrons and Novices should focus their resources on improving digital awareness among both individuals and businesses.

- Ecosystem

Digital business funding and support policies and ease-ofdoing- business (EoDB) reforms are critical for Innovation Hubs, Efficient Prosumers, Service Powerhouses, Global Factories and Business Hubs because they need to attract private sector investments, particularly in domains that support their archetype strategies.

Emerging technology regulation is critical for Innovation Hubs, Efficient Prosumers, Service Powerhouses and Business Hubs, as they need to offer conducive environments for digital businesses to test new technologies and innovate.

- Industry

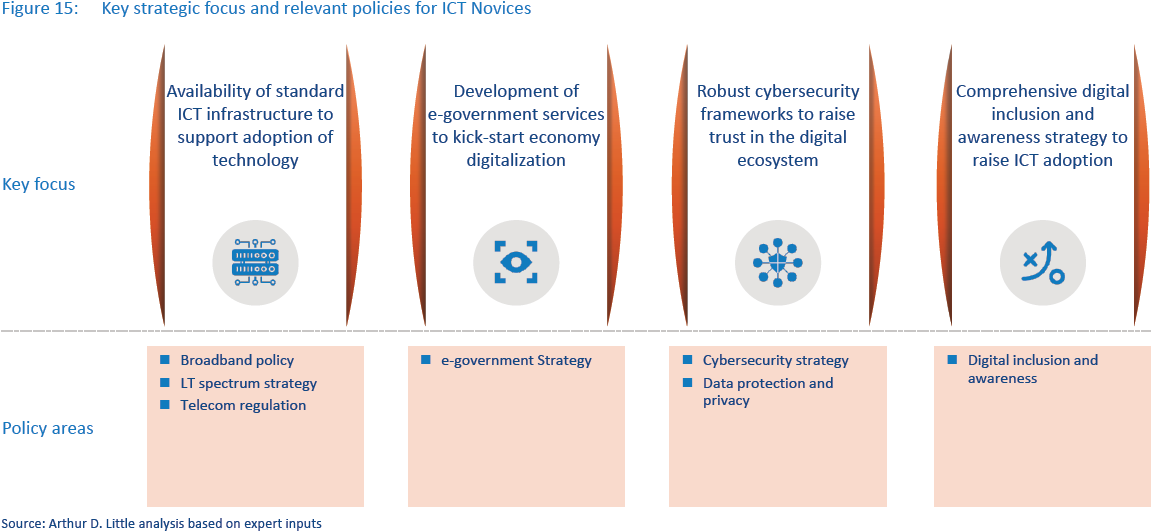

ICT Patrons have used e-government strategies to kickstart digital-capability building and increase awareness and digitalization of other sectors in these economies. This is also critical for ICT Novices to stimulate digital services demand in their economies. Typically, other archetypes have implemented e-government strategies in the past and do not necessarily need to focus on this.

Industry 4.0 policy is critical for Global Factories and Efficient Prosumers in order to maintain manufacturing competitiveness in the digitalized world, as well as in traditional manufacturing.

Other sector-specific digitalization policies are good to have across all archetypes, but they should focus on their respective dominant industries.

The importance of digital economy policies varies fundamentally between archetypes. Different combinations of policies should be considered for different archetypes. This does not mean countries should disregard other policies, but instead they should ensure that policies critical to their archetypes are given due resources, budget and attention first. These tailored and specific “recipes for success” should shape the strategy each country deploys to build its own digital economy.

The incentive for digital transformation is clear – and the need to embrace change has never been greater. However, nations will only realize the full benefits of this transformation if their digital strategies are built on their own strengths, and their digital policies are prioritized and focused.

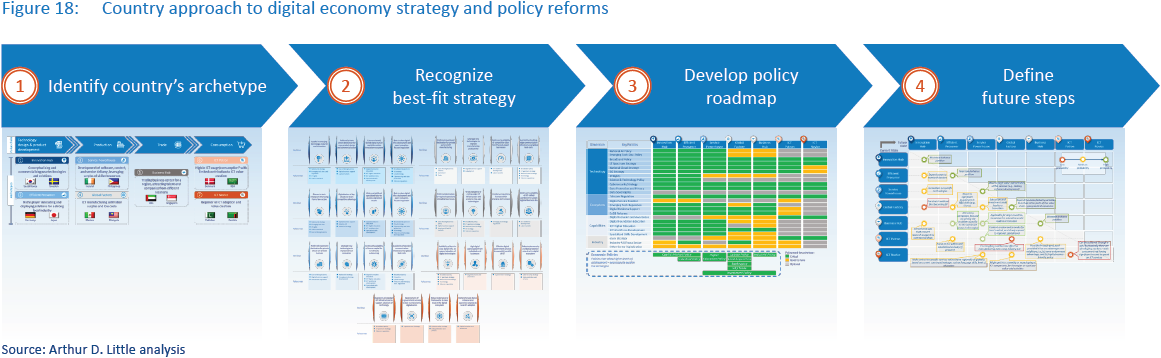

Putting policy designs into practice

Our structured archetype definition approach and integrated policy framework helps governments to identify and develop well-suited digital policies. However, it requires a coherent and comprehensive whole-of-government approach to both realize the potential of digital transformation and address its challenges.

Ultimately, the main value of any strategy lies in its successful implementation.

- Effective communication, constructive negotiation, and cooperation with all relevant stakeholders during the design phase and implementation process are crucial. For example, see the added value of cooperative regulation drafting and setting outlined by the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) in its recommendations for Fifth Generation ICT Regulatory Frameworks.

- The targeting and sequencing of measures must be well planned – for example, act first on those that are prerequisites for the success of others in order to minimize trade-offs and enable synergies between policies (OECD, 2018).

- All policy measures in the action plan that involve public spending or investment should identify the required amount and the source(s) of funding.

- Finally, a successful strategy requires a clear time frame for implementation and quantifiable targets with relevant indicators to monitor satisfactory progress.

This white paper outlines a strategic approach for developing digital economies for all countries based on their potential archetypes and recommends an overarching policy framework tailored towards each. It also provides examples of how countries have successfully transitioned across archetypes. In particular, it provides guidance for developing a digital strategy tailored to the country that reflects a whole-of-government approach to policy making in the digital age.

1

Digitalization: Aiming for growth and well-being

1.1 The digital economy today

Since the early 1990s, the definition of the digital economy has evolved based on the technology trends that characterized the times, as well as the level at which technology penetrated different tasks and markets. In the mid-1990s, “digital economy” was an abstract term associated with the emergence of the internet. Some saw it as the new networking of humans enabled by technology, and others as the convergence of computing and communication technologies that enabled e-commerce; still others defined it based on its ICT infrastructure foundations. Today, as technology rapidly evolves and becomes ubiquitous, it is widely agreed that the digital economy encompasses all those definitions. It also goes beyond the traditional ICT sector and refers to a broad range of economic activities that use digitized infrastructure and knowledge as key factors of production or value creation.

The digital economy today can be sub-divided into three categories, as shown in Figure 2:

- The core: The ICT sector, as defined by the Organization for Economic Communication and Development (OECD), is composed of manufacturing and services industries that capture, transmit and display data and information electronically. This includes semiconductors, processors, devices (computers, phones) and enabling infrastructure (internet and telecoms networks).

- Digital economy (narrow scope): The digital functions or applications that create economic value-add to business sectors and customers. This includes services and platforms (both B2C and B2B) using devices and data and connectivity infrastructure as inputs. Innovation in these sectors is widely driving spillover impacts to other sectors.

- The digitalized economy (broad scope): Sectors that were not traditionally digital are now being transformed by the adoption of digital technologies. These include, for instance, e-health, e-commerce, and use of digitally automated technologies in sectors such as manufacturing and agriculture, which include 4.0 and precision agriculture, among many others.

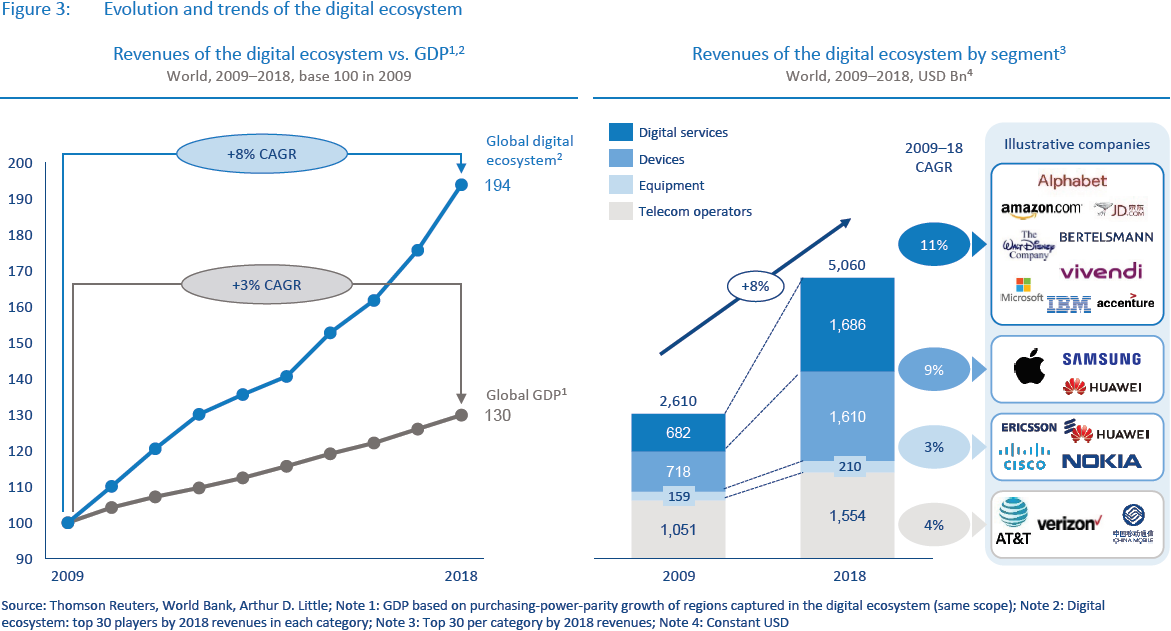

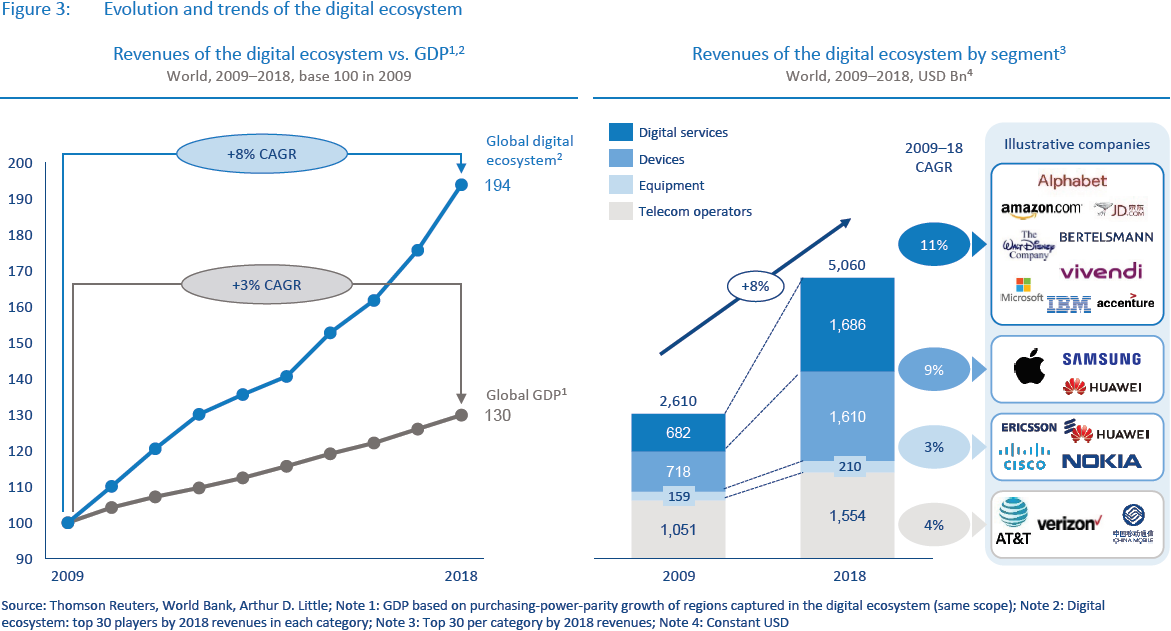

The worldwide digital ecosystem is estimated to be growing three times faster than global GDP, with digital firms leading the growth, as shown in Figure 3. While global GDP had a CAGR of 3 percent from 2009 to 2018, digital ecosystem revenues had a CAGR of 8 percent during this period. Digital ecosystem revenues, when broken down by segment, show that digital services and platform players are driving this growth (with a CAGR of 11 percent), followed by digital devices (with a CAGR of 9 percent), which showcases the increasing demand for digital services and devices globally.

Although certain components of the global digital economy are dominated by a few countries – for example, software services in Ireland and the Philippines, and hardware manufacturing in China – other parts of it are intrinsically local: e-government, e-health, support services and connectivity. Hence, large pockets of value creation and capture in the digital economy are available to all.

1.2 Digital infrastructure as a basis for transformation

High-quality and pervasive digital infrastructure is crucial to all countries. It serves to underpin the entire digital economy, forming an essential foundation for the higher layers in all value chains. Indeed, the requirement is accelerating as many economic sectors experience much-needed partial or whole digital transformations. Without high-speed and pervasive connectivity infrastructure, there can be no digitalization – for nations of any size.

As illustrated in Figure 4 digital infrastructure can be split broadly into four components: connectivity and transportation, storage and processing, digital services and applications, and terminals and devices.

Connectivity & transportation are the fundamental building blocks of digital infrastructure. All nations need international, regional, national and local connectivity infrastructure to support local activity and international connectedness. The infrastructure distribution is uneven in developed, developing and emerging markets.

Storage & processing primarily include data centers, cloud services and other data-processing services that facilitate manipulation and storage of data. Hyper-scale data centers and hyper-converged storage are likely to become indispensable with the ongoing and future expected data explosion.

Digital services and applications encompass functions and applications that create economic value-add to business sectors and customers. This is the fastest-growing segment, and various industries are disrupted by digital technologies.

Terminals and devices serve as interfaces between digital users, including both individuals and machines. Penetration of human-operated devices is moving towards saturation, especially in developed countries. Human augmentation is gaining prominence in devices.

Key challenges across all components of digital infrastructure development are security, funding and adoption. In addition:

- The primary challenge for connectivity infrastructure continues to be lack of clarity on funding and regulations, especially for reducing the digital divide as return on investments remain low in sparsely populated, rural areas.

- Breaches of cybersecurity, privacy and data sovereignty are key challenges for storage and processing infrastructure.

- Digital literacy and skills remain a key barrier for digital services.

- Fragmented M2M technical standards and low affordability are stifling growth of terminals and devices.

Policy makers globally should acknowledge these challenges and address them to promote next-generation digital infrastructure development and enable their digital economies to grow.

1.3 Stakes are high: Economic and social impact

Digital transformation can result in long-lasting benefits for economies because digital technologies drive innovation, fuel high-paying job opportunities and spur economic growth. Depending on the definition, estimates of the size of the digital economy today range from 4.5 to 15.5 percent of world GDP. When defined as a distinct economic sector on the narrowest of definitions, it would still rank among the top 10 economic sectors globally.

The digital economy, per the broadest of definitions, is estimated to be $11.5 trillion, or 15.5 percent of world GDP – 18.4 percent of GDP in developed economies and 10 percent in developing economies, on average.

The transition to a digital economy will also boost national competitiveness across all sectors and bring about myriad new opportunities for businesses. It can also provide new tools and facilitate knowledge transfers for tackling persistent development and social issues.

To reap such benefits, countries need to overcome several challenges, which may vary with levels of economic development.

Developed nations are less constrained, as most have adequate ICT infrastructure foundations in place. However, they face the challenge of aging populations, which limit their economically active bases and pose a risk to digital consumption. In most countries, seniors remain largely disconnected from the digital revolution.

On the other hand, developing countries face larger constraints to grow their digital economies. Firstly, they lag in digital infrastructure availability, which translates into lower levels of internet usage across these nations. In least-developed countries (LDCs), only one in five people uses the internet, compared with four out of five in developed countries. Further challenges arise from a wide gap in digital capabilities and awareness compared to those of developed nations. Developing nations need to carefully recognize their digital landscapes and select policy actions that will maximize the benefits of digitalization, given their limited resources.

If developed countries succeed at adopting digital technologies, they will become more competitive and maintain their global influence. For developing countries, the prize is even more significant, as digitalization could support an economic leapfrog.

Impact of digital infrastructure investments

The positive economic impact of mobile and fixed broadband has been widely studied and acknowledged. In 2019, using a cross-sectional time-series analysis, ITU explored the economic impact of broadband in LDCs, LLDCs and SIDSs for the period 2000–2017. Its findings confirm that mobile broadband appears to exert a slightly stronger impact than fixed broadband, generating a 2.5–2.8 percent increase in GDP per capita per 10 percent increase in penetration, compared to a 2.0–2.3 percent increase for fixed broadband. In developed and developing countries, a 10 percent increase in fixed broadband penetration generated a 0.8 percent increase in GDP. A 10 percent increase in mobile broadband penetration generated a 1.5 percent increase in GDP.

Another ITU study showed that the economic impact of digitization was even higher than that from fixed broadband diffusion and similar to that of mobile broadband. The positive impacts of digitization were found to be even higher in more advanced countries. According to this study, an increase of 1 percent in the digital ecosystem development index (used as a proxy measure for the extent of digital transformation in a country) equated to an additional 0.13 percent growth in GDP per capita. An increase of 1 percent in the digital ecosystem development index yields an increase of an additional 0.14 percent in per capita GDP for OECD countries, while the impact of a similar change in non-OECD countries was 0.10 percent. The same study also indicated that an increase in the digital ecosystem development index of 1 percent yielded an increase of 0.26 percent in labor productivity, and 0.23 percent in total factor productivity.

While the impact of legacy technologies has been extensively reviewed, the economic impact of emerging technologies remains largely unquantified, with the exception of a few studies published on specific technologies. For example, 5G is expected to influence two billion new users to come online worldwide and result in $2 trillion to $4 trillion cumulative real GDP boost by 2030. At 70% adoption rate, AI is estimated to contribute $13 trillion (cumulatively from 2020) to global GDP by 2030. One Gartner study estimated that the business value-add of blockchain will be $3.1 trillion by 2030.

In another study by Oxford Economics and Huawei, a new approach to measuring the digital economy was developed, which captures the value of digital spillovers. As per this study, in a high-digitalization scenario, the global digital economy could grow to account for 24.3 percent of global GDP by 2025, which equates to $23 trillion. This scenario assumes all 50 economies in the study can maintain an aggressive pace of digital investment and work together to deliver a strong digital strategy, including a supportive infrastructure, a thriving entrepreneurial class and a vibrant technology sector.

Impact of digitalization on industry, consumer and society

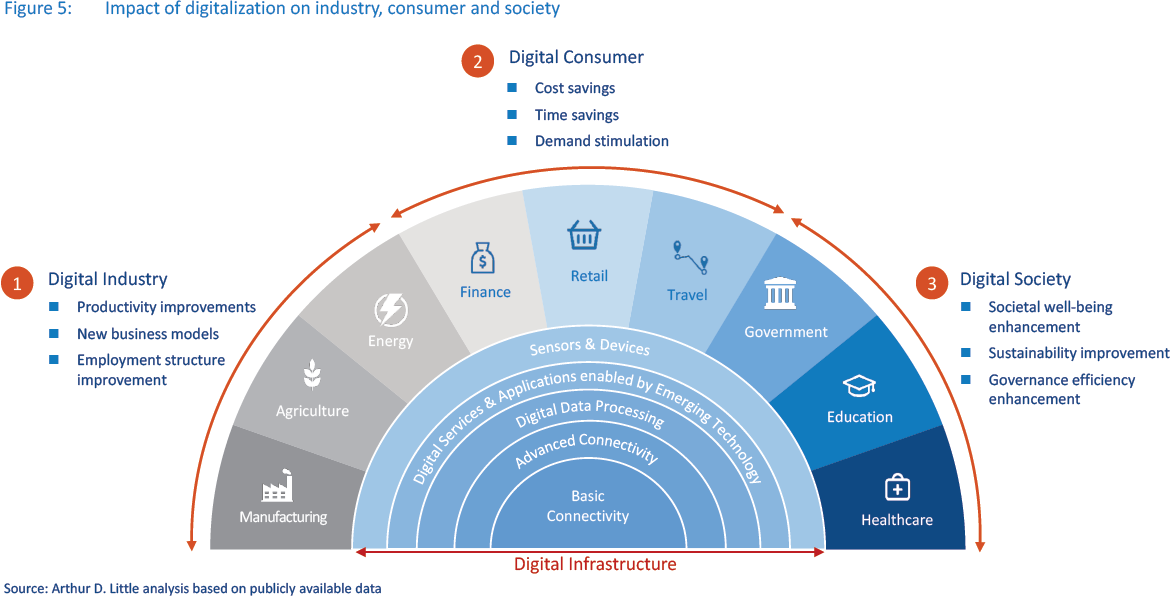

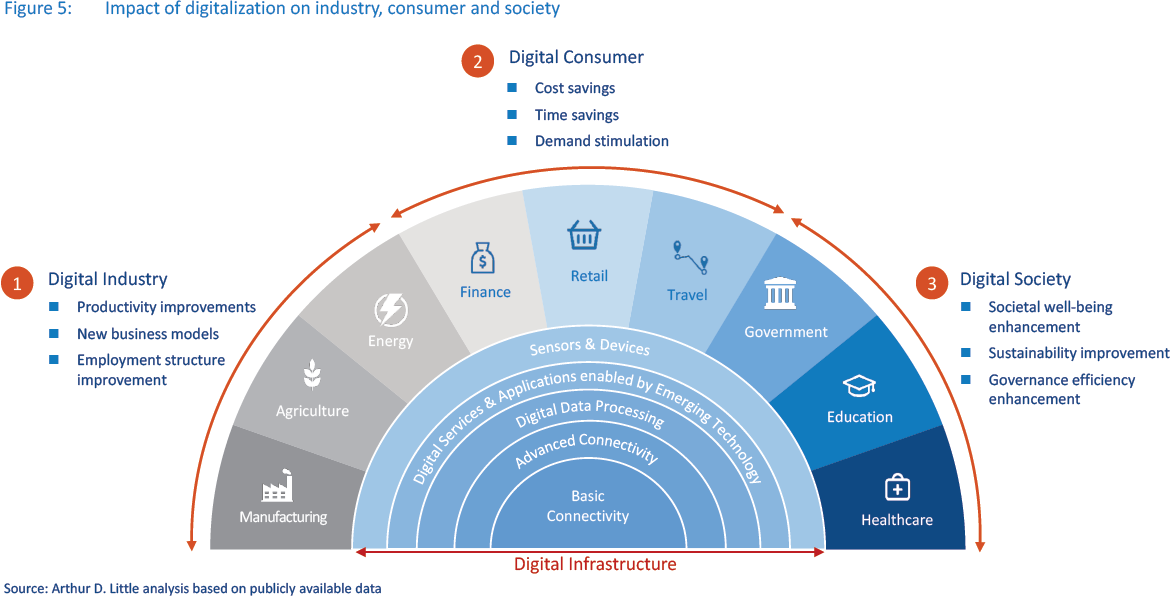

The potential impact of digitalization is maximized when digital infrastructure is leveraged by industry, consumers and society at large. We have classified digitalized economic sectors into these three broad groups, as observed in Figure 5.

- Digital industry

Traditional sectors such as agriculture, manufacturing and energy are facing disruptive challenges from declining prices for many commodities, lack of skilled and unskilled labor, and alternative markets. However, with the proliferation of the IoT and other digital technologies, there is significant potential to improve productivity.

The individual economic impact for each sector will differ by country, but it will be significant for nations that strongly depend on these sectors. For instance, smart manufacturing is expected to generate productivity gains of between 15 and 25 percent. In Germany, this translates to €153 billion of additional growth created by 202018 and an expected rise in employment of 6 percent between 2015 and 2025. In Germany, for example, the government has established central Platform 4.0, which includes an overall governance team, a research council, a standardization council and an Industry 4.0 labs network – it also undertook extensive efforts to retain the dominance and competitiveness of the manufacturing sector. Germany is enabling Industry 4.0 by ensuring that the appropriate technology, capabilities and ecosystem are in place and well-coordinated among all stakeholders.

Similarly, the adoption of digital technologies in agriculture is enabling the development of precision farming, enhanced livestock monitoring, and other use cases. Furthermore, the digitalization of the energy and utilities sector enables improved energy management, more precise extraction of raw materials and remote management of energy assets, which improves safety. Digital transformation in this sector is forecasted to save up to $750 billion globally by 2025.

- Digital consumer

Consumer-oriented sectors such as retail, finance and travel are also rapidly digitalizing. Digitalization helps to cope with pressing consumer trends such as product personalization and rapid delivery, higher demand for product traceability, and increased cost and time sensitivity for travel. It enables a reduction in end-product costs, enhances the shopping experience, increases financial inclusion, improves travel efficiencies and has a positive impact on the environment.

In the retail sector, for instance, technology use cases range from mature e-commerce activities, to customer analytics, to emerging virtual-store experiences. The use of simulation and virtual reality in the last use case will allow customers to engage fully with their products before even purchasing them. For products such as cars, sports gear, and other experience-oriented goods, such enhanced retail opportunities will be a large differentiating factor. For some markets, such as China, B2C e-commerce contributed around 2 percent of total GDP in 2018.

The government of China played a key role in implementing regulations and policies to support the e-commerce sector in three stages to support its rapid development. In the first stage – Initiation & Acceleration (2000–2008) – basic digital infrastructure was deployed, new regulations for e-commerce were formulated and rolled out, and an e-commerce five-year plan was developed. In the second stage – Standardization (2008–2014) – a national policy management system for the e-commerce industry and standards were formed, and the first enterprises were granted permission for online payment transactions. In the third stage – Globalization (2014–2019) – detailed cross-border e-commerce development strategies and international cooperation policies were put in place, and other policies were undertaken, including making it easier to build e-commerce infrastructure (e.g., logistics hubs), financial incentives, and initiatives to strengthen the credibility of payment systems and enhance e-commerce security. All this led to China’s e-commerce sector becoming a large economic contributor, supporting 34 million direct and indirect jobs in total in 2019.

Likewise, the digitalization of financial services has enabled e-payments that complement various sectors and increased accessibility to financial markets. It has also facilitated enhanced security by utilizing blockchain to trace transactions, big data and analytics to detect fraud, and the IoT to develop tailored insurance policies. By 2025, the digitalized financial sector is expected to generate between $0.6 trillion and $0.8 trillion in total revenues globally and create around 95 million jobs in the developing world.

In transportation, digitalization is enabling dynamic systems that help reduce traffic and pollution, integrated platforms that enhance the travel experience and reduce travel times, and smoother logistics through the use of blockchain and digital twins. More advanced technologies are expected to have a significant impact. Most of the value would arise from reducing the toll of vehicle crashes, as well as from giving productive time back to commuters, improving energy security by reducing dependence on oil, and providing environmental benefits.

- Digital society

Sectors focused on benefiting society as whole, such as healthcare, education and government, are utilizing digital technologies to improve access to high-quality services, progress urban management, enhance government transparency, and enable a more secure country ecosystem. Furthermore, countries that are highly advanced in embracing digital society solutions have introduced a holistic approach that aims to provide citizens with a fully digital experience.

Having 94 percent of the population digitally engaged in both online public and private services, Denmark is well on its way towards a digital society. The Danish government has made a commitment to go “digital by default” and most transactions are cashless, and almost all interaction with the Danish authorities takes place online. Its e-government projects, such as NemID, have already yielded positive responses from the citizens, with 88 percent of the population actively engaged with digital public authorities.

The economic impact of digitalizing individual societyfocused sectors is smaller than its two counterparts, as most of the benefits are quality-of-life improvements rather than economic-output generation. Government digitalization enables countries to do traditional public processes in a more agile manner, recognize threats more effectively, and increase access to public services for communities that might not be well served. Revenues from the digitalization of government are expected to reach $655 billion globally by 2025 and generate up to 70 percent in cost savings. Similarly, digitalizing healthcare has tremendous potential for society as it helps increase access to such services, tailors more effective treatments, prevents diseases, and enhances the precision of health interventions such as operations. Revenues for this sector may reach around $500 billion by 2025 and reduce consultation costs by up to 30 percent. Finally, in the education sector, students can access more engaging and creative experiences using smart boards and gamification approaches. Virtual classrooms are also becoming predominant and could be transformed into engaging, immersive 3D experiences that could replicate environments such as laboratories. In addition, digital technologies may serve a better purpose, to tailor education to students’ needs rather using a “one size fits all” approach, which would enhance academic attainment and reduce dropouts. However, it is crucial for policy makers to ensure equitable access to digital infrastructure, otherwise welfare gaps could be exacerbated.

Overall, the net impact of digitalization in nations will depend on the level of development and digital readiness of each country and its stakeholders. It will also depend on the policies adopted and implemented at national, regional and international levels. Most importantly, to maximize the benefits of digitalization, policy makers will need to ensure that their digital policies are crafted to meet specific country challenges.

2

Digital economy models for all

2.1 Defining archetypes

There is a universal acceptance of the need for economies to digitalize, but countries face dilemmas in allocating scarce resources and finite funds. The challenge emanates from the inability to define focus areas for the growth of the digital economy, as successful digital economies require a whole range of infrastructure and capabilities.

The question for policy makers is, what does it take to use ICT to transform an economy? Why do some countries rapidly accelerate their development journeys using ICT, while others fail? How do successful countries balance strategic leadership and bottom-up innovation? What should the roles of government and the private sector be?

The key questions are: “Which recipe best fits my current situation, and builds towards my ambition?”

“What should I have in common with others, and where should I differentiate?”

Most importantly: “Why?”

When considering different policy options and practices aimed at maximizing benefits from the digital economy, policy makers need to recognize that “one size does not fit all”. They need to make careful and deliberate choices on how their nations take part in the new digital world – not just as users and consumers, but also as producers, exporters, innovators, and regulators – to create and capture more value on their paths towards sustainable development. With the objective of supporting policy makers in their thinking processes, we have identified different digital economy archetypes and developed an aspirational digital strategy for each. This tailored digital strategy will guide policy priorities.

Our approach begins with the recognition and definition of archetypes. An archetype serves as a reference model that countries can adapt based on their current situations.

Using an archetype framework for assessing opportunities and challenges, and then analyzing the options for development of ICT strategies, goes beyond a static assessment of the ICT industry. It looks at a typical long list of recommendations for transforming the ICT sector in a country. It allows a country to make necessary choices and trade-offs when designing and implementing ICT strategy within human, financial and institutional constraints. It considers initial conditions, stakeholder interest, institutional dynamics and political willingness. Rather than looking at the causality of individual elements of the digital infrastructure, such as connectivity, ICT skills, e-government initiatives and development objectives, an archetype approach allows these elements to be strategically linked.

An archetype approach allows the country to link ICT strategy to national development strategies, which leads to an “interaction effect” – interaction between ICT investment, infrastructure, skill levels and policy environment. Reaching a minimum threshold allows the country to benefit sufficiently from returns to scale and investment in digital infrastructure. The different archetypes demonstrate the manner in which countries have captured and managed various interdependencies over time. This approach allows policy makers to define the interdependence between actions and resources of different stakeholders, the linkages between various stakeholders, and the roles of various stakeholders and their interactions.

Our analysis of the ICT value chain includes detailed benchmarking of beneficial policies and capabilities in 15 countries, discussions with experts in national digital transformation and the ICT market, and a literature review – it also leverages Arthur D. Little’s project repository of national ICT strategies and industry experience. Through this, we have identified seven digital economy archetypes, as show in Figure 6. Archetypes differ in their positions across the ICT value-chain steps, and thus the value they capture from the ICT industry. However, archetypes are not limited to specific steps in the value chain, but rather, their positions mark focal domains in the overall value chain. They can be further differentiated through other underlying characteristics, such as economic status, population size, political stability, geographical advantage and technology penetration. Through specific combinations of these elements, we have distinguished seven archetypes.

Countries in this archetype capture the highest value from the ICT industry. They are leaders in conceptualizing and developing new technologies and commercializing innovative solutions based on them. They are home to global digital giants and can foster technology-enabled start-ups, and consequently capture large shares of the digital economy. For instance, countries that are advanced in developing AI applications or introducing IoT-enabled platforms, such as South Korea match this archetype. The advancement of technology innovation is based on a robust ecosystem that promotes basic and applied research and technology development across the public, private and academic sectors. Becoming an Innovation Hub requires significant investments, a long-standing base of knowledge, and extremely high levels of technical capabilities, which are usually built over decades. The archetype’s primary focus is not to produce technology for its own consumption, but rather, to be the leader in cutting-edge innovation and create worldwide demand for its products.

Countries in this archetype capture the highest value from the ICT industry. They are leaders in conceptualizing and developing new technologies and commercializing innovative solutions based on them. They are home to global digital giants and can foster technology-enabled start-ups, and consequently capture large shares of the digital economy. For instance, countries that are advanced in developing AI applications or introducing IoT-enabled platforms, such as South Korea match this archetype. The advancement of technology innovation is based on a robust ecosystem that promotes basic and applied research and technology development across the public, private and academic sectors. Becoming an Innovation Hub requires significant investments, a long-standing base of knowledge, and extremely high levels of technical capabilities, which are usually built over decades. The archetype’s primary focus is not to produce technology for its own consumption, but rather, to be the leader in cutting-edge innovation and create worldwide demand for its products.

Countries in this archetype are niche players that innovate and deploy solutions for dominant local industries. They focus on the same step of the ICT value chain as Innovation Hubs: technology design and product development. They also have strong ecosystems that promote research and development (R&D) activities around emerging technologies. The key differentiating characteristic is that Efficient Prosumers focus their efforts on developing technology solutions that will enhance the competitiveness of a single or a few economic sectors within their countries. The digitalization effort in the core industries leads to spin-off benefits in other industries. An example is Germany, which has heavily invested in digitalizing manufacturing, including the automotive and machine-building sectors, and pursuing Industry 4.0 at large. In the past, digitalization of the manufacturing sector in Germany led to SAP becoming a leading player in the enterprise resource planning software domain.

Countries in this archetype are niche players that innovate and deploy solutions for dominant local industries. They focus on the same step of the ICT value chain as Innovation Hubs: technology design and product development. They also have strong ecosystems that promote research and development (R&D) activities around emerging technologies. The key differentiating characteristic is that Efficient Prosumers focus their efforts on developing technology solutions that will enhance the competitiveness of a single or a few economic sectors within their countries. The digitalization effort in the core industries leads to spin-off benefits in other industries. An example is Germany, which has heavily invested in digitalizing manufacturing, including the automotive and machine-building sectors, and pursuing Industry 4.0 at large. In the past, digitalization of the manufacturing sector in Germany led to SAP becoming a leading player in the enterprise resource planning software domain.

Countries in this archetype are recognized for their formidable positions in the global supply of ICT services. Their competitive advantage in this sector is the result of large, active populations that were effectively translated into surpluses of ICT workers, which resulted in low costs for delivering such activities. Nonetheless, countries without such advantages must not be discouraged, as other skills, such as strong international language proficiencies, have also proven to increase the opportunity for countries to become key players in the ICT services market. The Philippines, for example, became one of the largest ICT service outsourcing markets in the world, given its large, economically active population with a good command of English, as it is the language of instruction in schools. Service Powerhouses are not generally high-income countries. Their technology innovation efforts are relatively low compared to the two previously mentioned archetypes and are limited to processes involved in creating and delivering ICT services.

Countries in this archetype are recognized for their formidable positions in the global supply of ICT services. Their competitive advantage in this sector is the result of large, active populations that were effectively translated into surpluses of ICT workers, which resulted in low costs for delivering such activities. Nonetheless, countries without such advantages must not be discouraged, as other skills, such as strong international language proficiencies, have also proven to increase the opportunity for countries to become key players in the ICT services market. The Philippines, for example, became one of the largest ICT service outsourcing markets in the world, given its large, economically active population with a good command of English, as it is the language of instruction in schools. Service Powerhouses are not generally high-income countries. Their technology innovation efforts are relatively low compared to the two previously mentioned archetypes and are limited to processes involved in creating and delivering ICT services.

Countries in this archetype lead in ICT manufacturing and also have large surpluses of labor force. However, compared to Service Powerhouses, a workforce with an adequate level of ICT skills is less critical. The large, economically active populations tend to be employed in manufacturing activities, with ICT goods constituting a large proportion of production. Low costs of labor tend to enhance the competitiveness of ICT goods prices, allowing countries in this archetype to be large global exporters. Mexico and Malaysia are representative members of the Global Factory archetype; ICT goods exports accounted for >15 percent of total goods exports for both in 2017. To retain this advantage, countries tend to focus on complementary investment in physical infrastructure that enhances the competitiveness of exports such as factory clusters, trade warehouses and logistics hubs. Technology innovation efforts are relatively low & tend to be limited to production processes & tools.

Countries in this archetype lead in ICT manufacturing and also have large surpluses of labor force. However, compared to Service Powerhouses, a workforce with an adequate level of ICT skills is less critical. The large, economically active populations tend to be employed in manufacturing activities, with ICT goods constituting a large proportion of production. Low costs of labor tend to enhance the competitiveness of ICT goods prices, allowing countries in this archetype to be large global exporters. Mexico and Malaysia are representative members of the Global Factory archetype; ICT goods exports accounted for >15 percent of total goods exports for both in 2017. To retain this advantage, countries tend to focus on complementary investment in physical infrastructure that enhances the competitiveness of exports such as factory clusters, trade warehouses and logistics hubs. Technology innovation efforts are relatively low & tend to be limited to production processes & tools.

Countries in this archetype are characterized by the presence of advanced & conducive business environments when compared to their regional counterparts. They tend to be the preferred locations for international firms to set up their regional headquarters or key operations offices. They attracted businesses owing to their flexible and conducive business regulations, availability of state-of-the-art infrastructure, attractive standards of living, and strategic connectivity to various markets in comparison to other countries within their regions. Examples include the United Arab Emirates and Turkey. Beyond a conducive business ecosystem, Business Hubs are also politically stable and provide favorable terms of trade for both producers and consumers of ICT goods and services. Consequently, Business Hubs’ biggest contributions to the ICT value chain is to serve as trading platforms for ICT products that are to be distributed to nearby countries.

Countries in this archetype are characterized by the presence of advanced & conducive business environments when compared to their regional counterparts. They tend to be the preferred locations for international firms to set up their regional headquarters or key operations offices. They attracted businesses owing to their flexible and conducive business regulations, availability of state-of-the-art infrastructure, attractive standards of living, and strategic connectivity to various markets in comparison to other countries within their regions. Examples include the United Arab Emirates and Turkey. Beyond a conducive business ecosystem, Business Hubs are also politically stable and provide favorable terms of trade for both producers and consumers of ICT goods and services. Consequently, Business Hubs’ biggest contributions to the ICT value chain is to serve as trading platforms for ICT products that are to be distributed to nearby countries.

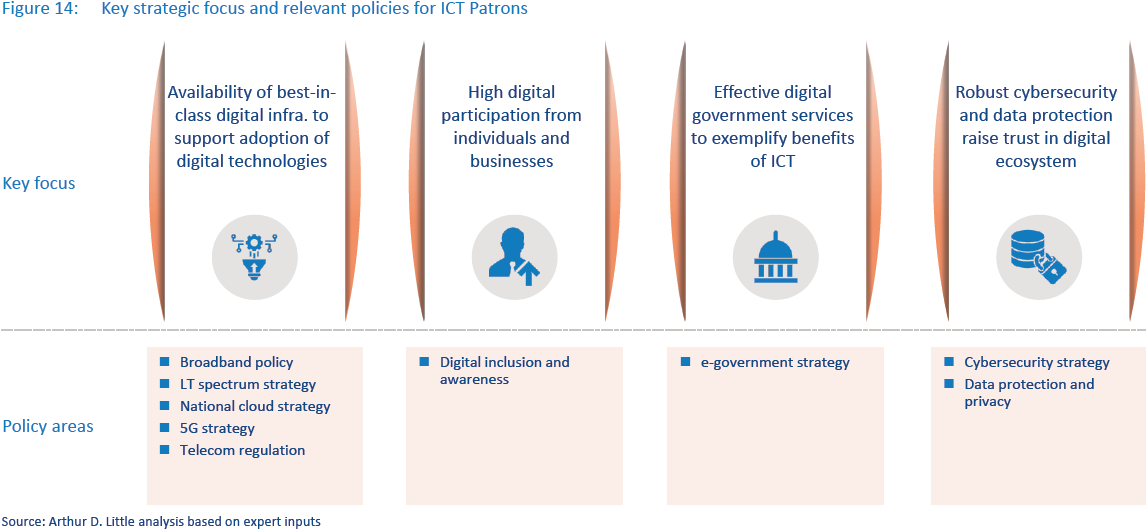

Countries in this archetype are known for their large-scale consumption of ICT goods and services, but their contribution to the global ICT value chain is low. Their large demand for technology solutions is rooted in the prevalence of high-income societies and robust basic ICT infrastructure such as high-speed internet and large international bandwidth. However, most of their consumption is satisfied through imports. Examples of these countries include Saudi Arabia, with ICT consumption rising annually, and Denmark as the world leader in e-government as per the UN E-Government Survey 2018. ICT Patrons tend to be differentiated from Business Hubs by the fact that they are not as attractive for international companies to set up their key offices, and thus do not feature large volumes of trade beyond the imports needed to satisfy local demand.

Countries in this archetype are known for their large-scale consumption of ICT goods and services, but their contribution to the global ICT value chain is low. Their large demand for technology solutions is rooted in the prevalence of high-income societies and robust basic ICT infrastructure such as high-speed internet and large international bandwidth. However, most of their consumption is satisfied through imports. Examples of these countries include Saudi Arabia, with ICT consumption rising annually, and Denmark as the world leader in e-government as per the UN E-Government Survey 2018. ICT Patrons tend to be differentiated from Business Hubs by the fact that they are not as attractive for international companies to set up their key offices, and thus do not feature large volumes of trade beyond the imports needed to satisfy local demand.

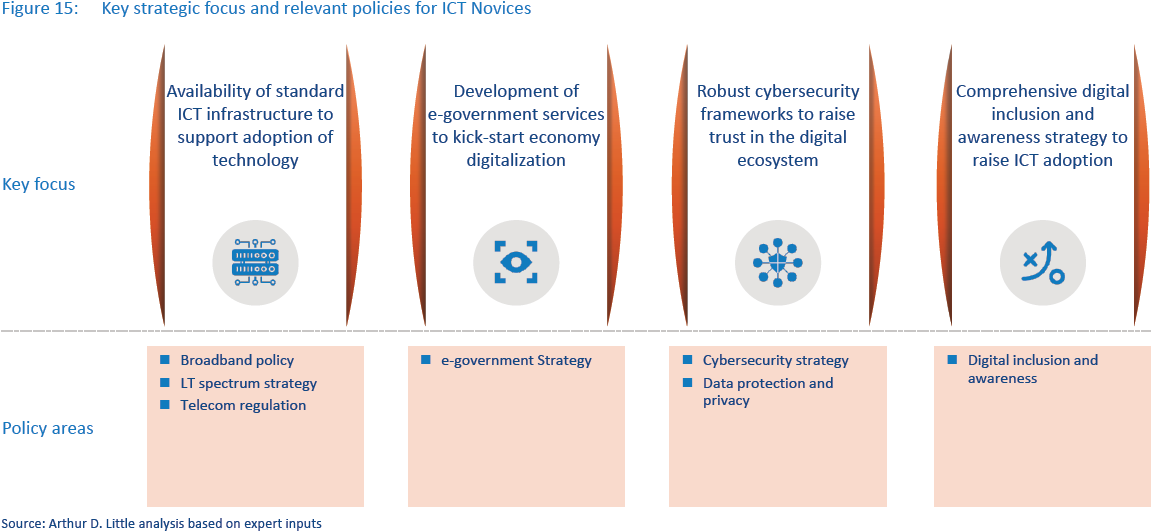

The last of our archetypes is constituted by countries with the least contributions to the ICT value chain. Usually these countries have limited economic resources and low levels of educational attainment and may suffer from geopolitical instability. Based on this context, ICT Novices have not prioritized ICT infrastructure investments historically, as their limited economic resources have been allocated to more pressing needs. Therefore, they tend to fall behind in internet penetration and ICT skills across their populations. This translates into low demand for ICT solutions, which is met either by low-tech innovative local players or through imports, depending on specific needs, and most importantly, the lowest prices available. Most of these countries will have only recently become aware of the benefits that could arise from digitalization. Therefore, they will have started drafting their digital economy strategies and thinking about the best ways to close the gap with countries already advanced on the digital transformation quest.

The last of our archetypes is constituted by countries with the least contributions to the ICT value chain. Usually these countries have limited economic resources and low levels of educational attainment and may suffer from geopolitical instability. Based on this context, ICT Novices have not prioritized ICT infrastructure investments historically, as their limited economic resources have been allocated to more pressing needs. Therefore, they tend to fall behind in internet penetration and ICT skills across their populations. This translates into low demand for ICT solutions, which is met either by low-tech innovative local players or through imports, depending on specific needs, and most importantly, the lowest prices available. Most of these countries will have only recently become aware of the benefits that could arise from digitalization. Therefore, they will have started drafting their digital economy strategies and thinking about the best ways to close the gap with countries already advanced on the digital transformation quest.

The archetypes have distinct presence across ICT value-chain steps and distinct comparative advantages derived from their endowments, such as economic status, population size, political stability, geographical advantage or abilities gained over decades due to legacy policy choices. Except for ICT Novices, the archetypes typically have politically stable environments and are not very low-income economies.

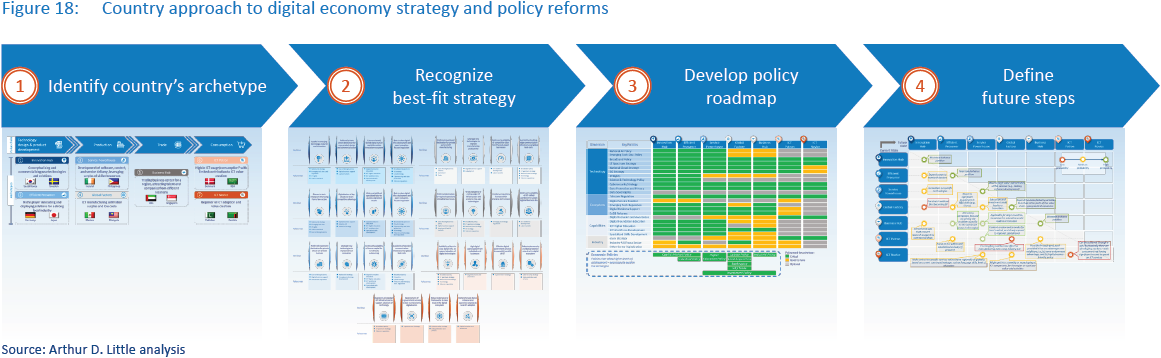

The archetype approach supports policy makers in their thinking processes and helps articulate the countries’ strengths, core capabilities, and unique differentiators. Recognition of each country’s archetype is the critical first step towards developing a tailored digital strategy that will guide policy priorities.

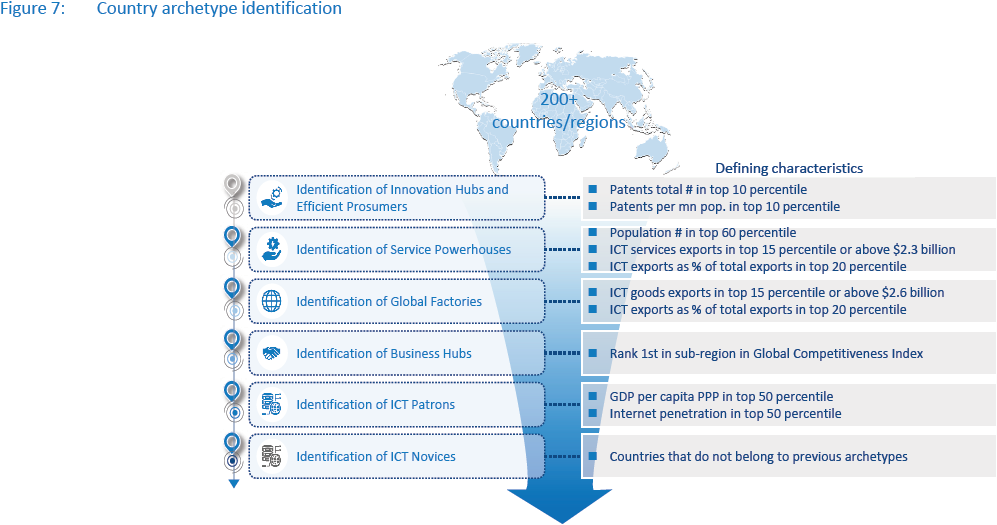

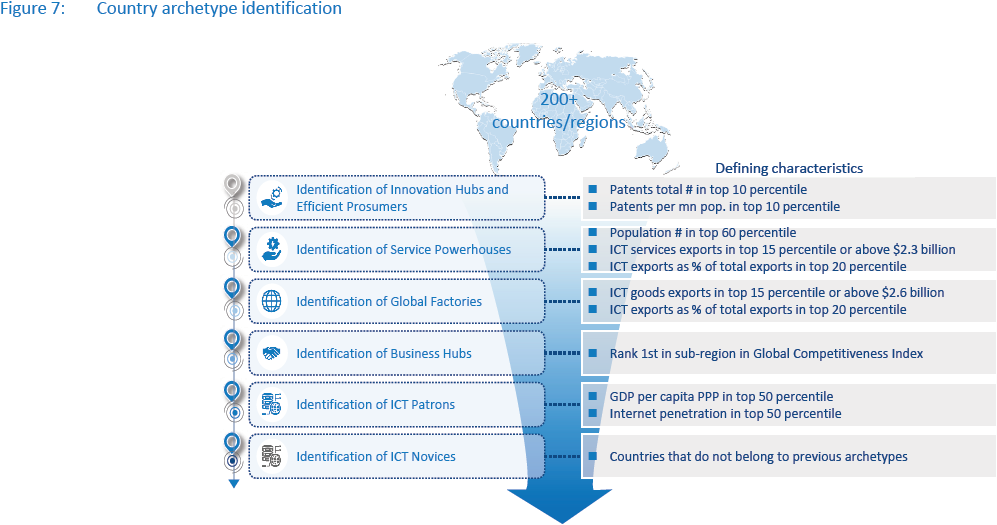

2.2 Mapping the world

We identified 200+ countries’/regions archetypes based on their defining characteristics. This is illustrated in Figure 7, which showcases a sample of 28 of these countries/regions and archetypes. Multiple defining characteristics were used to identify the countries’/regions archetypes, including the rate of innovation, importance of the ICT sector in terms of services and goods, international competitiveness, economic development, and degree of internet connectivity. Each of these characteristics was proxied by a quantifiable indicator, including (in the same order) number of patents, ICT goods exports, ICT services exports, competitiveness ranking as per the WEF’s global competitiveness index, GDP per capita (PPP), and internet penetration.

The analysis resulted in two key insights:

- Archetypes are not mutually exclusive, and countries/ regions can also present the characteristics of a secondary archetype. Out of our sample of 204 countries/regions, we found that around 14 percent had secondary archetypes. For instance, China’s primary archetype is recognized to be Innovation Hub; however, given it belongs to the top 10 percent of countries in terms of ICT goods exports as a percentage of GDP, as well as total value, it also presents the characteristics of a Global Factory. A similar trend is observed for Malaysia, whose primary archetype is Global Factory; nevertheless, the country also presents salient characteristics of a Service Powerhouse, scoring in the top 15 percent of countries in terms of ICT services total value.

- Transition to a higher-value-adding archetype is possible and even desirable but requires a concerted effort. For example, China transitioned from Global Factory to Innovation Hub, and Mexico from ICT Novice to Global Factory.

3

Tailoring digital strategy and public policy

3.1 Succeeding within the archetype

The kind of digital future that a country aims for will be central to the success of the country’s digital economy. We believe that selecting the best strategic path should be based on the characteristics of the country’s archetype. Policy makers may need to adapt existing policies, laws and regulations, and/or craft new ones to ensure consistency with their desired digital futures.

That being said, the digital economy calls for unconventional thinking and policy analysis. The archetype framework provides the opportunity to recognize variations of digital economy strategies that require different policy-domain combinations across digital economy dimensions. This does not mean countries should disregard other policies, but instead, ensure that policies critical for their archetypes are given due resources, budget and attention.

The final list of policy areas was built by thoroughly studying existing policies in countries with different levels of economic, social, geo-political and technological development. This was further enhanced through a literature review of digital economy policy papers from leading international organizations. Detailed analysis of digital policies, highlighting best-practice policy components, can be found in the Appendix document. In Figure 8, we have outlined the policy list, grouped as per the digital economy pillars, and mapped their criticality for each archetype.

Throughout the remainder of this section, we will provide synopses of how different archetypes may follow varying policy strategies, as described in chapter 2. It includes:

- An overview of the digital economy strategy of the archetype and key focus areas/strategic objectives.

- The policy domains that are most critical for each focus area.

Countries may use these narratives as starting points to reflect on how they wish to shape their unique digitalization paths. However, when designing digital economy strategies, it is crucial for individual countries to go one level deeper and understand their specific performances across digital economy enablers, as the archetype is merely a tool to structure and stimulate thinking, rather than the basis of a fixed model. The stories below include examples and short case studies of approaches taken by countries to help ground the theory.

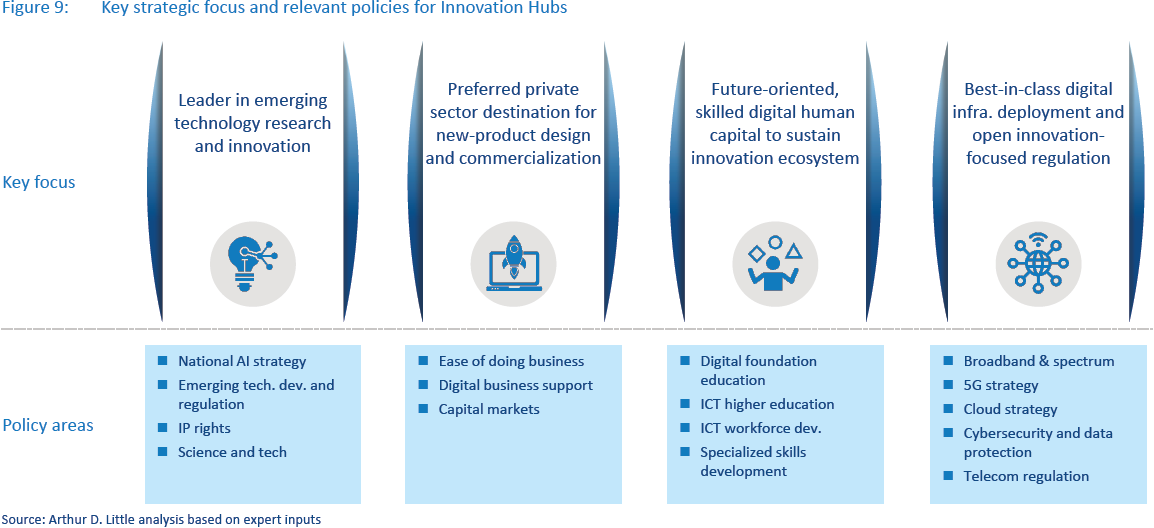

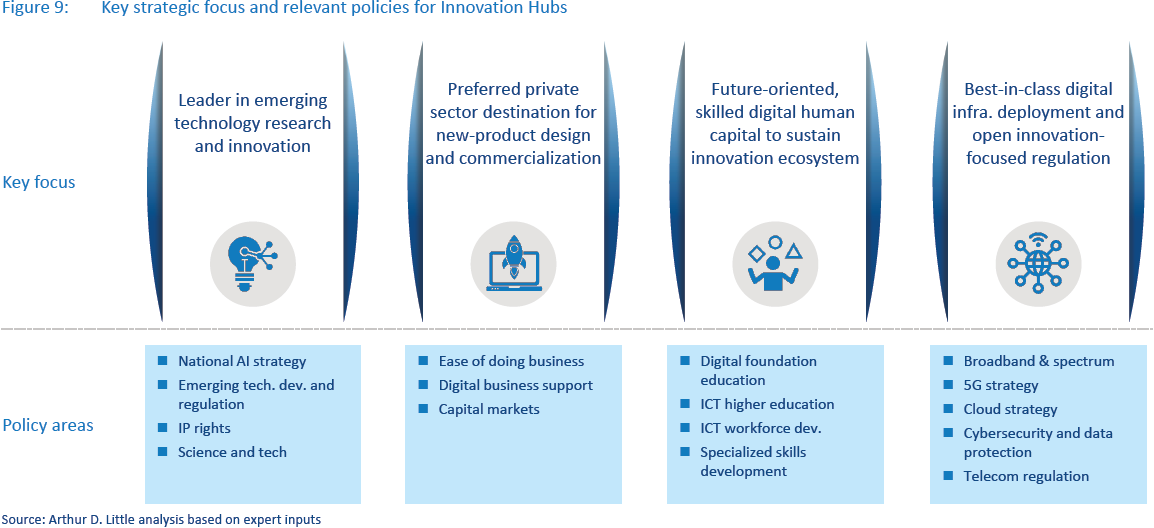

3.1.1 Innovation Hub

As implied by its archetype title, the overall digital economy strategy of an Innovation Hub is to maintain its leading position as “the location” for innovation. Consequently, the key strategic objectives of an Innovation Hub are to:

- Become a leader in emerging technology research and innovation.

- Be the preferred private sector destination for new product design and commercialization.

- Build future-oriented, skilled digital human capital to sustain the innovation ecosystem.

- Deploy best-in-class digital infrastructure and open innovation-focused regulation.

Each of these strategic objectives can be strengthened through efforts across various policy domains.

Leader in emerging technology research and innovation

To be a pioneer in emerging technology innovations, large-scale public and private sector funding in science and technology research is critical. To drive R&D, policy makers can offer direct or indirect financial support to public agencies, academic institutions or private sector players engaging in such activities. Although countries should consider pursuing a mix of both measures, direct funding offers governments the opportunity to steer the focus of R&D efforts into key areas with the most added-value potential for the country. Israel is an example of a leading country in R&D; its expenditure reached 4.2 percent of its GDP, and it hosts 320 R&D centers across the country, operated by leading international companies such as Apple, Google, Intel, Microsoft, HP, IBM and eBay. Israel built an attractive environment for R&D by setting up financial incentives, ensuring an adequate supply of specialized workforce, and encouraging cooperation between public, private and academic stakeholders. Innovation Hubs should also have comprehensive AI and emerging technology development policies aimed at encouraging innovation and fostering business investments and technology commercialization, while managing issues around regulation, ethics and privacy to protect citizens and society. Robust IP-rights protection is paramount to promote private sector participation in R&D in the country.

Preferred private sector destination for new product design and commercialization

To convert research into commercial products, larger private sector involvement is critical. Policy instruments to achieve such goals include digital business funding support such as publicprivate funding schemes with existing incubators or business accelerators and setting up government-backed venture capital (VC) programs to convert research into commercial products. In the UK, 41 percent of existing business accelerators received public funding, with a key focus in space and satellite technology development, agriculture-tech and transport. Policies to enable EoDB and those that facilitate access to capital markets are critical to attract the private sector and foster an innovation ecosystem.

Future-oriented, skilled digital human capital to an sustain innovation ecosystem

To sustain the advancement of their technology innovation ecosystems, Innovation Hubs should retain and attract the best talent in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). Achieving such goals requires transformation of the entire education system of a country. At the foundational education level, it entails developing students’ creativity, critical thinking, entrepreneurship and communication skills, as well as reinforcing their abilities in STEM subjects and engaging them with technology usage from young ages. At the tertiary education level, governments need to increase interest in careers that will support the evolving ICT and innovation ecosystem. This may be realized through scholarships, subsidized research programs, international exchanges, academic challenges and labor-office support offered to students pursuing such careers.

Best-in-class digital infrastructure and open innovationfocused regulation

To sustain the innovation ecosystem, Innovation Hubs should deploy best-in-class digital infrastructure, as well as set up conducive regulatory ecosystems that support emerging technology use-case development. Policy makers need to promote the growth of next-generation mobile technologies (5G), as these have the potential to stimulate innovation, support digitalization of various economic sectors, and help meet the increasing demands of the digital economy. Policy makers should consider streamlining rights of way, managing spectrum efficiently, enhancing deployment and access to fiber backhaul, and updating infrastructure-sharing regulations. In addition, they should follow adaptive regulation regimes for emerging technologies, taking responsive and iterative approaches.

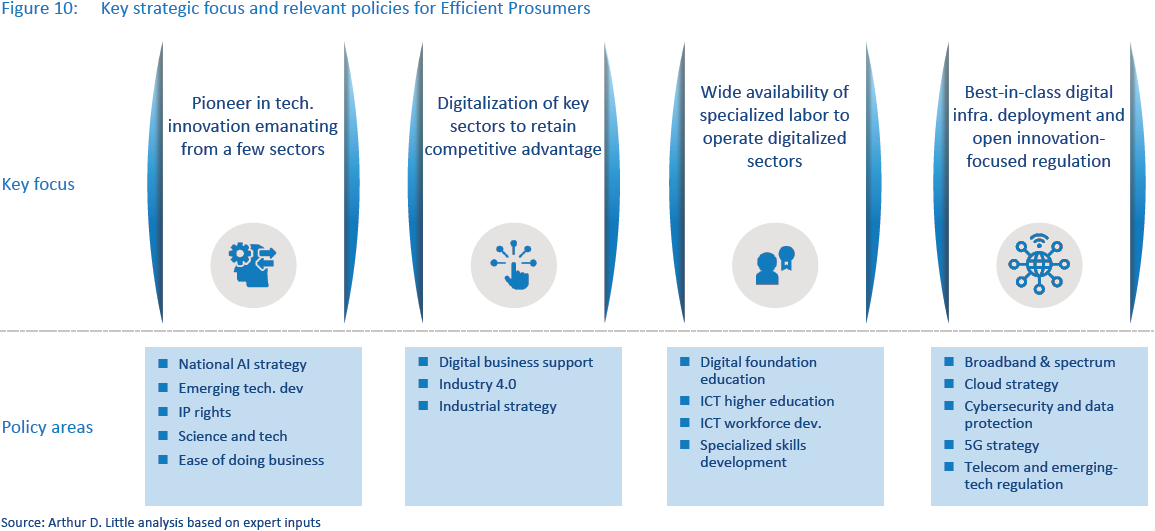

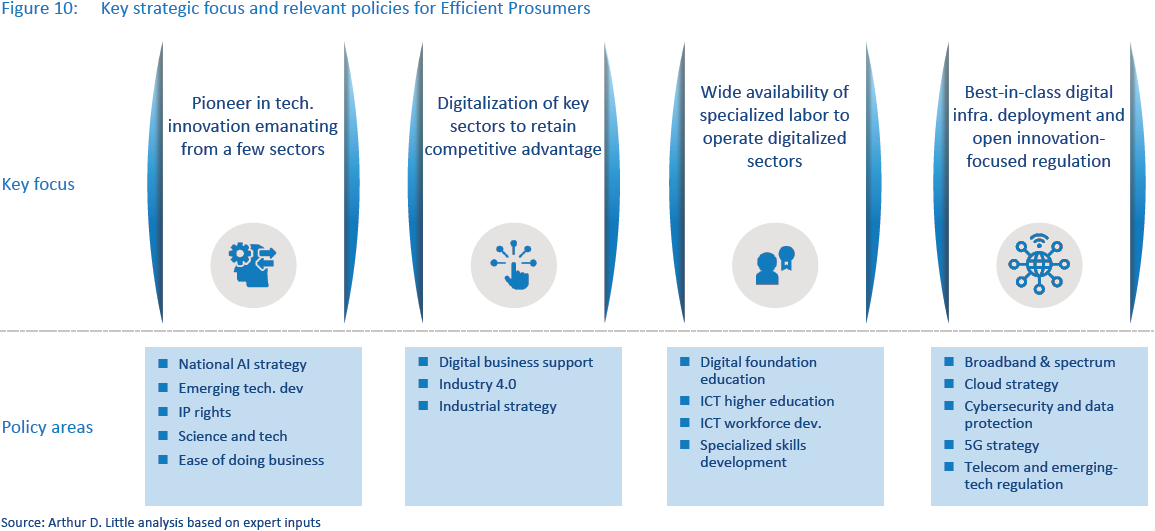

3.1.2 Efficient Prosumer

The overall strategy for an Efficient Prosumer is to drive technology innovation in a few dominant local industries to enhance economic competitiveness globally. Consequently, the key strategic objectives of an Efficient Prosumer are to:

- Become a pioneer in technology innovation emanating from selected dominant sectors.

- Digitalize key dominant sectors to retain competitive advantage.

- Ensure wide availability of specialized labor to operate digitalized sectors.

- Deploy best-in-class digital infrastructure and open innovation-focused regulation.

Each of these strategic objectives can be strengthened through efforts across various policy domains.

Pioneer in technology innovation emanating from selected dominant sectors

Efficient Prosumers aim to become pioneers in innovative technology development and commercialization, with specialization in a few sectors. For instance, Germany is characterized by innovating in well-established industries to keep its worldwide leadership position in sectors such as automotive, chemical, mechanical, electronic, materials, and, more recently, renewable energies. To achieve such a goal, Efficient Prosumers should have comprehensive AI and emerging technology development policies aimed at encouraging innovation and fostering business investments and technology commercialization in the dominant sectors.

In addition, governments should directly provide funding or mentoring, or set up specific hubs for companies focused on developing innovative solutions. Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy has over eight funding programs aimed at providing capital for pre-commercial research and development projects to help transform scientific findings into state-of-the-art technology that can then be sold in the market. Robust IP rights protection is also critical to promote private sector participation in R&D in the country. Furthermore, Efficient Prosumers may support the growth of digital businesses through the adoption of conducive EoDB policies – for example, streamlining the process of starting a business through the aid of digital platforms, reducing costs of licenses, and removing financial barriers such as minimum-capital requirements.

Digitalization of key sectors to retain competitive advantage

To maximize the benefits of innovation efforts, Efficient Prosumers seek to incorporate locally developed digital solutions into key sectors to increase productivity and retain competitive advantage. Specific sector policies serve this purpose; some examples include Industry 4.0, fintech and e-health strategies. Initiatives within these strategies should foster the demand for digital technologies across all business sizes; some options include the provision of financing incentives to those emerging technologies in industry, capability-building activities, infrastructure enhancement and spaces to trial new technology solutions. Germany’s Industry 4.0 strategy is a policy reform that aims to drive digital manufacturing forward by increasing digitization and the interconnection of products, value chains and business models. It also aims to support research, networking of industry partners and standardization of cyber-physical systems. Since many public, private and academic entities are engaged in the German industrial innovation landscape, the country established “Platform Industrie 4.0” to serve as a point of contact for policy makers and guide public efforts around the topic.

Wide availability of specialized labor to operate digitalized sectors

Driving digital transformation at an advanced level requires extensive availability of a specialized workforce that can operate effectively in the digitalized sectors. Policy makers need to consider reforms across the entire education system to guarantee that the country is building strong digital foundation skills in schools. This will help build both interest and capabilities for students to pursue careers in STEM tertiary education or follow advanced technical vocational paths. To increase the number of specialized professionals, countries should enhance the supply of local workers or attract skilled foreign workers. The former may be achieved through scholarships for STEM degrees, subsidized vocational education, and technical centers, while the latter may be attained by establishing incentives for foreigners. In Japan, a country facing workforce challenges from an increasingly aging population, the government has launched the “Highly Skilled Foreign Professional” working visa, which is designed to attract highly skilled professionals across 14 industry fields to work in Japan by giving them preferential visa processing and residency benefits.

Best-in-class digital infrastructure deployment and open innovation-focused regulation

Digital infrastructure plays a central role in enabling advanced sector digitalization. Efficient Prosumers should have stateof- the-art ICT infrastructure as a foundation to support development, commercialization and adoption of emerging technology solutions. As investment costs in passive infrastructure can be very high, governments may intervene through regulation and funding to encourage universal fiber deployment. 5G networks are also key to supporting emerging technologies, particularly to enable cyber-physical systems, which are expected to prevail in industries such as manufacturing, mining and logistics. In terms of storage and data processing, cloud adoption presents the biggest benefits, as it enables cost-savings and enhanced productivity through easier collaboration, and fosters innovation as new business models are enabled.

As in the case of Innovation Hubs, an adaptive regulatory regime is crucial to drive innovation of use cases in emerging technologies. In Germany, for instance, The Data Ethics Commission recommends adopting a risk-adapted regulatory approach to algorithmic systems, which are key in AI technology solutions. It states that the greater the potential for harm, the more stringent the requirements and the more far-reaching the intervention by means of regulatory instruments. In other words, it recommends that regulation adapts to the potential risk of the emerging technology.

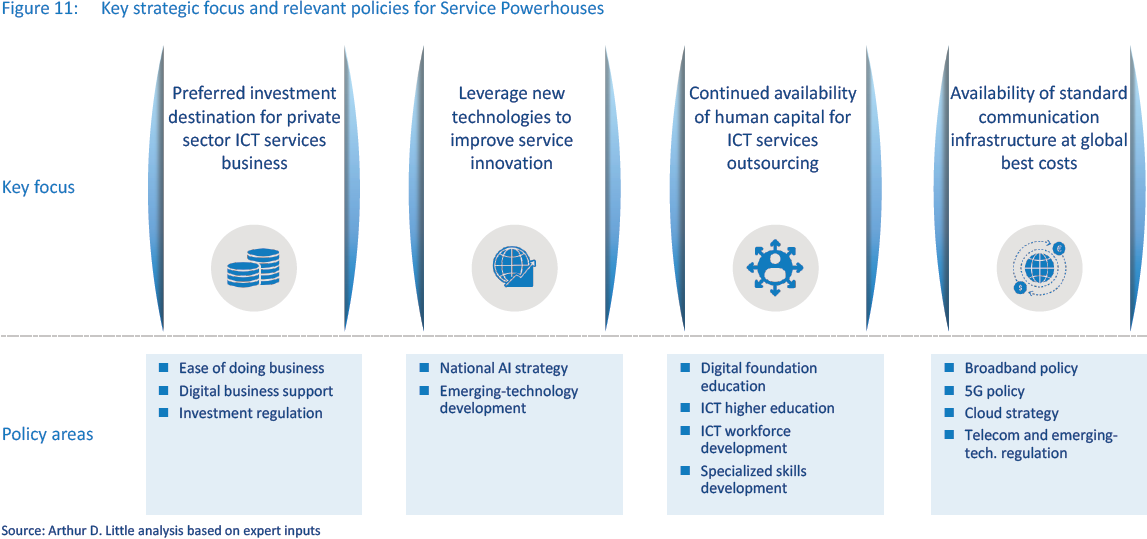

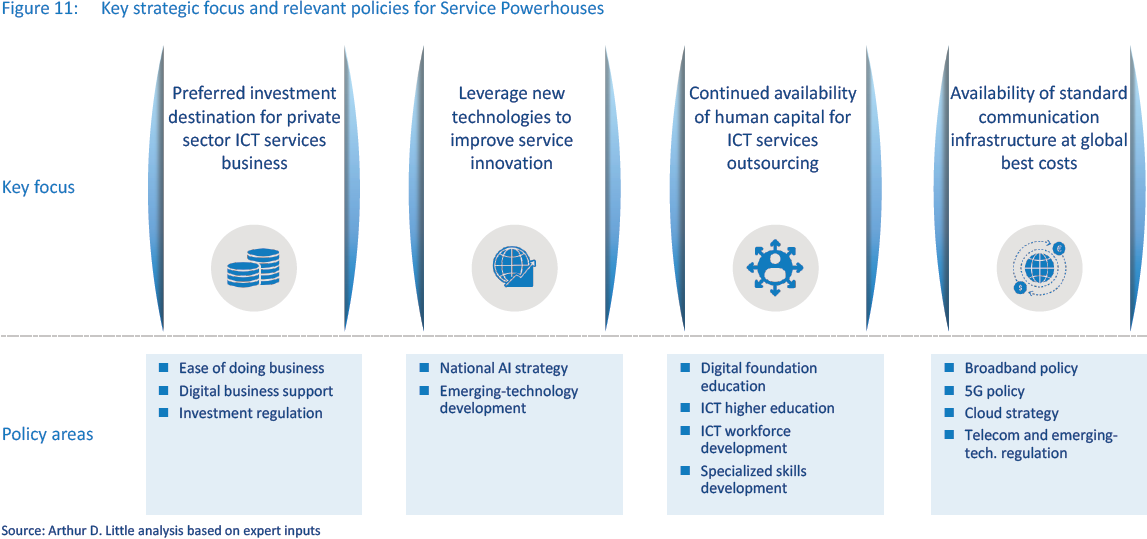

3.1.3 Service Powerhouse

The overall strategy of a Service Powerhouse is centered on improving investments and capabilities to drive ICT services business. Consequently, the key strategic objectives of a Service Powerhouse are to:

- Be a preferred investment destination for private sector ICT services business.

- Maintain availability of human capital for ICT services outsourcing.

- Leverage new technologies to improve service innovation.

- Maintain availability of standard communication infrastructure at global best costs.

Each of these strategic objectives can be strengthened through efforts across corresponding policy domains.

Preferred investment destination for private sector ICT services business

To increase private sector investment in ICT services from local businesses and multinational companies (MNCs), Service Powerhouses need robust EoDB policy reforms, investmentenabling regimes and digital business support policies. This may include attractive taxation policies for the services sector, easy access to capital and flexible labor market regulations, and funding support. Ireland, one of the largest ICT services exporters in the world, provides a flexible and pro-business environment, as well as a competitive corporate tax regime. These have encouraged most of the largest global technology companies to establish their European headquarters there.

Leverage new technologies to improve service innovation

Service Powerhouses need to leverage new technologies to improve service delivery capabilities and stay relevant and competitive in an increasingly digital world. Substantial investments in emerging technology and AI, specifically targeted at use cases for service innovation and emerging technology skill development, are critical for this archetype to sustain its positioning. AI policy typically aims at enhancing and empowering human capabilities to address the challenges of access, affordability, shortage and inconsistency of skilled expertise in Services Powerhouses.

Continued availability of human capital for ICT services outsourcing

To grow and sustain the ICT services industry, Service Powerhouses should ensure access to large pools of human capital well-versed in ICT skills. To achieve such a goal, they may use ICT higher education and ICT workforce development policy initiatives, such as expanding the availability of ICT degrees at affordable prices, reskilling their current workforces into ICT roles, providing ICT apprenticeships for recent graduates, or attracting foreign talent. To increase the number of tertiary graduates with ICT skills, Ireland introduced the “ICT Skills Conversion” program, which targets tertiary graduates who do not have existing backgrounds in ICT. They are invited to join a free, highly practical one- to two-year ICT course with national validity. Service Powerhouses may also drive upskilling by establishing partnerships with private sector technology providers to develop programs that support the growth of ICT skills in the population. In Brazil, the government has built a massive open online course platform with the aid of large technology firms and local academic institutions. It delivers over 53 free courses in basic ICT, programming, emerging technologies and games content development, among others. In just over a year, the platform has already seen more than 400,000 students enrolled and over 3,800 teachers delivering the courses.

Availability of standard communication infrastructure at global best costs

Enhancing communication infrastructure at global best costs is also a key strategic objective for Service Powerhouses. As such, infrastructure will support the unique needs of ICT services businesses. Policy makers should incentivize the private sector to increase its investment in broadband infrastructure by directly subsidizing it or providing tax breaks. Conducive reforms to telecom regulation may also encourage broadband deployments. Service Powerhouses should consider establishing market liberalization laws, promoting rights-of-way (RoWs), enforcing infrastructure sharing, and ensuring regular pricing monitoring. Growing the ICT services ecosystem requires that businesses place a lot of trust in security of data stocks and flows. Service Powerhouses should ensure robust cybersecurity regimes. Ireland established the National Cyber Security Centre and developed a comprehensive set of measures around protecting key critical national infrastructure and the security of Government systems and data. These measures also embrace a broader set of issues around skills, enterprise development and cybersecurity research.

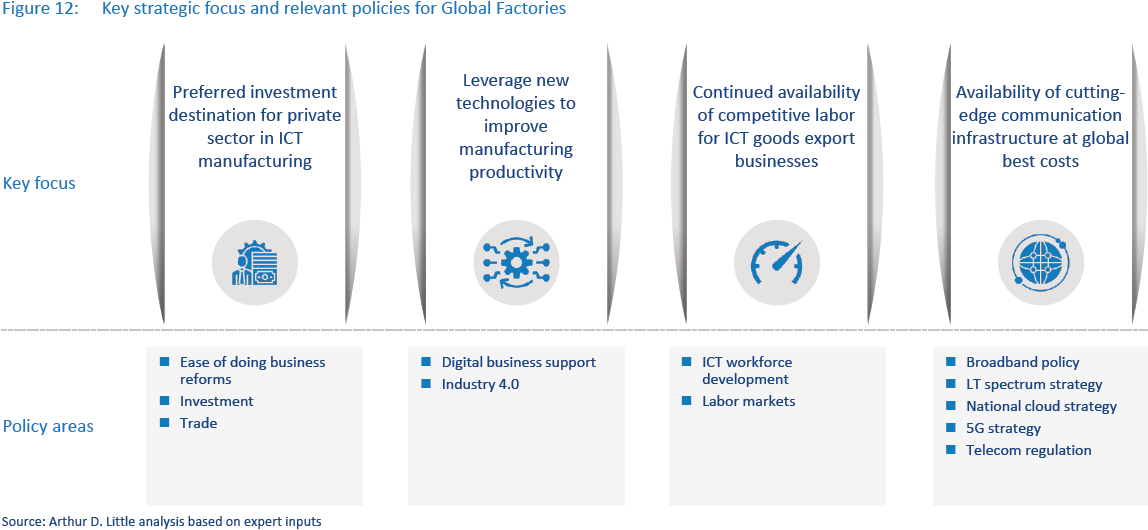

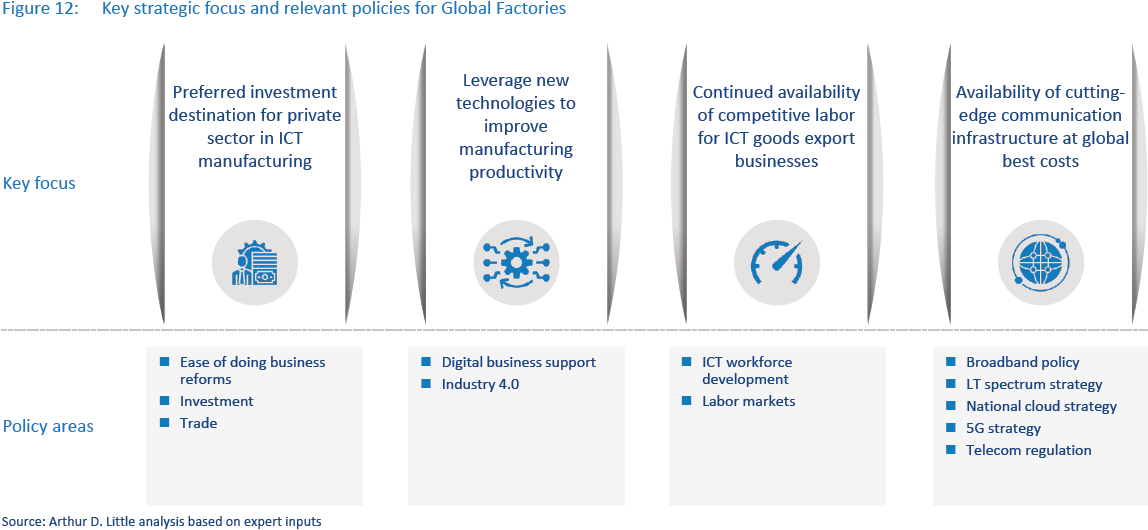

3.1.4 Global Factory

The overall strategy of a Global Factory is to remain a competitive location for ICT goods manufacturing. Consequently, the key strategic objectives of a Global Factory are to:

- Be a preferred investment destination for private sector ICT manufacturing.

- Maintain availability of competitive labor for ICT goods export businesses.

- Leverage new technologies to improve manufacturing productivity.

- Maintain availability of standard communication infrastructure at global best costs.

Each of these strategic objectives can be strengthened through efforts across various policy domains.

Preferred location for the private sector for ICT manufacturing

Global Factories need to attract private sector investments in ICT manufacturing through EoDB initiatives such as enabling the processes necessary to set up manufacturing facilities and providing world-class supply-chain infrastructure, access to capital, and fiscal incentives to export such products. Thailand moved up six places to 21st out of 190 countries in the World Bank’s 2020 EoDB rankings by streamlining the approval process for doing business, adopting digital systems for government services, and improving rules and regulations to catch up with changes in business. Pro-investment and trade agreements are extremely critical for Global Factories. Furthermore, to ensure that small and medium enterprises (SMEs) also take part in the growth of the ICT manufacturing sector, governments may introduce support in the form of technical and financial assistance for promising SMEs. In Thailand, where SMEs are the backbone of the economy, the Ministry of Industry issued a $950 million fund for 2020, which can be accessed by SMEs in various sectors, including ICT.

Leverage new technologies to improve manufacturing productivity

Another strategic objective of Global Factories is to leverage new technologies to improve manufacturing productivity to remain globally competitive. To achieve this, countries may develop Industry 4.0 strategies with specific objectives, policy roadmaps, governance models and sufficient budget. A strong Industry 4.0 strategy is composed of initiatives to grow the supply of technology solutions and increase the demand and adoption. Since Global Factories are not necessarily producers of emerging technology solutions, they may need to attract foreign firms to locate offices in their countries or offer attractive importtax regimes to encourage the flow of industrial technology solutions into their markets. To encourage adoption, policy makers may set the example by procuring emerging technology solutions for some of their industrial projects in the utilities or transportation space. They may also provide digital business support to enhance digitalization. Malaysia has introduced a national “Industry 4.0” policy framework aiming to implement standards for systems interoperability for smart manufacturing. Similarly, Thailand established its “Thailand 4.0” strategy, targeting 10 industries in the hope of their serving as new and more sustainable growth engines. However, neither strategy has seen much advancement in terms of implementation yet.

Continued availability of competitive labor for ICT goodsexport businesses

Global factories should also target continued availability of competitive labor to meet the evolving business needs of ICT goods businesses. Particularly, they must ensure that labor is able to adapt to the introduction of new technologies into ICT manufacturing operations. The current workforce will need to be proficient at using cutting-edge facilities for tooling, production process design, testing and calibration. To facilitate a steady flow of cost-competitive labor, governments may advance vocational training programs, introduce Industry 4.0 capability centers to upskill their current workforces, or provide tax incentives for private companies to drive training efforts. In Mexico, the government has set up 98 centers for industrial innovation across the country to promote training in Industry 4.0 technology use cases. In Thailand, the government provides up to 200 percent corporate tax breaks for companies investing in upskilling employees in digital skills.

Availability of cutting-edge communication infrastructure at global best costs

The entire ecosystem will require cutting-edge communication infrastructure; hence, Global Factories should develop long-term digital infrastructure strategies that can support their target to become advanced manufacturing hubs. 5G connectivity will be a key digital enabler for this archetype, as it will permit the adoption of several emerging technology solutions in industrial sites through deployment of campus networks. Consequently, fiber deployments will be crucial to support 5G rollouts and for improved connectivity. Ensuring healthy competition among telecommunications infrastructure and services providers can be key to enhancing the speed at which broadband policy targets are achieved, as well as ensuring affordable connectivity prices for all. The Malaysian Communications and Media Commission introduced the Mandatory Standard on Access Pricing (MSAP).

The MSAP regulates prices and terms for alternative internet service providers (ISPs) to access the incumbent’s wholesale broadband capacity. This allows alternative ISPs to offer lowerpriced and higher-quality services to their subscribers.

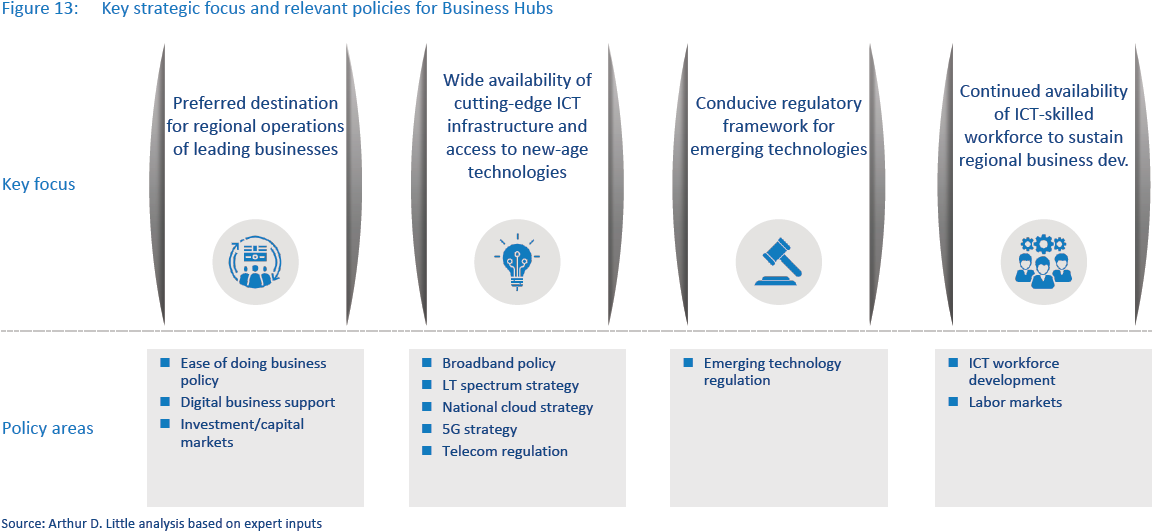

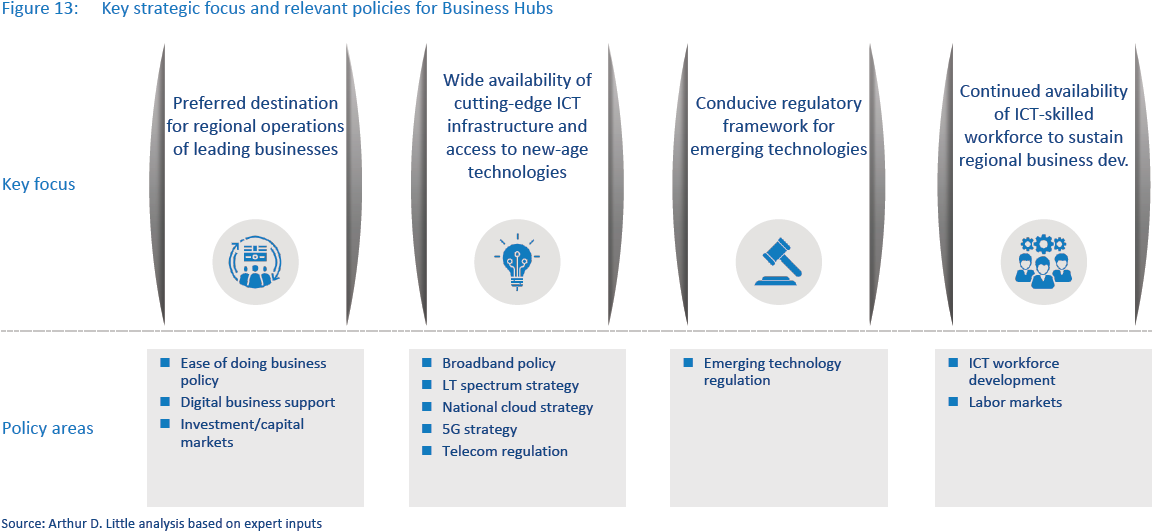

3.1.5 Business Hub

The overall strategy of a Business Hub is to become the most lucrative regional trading destination, encouraging firms across the world to set up their key offices there. Consequently, the key strategic objectives of a Business Hub are to:

- Be a preferred destination for regional operations of leading businesses.

- Maintain availability of an ICT-skilled workforce to sustain regional business development.

- Provide a conducive regulatory framework for emerging technologies.

- Maintain wide availability of cutting-edge ICT infrastructure and access to new-age technologies.

Each of these strategic objectives can be strengthened through efforts across various policy domains.

Preferred destination for regional operations of leading businesses

Attracting foreign companies to set up their HQs and operational offices requires a conducive business environment. EoDB policy options to stimulate private sector relocation to Business Hubs include enhancing ease to access other markets, streamlining importing and exporting activities, providing financial incentives to set up companies, and ensuring easy access to talent. In the UAE, government policies have been focused on streamlining registration and approval processes, especially in commercial areas such as Dubai and Abu Dhabi. For instance, the local government launched the Bashr platform, an integrated e-service which enables investors to establish their businesses in the UAE within 15 minutes through a unified online platform.

Wide availability of cutting-edge ICT infrastructure and access to new-age technologies