DOWNLOAD

DATE

Contact

New growth outside the core business is at the top of the CEO agenda for many companies in mature sectors. Large food and beverage companies are in a race to increase the “rate of change,” deploying a variety of strategies to stay flexible, broaden their product portfolio, and keep their brands relevant. Traditional innovation methods of investing in internal R&D or rolling up start-ups are not rapidly creating and developing new step-out business quickly enough. Considering new innovation models that take innovation outside day-to-day ecosystems can help companies that are unsatisfied with current breakthrough innovation performances.

Large food and beverage companies were once able to lead broad segments of the market to their most profitable brands and products. Not anymore. With power shifting to smaller, more demanding groups of consumers, the on-demand spirit of other industries is catching up to the powerhouses of this industry.

Leaders have been feeling the pain – an estimated $4.5 billion in revenues has been ceded to small companies, and more than 15 CEOs of US packaged-food companies have left their jobs since 2016. In the search for growth, the multiple for deals valued at more than $1 billion jumped from 13 to 20 times EBITDA from 2016 to 2017. There’s also been a bandwagon of big food companies setting up incubators and accelerators to better leverage the capabilities of start-ups; for the most part, however, results have been drops in the ocean compared to core business.

Big brands desperately need more effective innovation strategies to help them stay ahead of shifting demands and, ultimately, increase shareholder value. This is clear whether it is driven by the need for growth, better sustainability and ethics; the impact of commodity cost increases; changing consumer preferences; channel disruption; digitalization; or health and wellbeing.

CEO challenge: Untangling space and time

To some degree, what food and beverage companies are seeing is just one example of a megatrend affecting all consumer businesses. There have been significant changes in two basic dimensions. First, there is an unparalleled requirement to consider potential extensions to the scope of the business (“space”); and second, there has been huge acceleration in the required pace of the business (“time”).

Consumer mindsets are in what can appear to be a continuous sea change, primarily driven by the millennial generation. The modern consumer places increasingly high value on the authenticity of a company’s long-term purpose, while simultaneously demanding responsiveness and adaptability to change. Essentially, consumers are looking to companies, their brands, and their products as extensions of themselves. Standard products must be, or represent more than, the sum of their parts.

This shift has led to the emergence of a new ecosystem in which previously unheard-of parties are jointly experimenting and collaborating to innovate and match customer and consumer appetites and imaginations – these include not just companies, but also customers, communities and crowds.

Time is also accelerating more quickly than many thought possible only a decade ago. Technology, globalization, social norms, and economics are all underlying factors contributing to a trend of “everything faster” – in both the context of our personal lives and business. The implications for business are higher expectations for more rapid decisions, faster and continuous innovation, faster time to market, and shorter ownership and alternatives to ownership.

Campbell’s Soup is one high-profile example of a food and beverage company that has struggled to keep pace with the rate of change. While making a series of costly acquisitions to move into areas such as fresh food and snacks, it failed to meet forecasts for successive quarters in 2018, and the CEO, Denise Morrison, stepped down.

New, step-out businesses falling short

For companies in established, mature businesses with lowsingle-digit growth prospects, or in which technological disruption is threatening to erode or even destroy the current business, this challenge of expanding space and tightening time is critical to keep up with the market, and even exist.

Acquisition is clearly one route to consider, but as illustrated by Campbell’s, it can be extremely expensive and risky. Innovation is another route to growth, but creating new businesses requires “breakthroughs” and is unlikely to be delivered by core R&D.

Consequently, companies have created stand-alone, semiindependent breakthrough innovation teams and are using vehicles such as start-up incubators, accelerators and corporateventuring schemes. Coca-Cola, Danone, 3G Capital, and most recently, Tyson Foods – with its significant equity stake in plantbased protein company Beyond Meat – all offer examples of these approaches in practice.

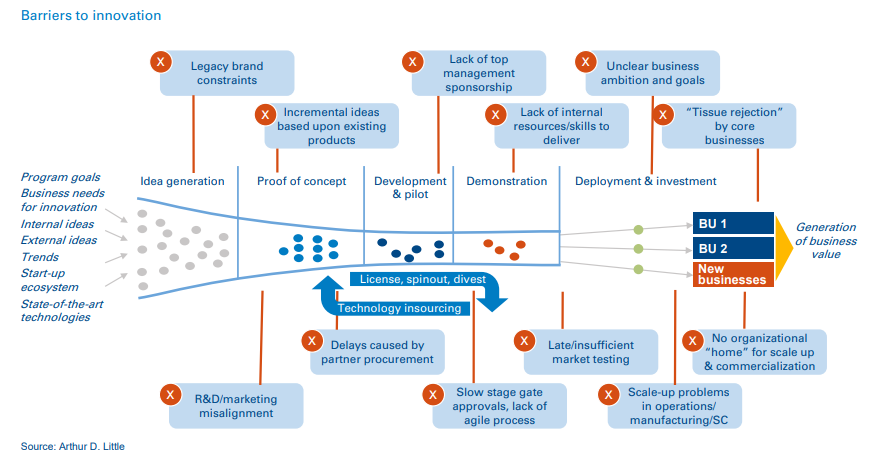

Despite some successes, these initiatives are trending in the wrong directions, falling short of their expectations for creating significant new business growth. For example, in a recent Arthur D. Little (ADL) breakthrough innovation survey, more than 85 percent of companies were unsatisfied with their breakthrough innovation performances. There are several reasons for this:

- Failure to go beyond the prototyping stage: Many innovative prototypes falter when more thorough market/ consumer testing is conducted, or when the practicalities of large-scale material sourcing and manufacturing are properly assessed

- Internal rejection of radical new products: Many large companies have built-in “antibodies” that hinder or reject radical new innovations, especially if they are seen as threats to the current business.

- Brand and receptivity constraints: In most B2C and some B2B businesses, brand is king. Sometimes great new innovations are killed prematurely because they don’t easily fit with the existing portfolio of brands, or because they can’t find “homes” within the current business unit structure.

- Lack of resources and capabilities: Often there is not enough resource availability to pursue non-core innovation, or the company lacks the right in-house capabilities to support growing a new, non-core business.

- Scale-up risks: In many companies, concepts and prototypes can stay on hold for years, either without being properly commercialized or finally being killed off. This is often due to the level of investment required for scale-up and the perceived high residual risks, combined with reluctance to give up on pet projects.

In other words, lack of success can often be attributed to not only one, but multiple, roadblocks across the innovation cycle – from robust concept development, to appropriate design of consumer and market tests, to scale-up and commercialization with senior management support.

Breaking through with a new innovation model

The Breakthrough Incubator (BI) model is a new approach to help overcome innovation roadblocks. In the BI model, the end-to-end innovation process is externalized and conducted by a lead delivery partner managing a network of other players, from ideation through to launch and commercialization. This includes strategic, commercial and operational planning, as well as technical development.

The BI model can provide new business creation at a fraction of the cost of a large-scale acquisition, and is substantially faster and cheaper than internal development. And, while the BI model mitigates risk, primarily by keeping the project external and brand anonymous until it is largely proven in prototype and full scale, companies may instinctively feel that externalizing a complete, end-to-end innovation program is too risky.

To mitigate potential risks, it is important for companies to implement five key success factors when applying the BI model:

- Top management commitment: Because an end-to-end innovation program cuts across many different functions and potential vested interests, top management needs to be an active sponsor to ensure lack of interference during development and smooth transitioning back into the company.

- Ensure clear scope and governance: Agree on the scope, ambition, tasks, deliverables and milestones very clearly, and with sufficient detail, at the outset. Split execution into discrete phases with separate budgets. Establish a joint steering committee with senior executives from both the company and the BI partner.

- Use an agile approach: As much as possible, use an agile approach in the development phase, with early prototyping, rapid quantitative and qualitative testing in the marketplace, and seamless integration across strategic, technical, commercial and operational functions.

- Maintain arm’s-length independence during development: To ensure freedom from overall corporate interference and maintain confidentiality, keep contact only with the nominated guidance team during development.

- Provide a comprehensive transitioning process: Ensure that the transition back into the company includes structured interactions with all key internal stakeholders involved, and fully captures the insight and lessons learned.

BI in action: Overcoming innovation hurdles in food and beverage

A leading food and beverage company set out to target new segments of the consumer population by developing innovative products tailored to consumers’ specific needs. It wanted the initiative to be consumer-needs led, scientifically and quantitatively driven, and independent of its existing portfolio of businesses and brands. While the initiative was aimed at developing and launching new products and platforms, it was also focused on learning and bringing the organization up to speed on the targeted segments, as they were deemed important future growth drivers.

With the help of ADL, the company created an “incubator” outside of its own organization with the charter to ideate, create, develop, test, and launch new products that fulfilled the strategic objectives. As the project orchestrator, ADL created and implemented an agile approach using an ecosystem of collaborators that met the needs of every step of the project. ADL also coordinated with the client team regularly to ensure input and buy-in to critical decisions and milestones. While only a fraction of the concepts developed as parts of this project ended up being launched, an important benefit to the client was the creation of a portfolio of concepts/products and future brands that could be introduced to the market as parts of subsequent launches. The insight and learnings about the segment’s emotional and functional needs would also form the basis for development of strategic platforms, around which the client would transform the business to focus on key growth segments of the future.

Innovating to bend space and time

Large food and beverage companies have traditionally had a fairly simple approach to innovation, based around conducting consumer research via existing brands/products, generating ideas that were often incremental due to the type of consumer research conducted, formulating a few recipes, and testing prototypes with consumers.

This approach may have generated positive results when large food and beverage companies dominated the market, but these organizations now need to become more strategic in their innovation approaches if they want to avoid further decline, or even destruction. They need to have clear direction in terms of how to grow beyond stagnant or declining core businesses, making the most of the levers available to them – this includes not only internal R&D and acquisition, but also the huge potential of the external innovation ecosystem.

Forward-thinking leaders should consider models that help them bend space and time. By taking innovation outside their day-today ecosystems, they can overcome the “tyranny of the brand” and deliver real, step-out innovation-based growth in a controlled and systematic way.