DOWNLOAD

DATE

Contact

Integrated telcos undergoing separation/asset reconfiguration must carefully balance several factors, not least of which is regulation. The regulatory benefits from asset reconfiguration strongly depend on: (1) the type of separation model being adopted, (2) strategic resolutions spelled out in the master service agreement (MSA) between separated entities, and (3) local regulations. Consequently, there must be a careful assessment at all decision-making levels to “ace” the regulatory exam.

The telecom industry is experiencing a period of profound revolution resulting from digital transformation and changes in connectivity consumption, leading to massive investment in next-generation networks, such as fiber to the home (FTTH). This change suggests that asset reconfiguration and separation of InfraCos (typically consisting of the infrastructure layer [NetCos or FiberCos]) and ComCos (typically including the active and commercial layer) could unlock substantial value for operators.

A recent Arthur D. Little (ADL) Viewpoint, “Navigating Fixed Asset Reconfiguration in Telcos,” identified the following drivers of asset reconfiguration/separation:

-

An increasing interest by new long-term investors (infrastructure funds, pension funds, and utilities) in infrastructure assets in the telco value chain (driven by high valuations)

-

Downward pressure on CAPEX-to-sales ratios for integrated telcos, creating tension between infrastructure CAPEX cycles (5G and FTTP deployment) and ComCo investments, and stimulating the need for new funding structures

-

Fundamentally different business models (i.e., investment horizon, internal rate of return [IRR], CAPEX cycles, risk profile) of InfraCos versus ComCos, leading to internal tensions and misalignment

-

Increased pressure from competitors seeking attractive anchor tenancy deals to fuel their growth

However, these dynamics and the related benefits of such initiatives can be impacted by the regulatory regime applied to the specific operator and the possible deregulation outcomes as well. This Viewpoint offers a hands-on perspective on the main levers for consideration when assessing the potential regulation impact of a telecom reconfiguration.

Regulatory relief arising from reconfigurations is strongly dependent on the separation model adopted (i.e., structural versus legal or functional separations), as regulators are keen to ensure effective competition and nondiscrimination. Generally speaking, operators can split their infrastructure and retail service in several ways, ranging from purely functional separations (e.g., Open Eir’s establishment within Ireland’s Eir) to the creation of legally distinct entities under joint control (as happened with British Telecom [BT]) to structural separations (e.g., Italy’s recent NetCo/FiberCop), where the two entities are controlled by different shareholders.

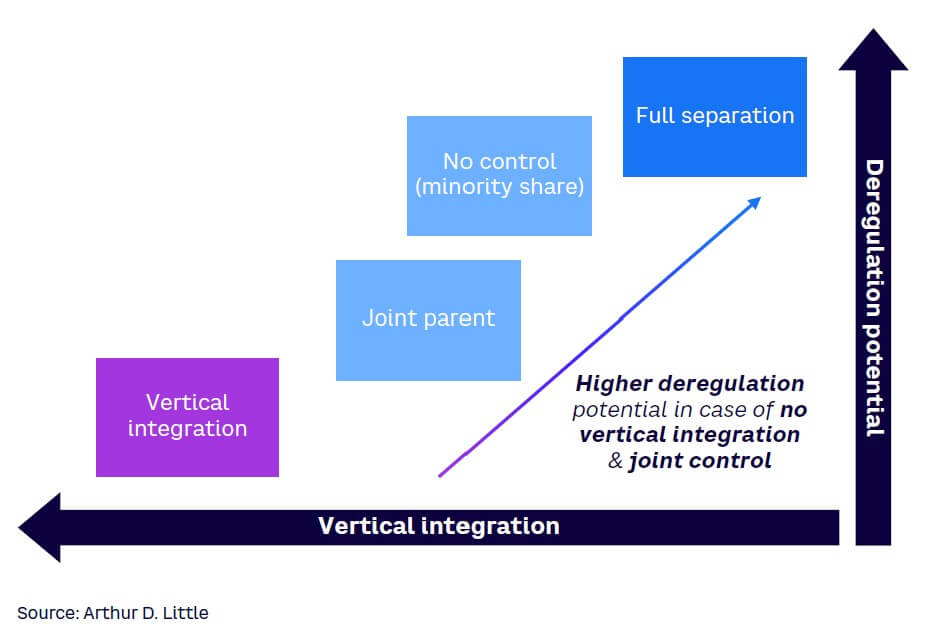

However, as regulators aim to avoid discrimination and the potential for downstream damage from reduced competition, the occurrence of deregulation depends mainly on the expected competitive condition of the market (i.e., the presence of significant market power [SMP]) and how the interrelationships between the two entities are managed (see Figure 1). In particular, regulators are concerned with:

-

Any vertical integration still in place after the reconfiguration process

-

The parent relationship that will or might exist between the two entities

-

The degree of operational and strategic independence for the InfraCo/ComCo

At the same time, previous telco separations show that, when effective independence is guaranteed, deregulation can be expected for the ComCo as far as retail prices are concerned, while the InfraCo regulation will be driven by the level of infrastructure competition in specific areas (subnational level) and any wholesale-only regulations (e.g., Article 80 of the European Electronic Communications Code [EECC]).

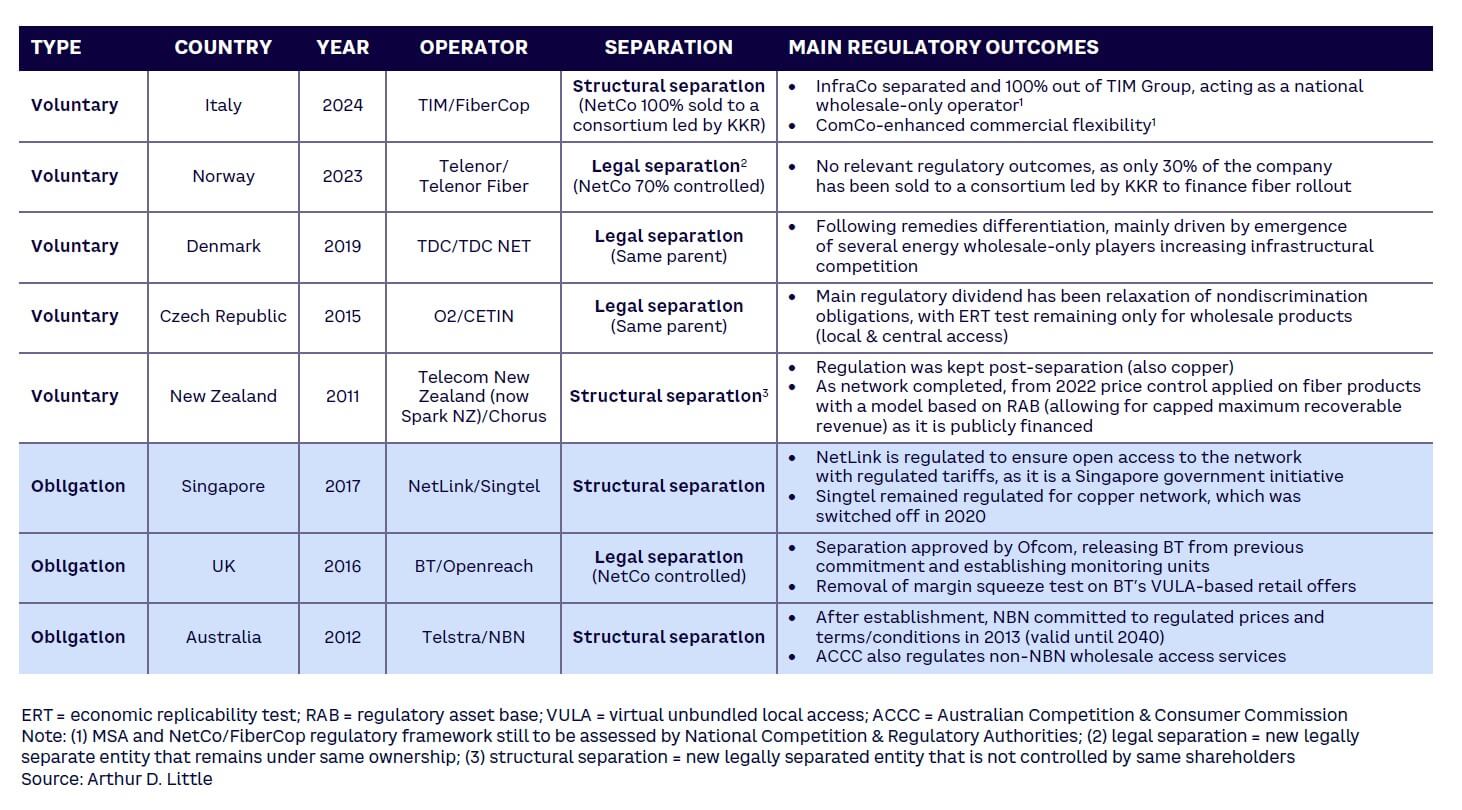

To date, only a few reconfiguration/separation initiatives have been carried out as a direct consequence of regulatory obligations. Although several large telecom operator reconfiguration initiatives took place in the last decade, few stemmed from regulations being imposed on the incumbent. Rather, reconfigurations such as Openreach/BT, the Australian National Broadband Network (NBN), and Singapore’s NetLink were implemented as a result of government plans for infrastructure deployment.

NBN was created to deploy the public-funded next-generation access network, with the incumbent Telstra pushing to confer its infrastructural assets. NetLink was established as the national fiber InfraCo in compliance with the government’s 2005 broadband strategy and in 2017 requested to be separated from Singtel to guarantee independence and interrupt vertical integration. The UK decision did come from regulatory authority Ofcom (Office of Communications) to limit identified anti-competitive practices by BT in influencing the previously functionally separated Openreach’s network investments, but it was closely linked with expanding fiber (which in 2016 covered less than 5% of UK households).

In many cases, separation was accompanied by a cash infusion from private investors to ensure the country would have sufficient capacity to deploy the new networks. For example, in the Czech Republic, PFF acquired O2 and performed the split to create wholesale-only CETIN. In Denmark, the separation occurred following the incumbent’s acquisition by a consortium of local and international funds. A similar case exists in Norway, where an investment fund consortium owns around 30% of the newly established Telenor Fiber. The recent TIM NetCo separation and 100% acquisition by a consortium led by KKR in Italy follows this pattern. Outside Europe, the New Zealand case of Telecom New Zealand (now Spark NZ) and Chorus, the only voluntary structural separation thus far, was performed mainly to participate in the publically funded FTTH investment.

Other key levers for separation include providing new entities with enough flexibility to compete in the changed competitive environment and/or to preempt expected regulatory pressure. For example, O2 CETIN has experienced considerably more freedom to pursue new lines of business, and Telecom New Zealand freed itself from excessive organizational complexity.

The regulatory consequences of a separation vary for the InfraCo and ComCo. For InfraCos, impacts on regulatory frameworks strictly connected to restructuring have been limited so far. This may be attributable to the fact that, in a few cases, the separations were “structural” (see Table 1) and presented a full change of control of the separated entity, or the InfraCo was a public initiative (i.e., Chorus in New Zealand or Singtel in Singapore). The game changer in those cases was the changed infrastructural competitive environment. In Denmark, the latest market analysis resulted in strong geographic differentiation, and the SMP designation was given to several utility operators developing fiber in their core areas. In the UK, the relaxation of fiber price control in competitive areas was linked to the presence of several small local infrastructure operators.

The direct benefit of a separation stems from the relaxation of ComCo obligations. The removal of vertical integration dismisses the prerequisite for the imposition of ex ante margin squeeze tests, resulting in more commercial freedom.

This happened in both the Czech Republic, where increased retail flexibility was among the pillars of the unbundling strategy of the PFF fund, and in the UK, where the imposition of the margin squeeze test on virtual unbundled local access (VULA)–based retail offers was removed from BT in 2018.

REGULATORY IMPACTS HIGHLY INFLUENCED BY STRATEGIC DECISIONS

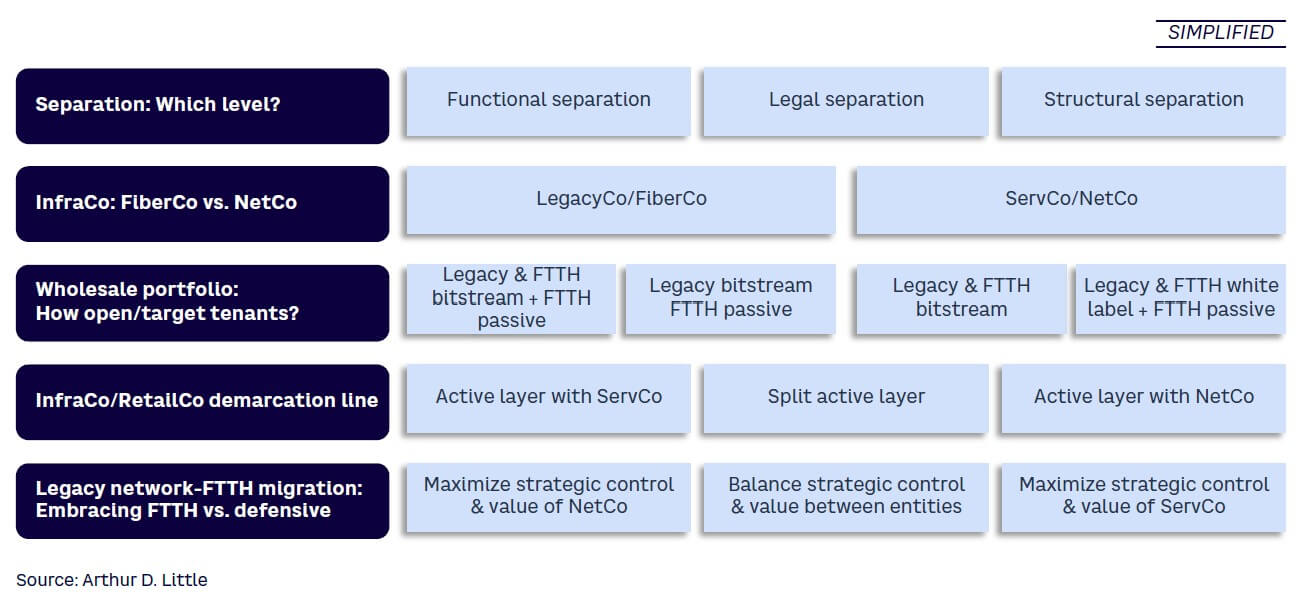

Some key strategic decisions, including asset demarcation and MSA dynamics, play a role in determining deregulation potential. It’s important to remember that value creation is highly dependent on local market structure because major trade-offs must be optimized for fixed infrastructure assets. Several dimensions impact possible regulations, in light of a new or revised framework:

-

Level of separation. How close will the entities remain? Separations range from purely functional to the establishment of a separate entity in which shareholder contributions are likely to drive major differences in the imposed regulations.

-

FiberCo versus NetCo. Will the InfraCo be a purely fiber company or a more comprehensive entity that includes the legacy network (copper or coax)? Here, value creation is highly dependent on the residual value placed on the legacy network, the related decommissioning plan, and regulatory relief based on the remaining vertical integration with the legacy network in cases where just a FiberCo is established.

-

Wholesale portfolio. Target commercial positioning can range from all-access network services (aimed at attracting the largest volume of other authorized operators [OAOs]) to more contained solutions such as passive-only or no passive service provision, aimed at maximizing InfraCo strategic control. However, the InfraCo’s product portfolio may be restricted by regulations that can require the operator to provide certain active/passive services.

-

InfraCo/ComCo demarcation. The demarcation line determines the value allocation between the two separated entities: in particular, the active layer allocation determines the differentiation potential of the companies. This strategic choice should consider the access services mainly adopted by OAOs as well as the access regulation in place (i.e., in cases where the VULA provision is regulated, parts of the active-related equipment are typically allocated in the InfraCo), along with the ambition to fully separate the retail versus the wholesale business to avoid overlap between the two separated entities.

-

Legacy network versus FTTH migration. There’s a strong interdependence between the ComCo’s commercial strategy and the wholesale agreement with the InfraCo. Key decisions include pricing schemes, purchase obligations, technology neutrality versus FTTH stimulus, and InfraCo deployment priorities. A careful balance should be struck to ensure both entities achieve their porfitability and ROI objectives and ensure no discrimination toward all OAOs (see Figure 2).

REGULATION REMAINS A LOCAL GAME

Major regional regulatory differences remain, even across European countries, both in terms of obligations and the way authorities approach current regulations. Country-specific characteristics in the telecom sector increase complexity and play a key role in shaping asset reconfigurations and perimeter definitions of InfraCos and ComCos. Highly competitive conditions in some countries (e.g., number/type of operators, presence of alternative infrastructures, ultra-broadband take-up) lead to major differences in the remedies imposed on national incumbents; the recent trend of adopting geographic differentiation has increased this complexity. Indeed, the proliferation of alternative operators focused on deploying new fiber networks has elevated infrastructure competition in several regions, leading to a gradual differentiation of regulatory obligations on new networks and, in some cases, the removal of price controls.

In particular, there are significant differences in the regulation of access technologies (copper and fiber) and network-access options for OAOs through passive services (physical unbundling) or active solutions. For copper, regulators historically compelled the incumbent operator to grant unbundled access to the copper network, either at the local exchange level through a local loop unbundling or at street cabinets through a sub-loop unbundling. Even in places where this approach was adopted for fiber, the introduction of VULA changed the regulatory paradigm for many; in most countries, VULA has replaced physical access to fiber.

Various regulatory regimes apply to VULA service (where regulated):

-

Pricing. This was based on cost orientation in a few cases (i.e., copper services), generally adopted through the application of long-run incremental cost models, including a risk premium on FTTH. However, for fiber and in more competitive contexts, less restrictive modalities have been adopted, including price cap, an economic replicability test, fair and reasonable prices (especially for VULA, or no price regulation beyond nondiscrimination (i.e., wholesale-only players).

-

Remedies differentiated by geography. This trend is increasing in Europe as alternative infrastructures are being built. It’s expected to grow as FTTH coverage increases and regional disparities remain in the cost per home passed.

Recent regulatory changes in Europe incent reconfiguration approaches to foster the development of very high-capacity networks (VHCNs) and preserve competition. At the end of 2018, the EU consolidated and reformed the sector’s regulatory frameworks within the EECC. The new framework places significant emphasis on promoting initiatives to support the development of VHCNs and related investments. In particular, it uses two instruments to define regulatory relief and incentives: wholesale-only operators (Article 80) and regulated co-investment (Article 76):

-

Wholesale-only operators. The policy aims to reduce the regulatory burden and impose fair and reasonable price obligations (versus cost orientation) and only if justified[1] to wholesale-only operators that comply with the following:

-

The commercial divisions and fully and partially controlled companies do not operate in the retail market.

-

The company is not bound to deal with a single, separate operator in the retail market.

-

In the case of a voluntary separation of a vertically integrated operator, the “wholesale-only” condition must be assessed by the national regulatory authority alongside a specific SMP assessment.

-

Regulated co-investment. The policy foresees the possibility of SMP operators opening up deployment of a new VHCN co-investment (e.g., by offering co-ownership or long-term risk sharing through cofinancing or purchasing agreements). If the offer is deemed to be compliant with the policy, the co-investment offer conditions replace the regulation with regard to the new network geographical scope.

Regulatory frameworks are significantly evolving to support fiber network rollouts:

-

Deregulation for (VHCNs). An important guideline on the expected forward-looking regulatory framework for access to VHCNs in Europe was included in the recent (2024) EU Gigabit Recommendation. The recommendation aims to ensure proper remuneration of fiber investments through the promotion of a market-based approach, reflecting the various competitive conditions in the EU. This would broaden the scope of price flexibility to be granted for fiber products and provide guidelines for migration from copper to fiber.

-

Reduction of ex ante regulation for wholesale access. A significant change in the reduction of ex ante regulation in a full fiber environment was proposed in a February 2024 European Commission white paper titled “How to Master Europe’s Digital Infrastructure Needs?”

CAREFUL REGULATORY ASSESSMENT & STRATEGY REQUIRED

The impact of regulations on reconfiguration scenarios can vary widely, so a careful assessment and a strategic positioning exercise should be conducted at all organizational and decision-making levels to “ace” the regulatory exam.

Shareholder/investor perspective

-

A full understanding of regulatory issues enables operators to anticipate framework developments, raising the level of certainty around business-case scenarios and future planning.

-

Regulation and deregulation dynamics between the InfraCo/ComCo allow for better capital allocation and value transfer, helping maximize value creation.

-

Regulatory positioning supports advocacy and industry cooperation, allowing for an active role in shaping regulation, contributing to the country’s digitization efforts and increasing the likelihood of ROI for investors.

Strategic planning perspective

-

Incorporating regulations into corporate strategy helps business leaders accurately identify risks and opportunities arising from changing market dynamics and new growth levers arising from regulatory developments (i.e., co-investment, price flexibility, services portfolio).

-

Accurate regulatory analyses provide more transparency when it comes to pricing dynamics, allowing leaders to better predict market potential for the InfraCo and giving them better insight into make-or-buy strategies for the ComCo.

Regulatory affairs perspective

-

Early identification of relevant issues helps leaders solve potential reconfiguration roadblocks faster and maximizes the chance of regulatory framework adoption by identifying key requirements.

-

Assessment of international best practices helps in supporting corporate positioning and expected post reconfiguration regulatory framework

Conclusion

MAXIMIZING RECONFIGURATION VALUE

Regulation must be carefully addressed at the early stages of any reconfiguration analysis to ensure maximum value:

-

Among asset-reconfiguration trade-offs, regulation or deregulation has the most potential to shape market dynamics and influence the new entity’s business case(s).

-

Regulatory frameworks are complex and highly dependent on country-specific factors, such as infrastructure development, effective competition, and national regulatory authorities’ assessment of the local markets.

-

Regulatory outcomes for reconfiguration are influenced by:

-

Key strategic decisions, including the type of separation, the asset perimeter, the demarcation line between InfraCo and ComCo, the target technology, and the tenets of the MSA

-

Evolution of the regulatory framework, which may include new provisions to incent reconfiguration types or regulation changes due to new regulator’s priorities

Note

[1] “… on the basis of a market analysis, including a prospective assessment of the likely behavior of the undertaking designated as having significant market power” (e.g., Article 80 of the EECC)