Maritime trade is essential for a smoothly functioning global economy. However, during the past five years, trade flows have been substantially disrupted by a range of factors, including the COVID-19 pandemic, geopolitical tension and conflict, and climate change, demonstrating vulnerabilities within the system. Many of these factors still impact maritime trade and will continue to do so. In this Viewpoint, we examine how countries can better manage risk factors and ensure supply chain resilience.

UNDERSTANDING THE CHALLENGES TO MARITIME TRADE

In a globalized economy, maritime trade is a critical part of a functioning supply chain, delivering necessary goods to businesses and citizens while ensuring food and energy security for countries around the world. According to the United Nations (UN), over 80% of the volume of international trade in goods is carried by sea, a percentage that is greater for developing countries.

However, the maritime trade system has shown itself to be extremely vulnerable to disruption, which impacts its operations and leads to shortages of vital goods across the globe. These disturbances continue — and are likely to worsen in the future. To thrive moving forward, countries need to better manage risk and focus on resilience. Recent, ongoing, and future disruptions are linked to five key causes: (1) COVID-19 pandemic, (2) current geopolitical conflict, (3) emerging geopolitical tensions, (4) climate change, and (5) human/technology factors.

1. COVID-19 pandemic

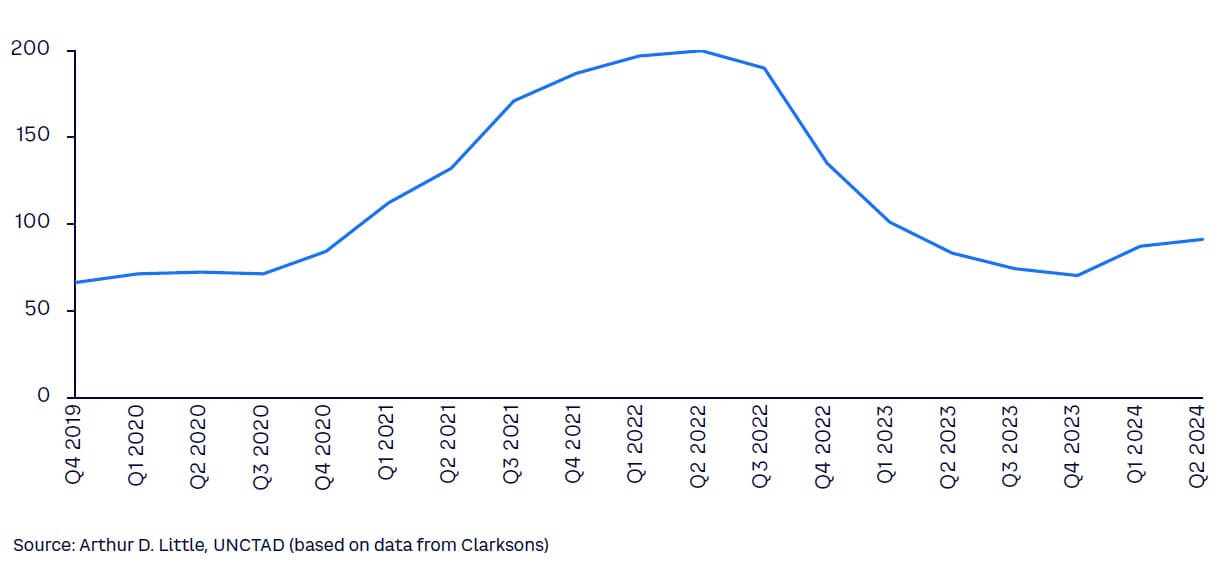

COVID-19 caused significant disruptions to trade volumes, shipping prices, and the availability of containers and ships. In turn, this caused bottlenecks in global trade and the post-pandemic movement of goods, as shipping companies struggled to meet the surge in demand for goods once economies began to reopen. A significant increase in shipping prices resulted, with the Container Trades Statistics (CTS) average global container price index reaching record highs in Q2 2022, as shown in Figure 1. These rising prices highlighted the weaknesses of global supply chains and affected various industries (e.g., automotive) due to shortages of semiconductors, electronics, and retail.

2. Current geopolitical conflicts

Though global maritime supply chains recovered from COVID-19, the impacts of the Russia-Ukraine conflict and civil war in Yemen have significantly affected the sector. Ukraine’s agricultural exports have been disrupted substantially. Container shipping through the Red Sea declined by approximately 90% between December 2023 and mid-February 2024, according to the US Defense Intelligence Agency, as companies rerouted vessels due to Yemeni Houthi rebel attacks.

3. Emerging geopolitical tensions

Other critical trade routes face potential threats from geopolitical instability. Around a fifth of global oil production volumes pass through the narrow Strait of Hormuz into the Arabian Sea, and tensions between Iran and the West have already disrupted trade. For example, in April 2024, Iran’s Revolutionary Guards seized MSC Aires, a 150,000-ton container ship. Territorial disputes in the South China Sea could also potentially impact critical shipping lanes that carry over US $5 trillion in annual trade.

4. Climate change

Climate change is increasing the number and unpredictability of extreme weather events, which impacts trade routes. In 2023, severe drought conditions in the Panama Canal, which accounts for 2.5% of all global maritime trade, led operators to regulate traffic flows, reducing tonnage transits by a third, according to maritime news site Splash247.com. Operations are unlikely to be fully back to normal until 2025.

5. Human & technology factors

Maritime trade relies on a combination of human skill and digital infrastructure. In 2021, human error caused the grounding of the Ever Given container ship in the Suez Canal, blocking the trade route for nearly a week and costing global trade between $6-$10 billion, as reported by insurer Allianz. Labor disputes, such as the recent US dockworkers strike, can also impact port operations and lead to delays. On the technology side, Maersk was forced to shut down and rebuild its entire IT infrastructure after being infected with WannaCry malware, leading to losses of over $300 million.

STRATEGIES TO OVERCOME DISRUPTION

The maritime industry has always been susceptible to the effects of the above issues. However, two factors dramatically increase risks for the sector. First, many of these challenges are happening simultaneously, such as attacks in the Red Sea and the partial closure of the Panama Canal, which limits alternative options for maritime trade, creates bottlenecks, and increases costs and journey times. Second, global supply chains are complex and interconnected, as shown by the long-term damage caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. “Just in time” logistics leave little margin for error around deliveries, meaning even small-scale issues can have outsize consequences. Given the growing risks posed by a volatile and unpredictable environment, how can countries safeguard vital supplies of raw materials, food, and energy?

Understanding current and future risks and taking preemptive action to increase resilience is vital and should focus on three main strategies: (1) analyzing vulnerabilities, (2) embracing alternative trade corridors, and (3) harnessing/analyzing data to enable effective rerouting.

1. Analyzing vulnerabilities

Governments need to understand how susceptible their economies are to breakdowns in global maritime trade. This requires them to examine two critical factors:

- Reliance on international trade. Countries that depend heavily on global markets for the import of essential goods or exports of their own products are clearly more susceptible to disruptions. The degree of reliance can be calculated by measuring the percentage of a country’s GDP derived from trade, based on validated data from organizations (e.g., World Bank or OECD).

- Vulnerability to trade disruptions. Countries located near conflict zones or that rely on known trade chokepoints (e.g., the Strait of Hormuz) are at greater risk if political tensions rise, war breaks out, or attacks that disrupt maritime trade multiply.

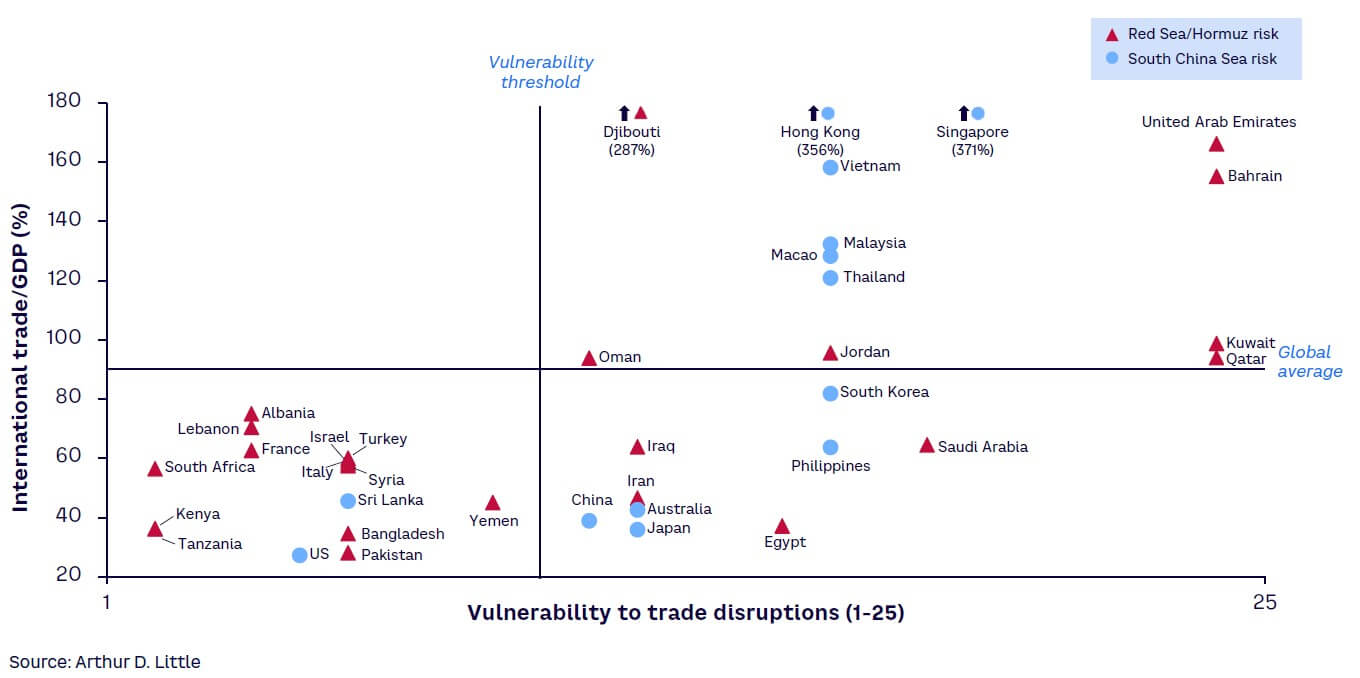

To analyze these risks, Arthur D. Little (ADL) developed a vulnerability matrix (see Figure 2). This involves calculating the average percentage of international trade’s impact on GDP for each named country over a 10-year period (2013–2022), focusing on those where trade constitutes at least 30% of GDP and the economy is significant. The analysis also estimates an index of the country’s exposure to trade disruption risk based on:

- A qualitative (1-5) index of the country’s exposure to areas seeing major current/potential geopolitical disruptions (e.g., the Red Sea, Strait of Hormuz, and South China Sea)

- A qualitative (1-5) index of the country’s ability to access alternative sea or land routes, which could help offset potential disruption

Multiplying these two factors provides an index of 1-25, representing each country’s vulnerability to trade disruptions, with 25 being the most vulnerable. Figure 2 focuses on selected countries; others will likely be impacted. For example, if large container ships do not transit through the Suez Canal, their new routes bypass Italy, reducing that country’s trans-shipment volumes.

Countries are then plotted on the vulnerability matrix based on two axes: (1) the percentage of GDP linked to international trade and (2) their exposure to trade disruptions. This visualization allows countries to understand their position in terms of risk.

Countries on the right-hand side of the matrix, which are more vulnerable, should act immediately to create a strategy to mitigate disruption potential. Actions within this strategy include increasing focus on infrastructure investment, developing new trade corridors, boosting national supply chain resilience, and considering diversifying suppliers or stockpiling essential goods. While less vulnerable, countries on the matrix’s left-hand side should still prepare for potential disruptions and invest in long-term infrastructure and alternative trade routes. For example, the COVID crisis demonstrated the need for immediate, local access to essential goods, such as protective masks, across all countries.

The vulnerability matrix provides a strategic tool for governments to prioritize investments, infrastructure development, and policy decisions to mitigate trade risks. It also helps businesses operating in these countries make informed choices about their supply chains, encouraging strategies such as diversifying suppliers, nearshoring production, or exploring alternative transportation methods to protect against disruptions.

2. Embracing alternative trade corridors

Figures from UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD) show that just two trade routes (Suez and Trans-Pacific) handle around 40% of global trade. This means that any issues with one or both will have an outsize impact on the global economy — and the individual countries that rely on specific routes. Because weaknesses exist in all major trade corridors, countries need to mitigate risk by investigating and establishing alternatives to reduce the threat of issues at critical chokepoints and single points of failure. Developing alternatives can take time and significant investment, so decisions must be made now to safeguard future economic prosperity.

Alternative trade corridors deliver three major benefits:

- Enhanced resilience. A network of alternative trade corridors provides greater flexibility in routing cargo around disruptions caused by geopolitical tensions, accidents, or natural disasters. This diversification reduces the impact of any single event on the global flow of goods, although it can lengthen transport distances.

- Reduced congestion. By spreading trade flows across multiple corridors, alternative routes can help alleviate congestion on heavily utilized waterways like the Suez Canal and the Strait of Hormuz. This can improve efficiency, reduce time spent waiting for transit, lower transportation costs, and shorten journey times.

- Economic development. Developing new trade corridors, including the creation of ports and rail networks, can stimulate economic activity in previously underdeveloped regions. This creates new investment opportunities, jobs, and infrastructure improvements along these routes.

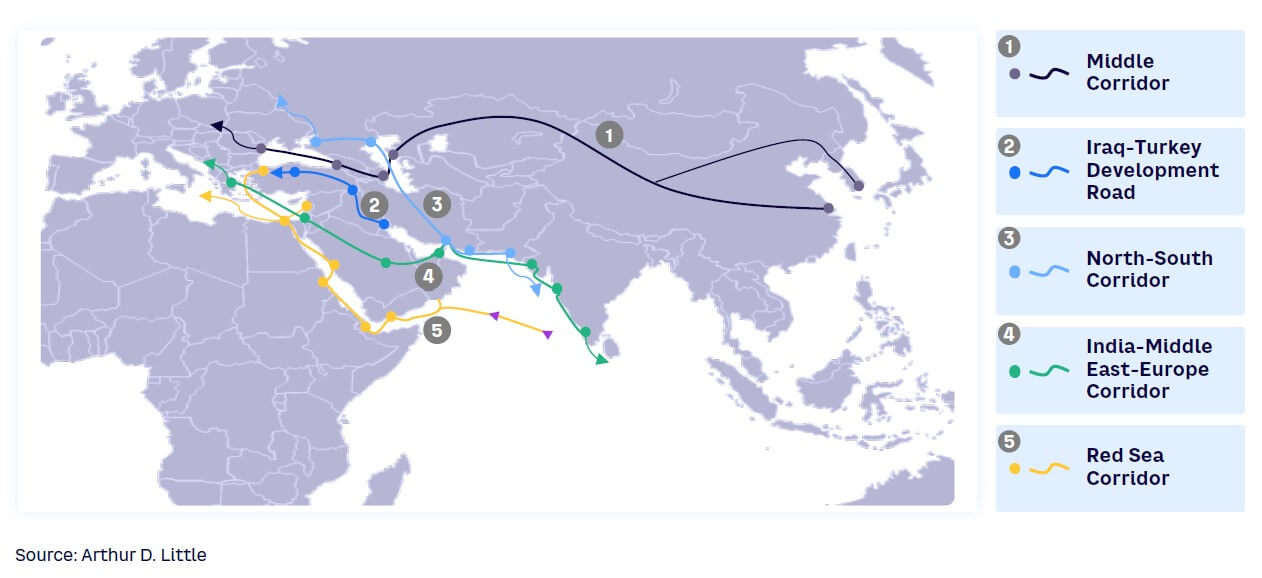

A range of alternative trade corridors that bypass the Red Sea and the Strait of Hormuz are actively being planned or implemented (see Figure 3). Each of these corridors aims to reduce reliance on congested or unprotected maritime routes, improve efficiency, and stimulate economic development in the regions they cross.

- The Middle Corridor (or Trans-Caspian International Transport Route) connects China and Europe through Central Asia, using a combination of rail and sea transport, offering a faster and cheaper alternative to traditional routes like the Suez Canal.

- The Iraq-Turkey Development Road will link Basra, Iraq, to Ovaköy, Türkiye, via rail and road and provide faster access to Europe, bypassing the Suez Canal and reducing reliance on maritime routes. The initial phase of the project should be completed by 2028.

- The North-South Transport Corridor aims to connect landlocked Central Asian countries with ports on the Indian Ocean through Iran and provide a shorter route between India and Russia. Parts of the route have been completed, but it is not yet fully operationalized.

- The India-Middle East-Europe Corridor proposes to connect India to Europe through the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), Israel, and Greece. It bypasses the Suez Canal and aims to increase economic integration between Asia, countries in the Gulf, and Europe. Participating countries signed a memorandum of understanding around the project in September 2023.

3. Harnessing & analyzing data to enable effective rerouting

To successfully manage their maritime trade flows, countries need to understand the impact of current and future disruptions and act quickly to embrace alternatives to safeguard supply chains, while investing strategically in the most effective alternative trade corridors for their economies.

This requires data-driven decision-making, enabled by tools such as ADL’s supply chain resilience model, which can analyze potential disruptions to identify the most efficient alternative route (in terms of both time and cost) for specific cargo types. ADL has successfully used this tool with a national port authority, customized around its specific needs, to cover:

- Five different potential operational disruptions (three local and two regional)

- Three cargo rerouting scenarios (to reroute solely emergency goods, strategic goods, or 100% of all goods imported/exported)

- The ability to remove each type of infrastructure analyzed (ports, railways, highways, airports)

- Four cargo types (container, dry bulk, general cargo, liquid cargo)

- Two types of cargo flows (import and import/export)

For these scenarios, the model identified the optimal rerouting option based on minimizing logistics costs and simulating the redirection of cargo volumes until the rerouting option’s spare capacity was fully utilized.

Countries should also use data on trade volumes, future growth projections, and potential chokepoints to guide investment in infrastructure development and help steer potential international collaborations to maximize the chances of success.

Relying on data delivers two clear benefits:

- Improving risk management. Countries can manage the risk of maritime trade issues on their economy, prepare countermeasures, and invest in strengthening national resilience.

- Driving targeted investments. Analysis can highlight strategic gaps and opportunities where countries, directly or through national champions, should invest to potentially benefit from future actions, such as creating their own alternative infrastructure or trade routes.

By understanding and addressing vulnerabilities, exploring alternative trade corridors, and making data-driven investments, countries and businesses can work toward building a more resilient and diversified global trade network. This will help ensure the smooth flow of goods in the face of future disruptions, contributing to more stable and prosperous national — and global — economies.

Conclusion

INCREASING RESILIENCE TO MARITIME TRADE DISRUPTIONS

Recent issues that have impacted maritime trade, from the pandemic to conflicts, are not isolated events and demonstrate that risks are increasing over time. Countries therefore need to focus on becoming more resilient to safeguard their economic and social well-being through a combination of the following:

- Understanding their level of risk and how it impacts their economy/infrastructure and taking preemptive measures to mitigate vulnerabilities, including addressing the impacts of climate change on trade routes

- Seizing new opportunities as trade patterns potentially shift by developing alternative trade corridors and new trade infrastructure, collaborating internationally to strengthen networks and influence

- Adopting a more proactive strategy that uses data to guide risk-reducing investment decisions and simulate potential alternative scenarios, enabling timely corrective actions and strengthening of national resilience