DOWNLOAD

11 min read

Chemicals: The old normal or the new normal?

Given its central position to the global economy, the chemical sector has felt the full force of COVID-19, though some players have suffered more than others. We analyze who the winners and losers currently are, and focus on the steps that all chemical companies need to take now to seize future opportunities – rethinking their purposes, promises and portfolios to drive future growth, value creation and resilience.

Never before in human history have so many regions shut down large parts of their economies in near synchronization. As essential parts of every economy, chemicals and materials are present in everyday-life products, which heavily exposes the sector to this broader market stagnation.

This article will explore how the sector has coped in the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis, highlighting noticeable actions taken by individual players and analyzing potential directions for the industry’s future. We strongly believe that, alongside the issues it brings, the crisis offers a great opportunity for chemical and material players to speed up their transformational initiatives and, once again, be seen as an essential solution-providing industry that benefits us all.

This article will explore how the sector has coped in the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis, highlighting noticeable actions taken by individual players and analyzing potential directions for the industry’s future. We strongly believe that, alongside the issues it brings, the crisis offers a great opportunity for chemical and material players to speed up their transformational initiatives and, once again, be seen as an essential solution-providing industry that benefits us all.

The impact of COVID-19 on the chemical industry so far

Market impact

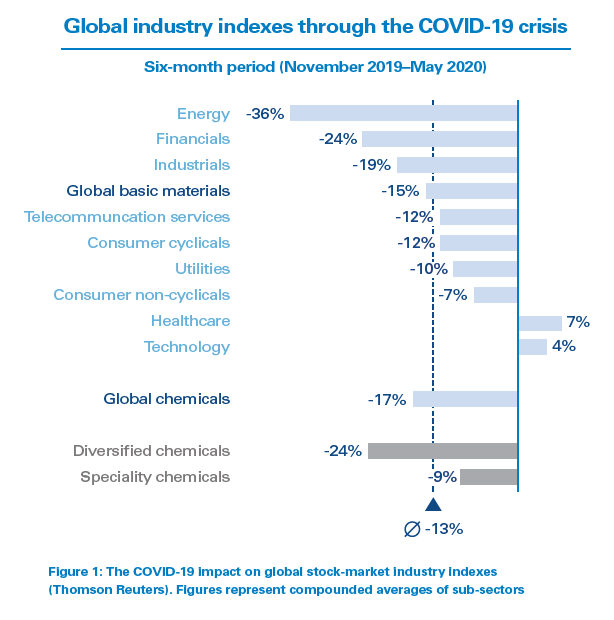

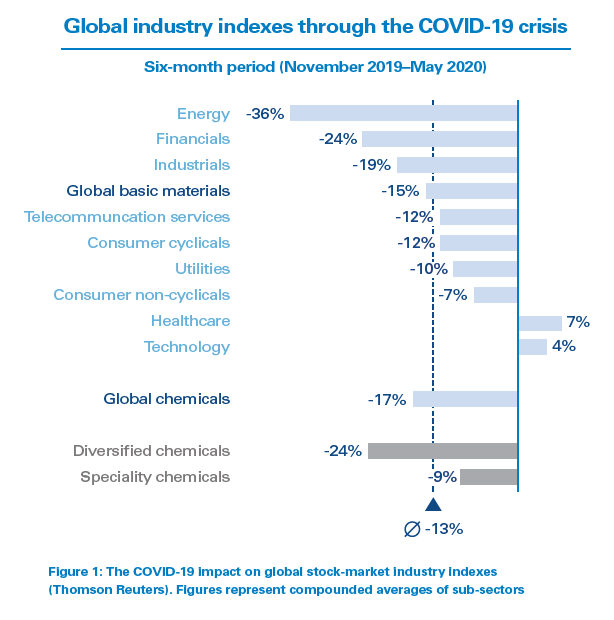

The global stock market is effectively a machine for digesting complex information and outlining the consequences for businesses and sectors. Reviewing its conclusions in terms of share-price fluctuations therefore provides interesting insights into how different industries have coped, or are expected to cope, with the crisis. Our analysis is based on a six-month time frame, incorporating the three months leading up to the crisis (a pre-crisis baseline) and the initial three months of the crisis itself (providing a full time span to show the resiliency of different industries, sectors, and players).

Our analysis in Figure 1 shows that:

- The global Materials/Chemicals sectors suffered significantly (an approximate -15 percent market return) in the midst of the crisis.

- This was not as poor a performance as achieved by the Energy sector, which was even more exposed to the contraction in the oil price, or Financial services, which was heavily exposed to the negative-balance-sheet consequences of the crisis.

- Healthcare led the recovery (which was unsurprising, given its prominent role in this crisis), followed by Technology, which showed that investors were rapid and eager to reinvest proceeds in expected highgrowth areas.

- There was a striking difference in returns between the diversified (-24 percent) and specialty (-9 percent) Chemicals sub-sectors. One reason for this gap was the higher exposure of diversified providers to low oil prices and the broader market downturn in demand, which made them less resilient to the crisis’s impact.

Operational impact

As with other companies, chemical corporations are adapting their core operations in three different ways:

- Speeding up digitization efforts: Social-distancing rules made this compulsory – corporations from many sectors were forced to suddenly shift towards collaborative virtual work environments. For office/ management workers, this is relatively simple to achieve, and although true lights-out manufacturing is not yet in place, chemical companies have heavily automated production over the last decade. More difficult are those activities that have historically depended on physical proximity: meeting new people, exchanging ideas, and of course, advocating, convincing and negotiation. These are all essential components of commercial and R&D/innovation functions – unless travel restrictions are lifted soon, companies will need to find solutions that go beyond simply doing video calls.

- Adapting production lines: The needs of the crisis have led many chemical firms to adapt to meet the sudden huge demand for a wide variety of medical disposables and protective gear. Producers such as 3M and Braskem have stepped up production of their existing core products overnight to supply face masks and materials for protective gear, accomplishing in weeks what normally would take many months. Others have switched their existing production lines to manufacture products not in their conventional portfolios. Many, such as Arkema, Givaudan and Henkel, turned to production of hand sanitizers, whereas some joined forces to produce masks, such as DSM and Dutch mattress maker Auping. However, not all of these initiatives are expected to have longer-term strategic impact.

Another category of solutions that has emerged that may be more long lasting involves the many 3D-printing initiatives set up, mainly to produce PPE materials. Solvay, HP and Stratasys are good examples, as is the army of distributed DIY producers that have jumped on this opportunity. - De-risking the supply chain: Reminiscent of the 2011 Fukushima disaster in Japan, the COVID-19 crisis has made many worry about major global supply-chain disruptions. There have been temporary disturbances caused by surging demand (such as for non-woven materials used in face masks), with the overall consequences relatively modest. But many business leaders see a pattern emerging after recent threats of trade wars and regard the pandemic as a further warning signal not to be over-reliant on remote, concentrated, and possibly erratic supply chains.

Company impact: Are there winners and losers?

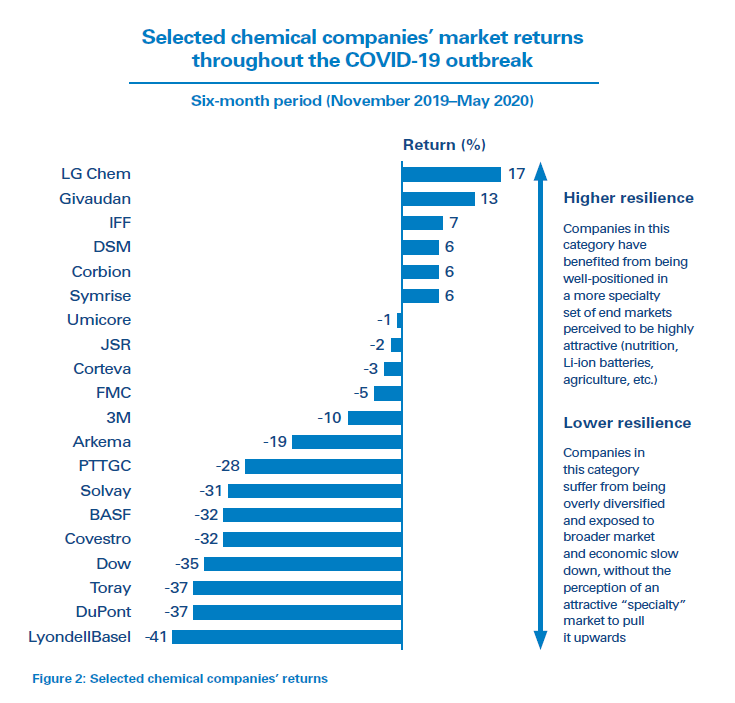

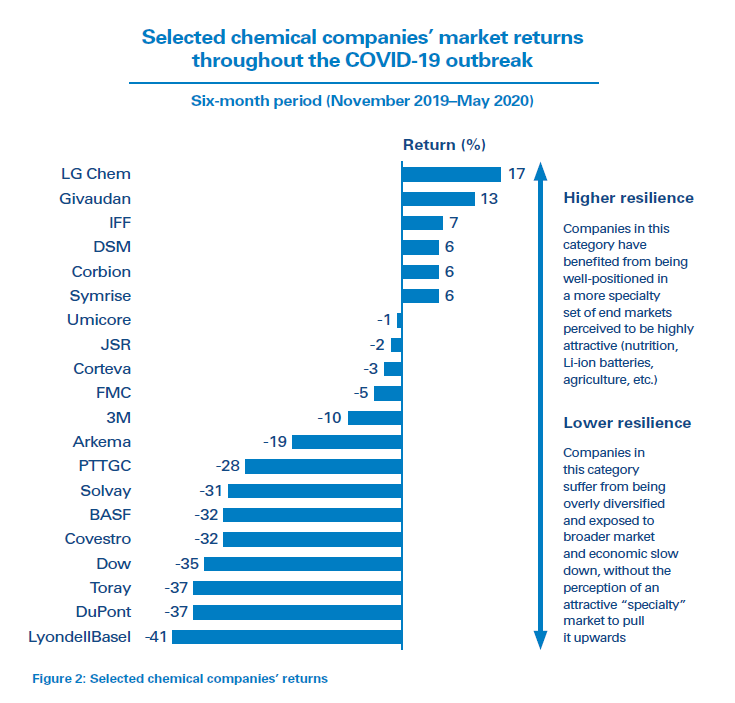

The chemical industry serves a wide range of end markets, some of which have been badly affected, such as automotive and aerospace, and others that have expanded (e.g., medical disposables and packaged consumer goods). To find out which types of players are proving most resilient, we analyzed the immediate post-shock market returns of a selected group of chemical companies. Our findings (Figure 2) show very different recovery dynamics between selected players, largely depending on the inherent growth promise of their overall business portfolios.

- “High-resilience” players: These are companies that have so far exhibited roughly stable and/or positive recoveries – it is remarkable that a few players, even while still in the midst of the crisis, could register double-digit returns. We believe the reason for such resilience lies in their perceived higher level of exposure to more attractive markets. Nutrition (DSM, Corbion, Givaudan, Symrise, IFF) is a clear winner, as supermarkets were almost the only businesses which remained open during the early days of the crisis, together with the emerging EV market (LG Chem, Umicore). Agricultural players (FMC, Corteva) are in the middle of the increasingly resilient pack, joined by JSR, which represents examples of exposure to selective specialty niches such as healthcare and technology, including life sciences diagnostics, personal care, semiconductor materials and crop protection.

- “Low-resilience” players: These are companies that have been much more severely affected by the crisis thus far, evidenced by falling share prices and collapsing profitability levels. For behemoth BASF, this can mostly be attributed to its sheer size (“when the tide recedes, all boats go down”), while others seem overly exposed to non-differentiated petrochemicals (e.g., LyondellBasel) or faltering end markets such as aviation and automotive (Solvay and Covestro).

As we argued in our 2019 report, “Breaking the mold”, this matters not just financially but, in the absence of a credible narrative for future growth, also strategically. Many companies in this category can currently do little more than work towards recovery, while more resilient players are able to invest and strengthen their positions.

Recovery and growth in the chemicals industry: Never waste a good crisis?

Looking back to the 2008 financial crisis, the current speak about the “new normal” sounds all too familiar. As we outlined in our “Breaking the mold” report, at that point the chemical industry was relatively quick to recover, but then mostly carried on with its “old normal” ways of working. We argued that even under favorable economic conditions, such a “more-of-the-same” strategy would eventually lead to missed opportunities and value destruction for most chemical firms. Instead, they should seize the potential of technology and industry convergence, applying new business models and approaches to developing and delivering solutions to the most pressing needs. We still maintain this position and believe that the initial impact of the crisis (Figure 2) reinforces our point.

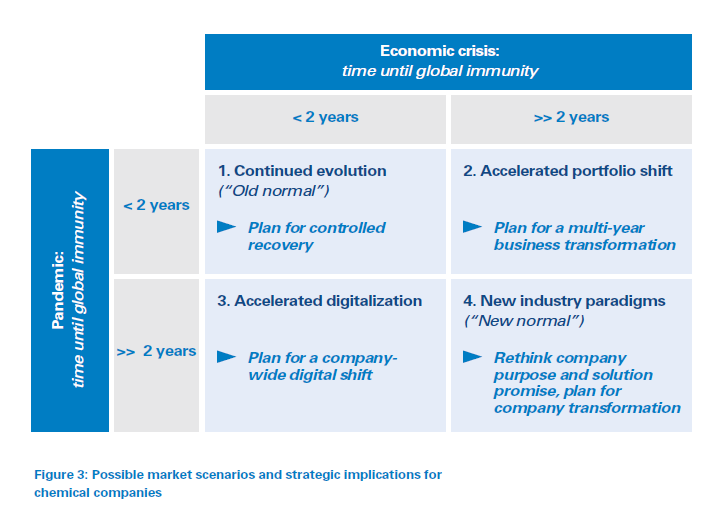

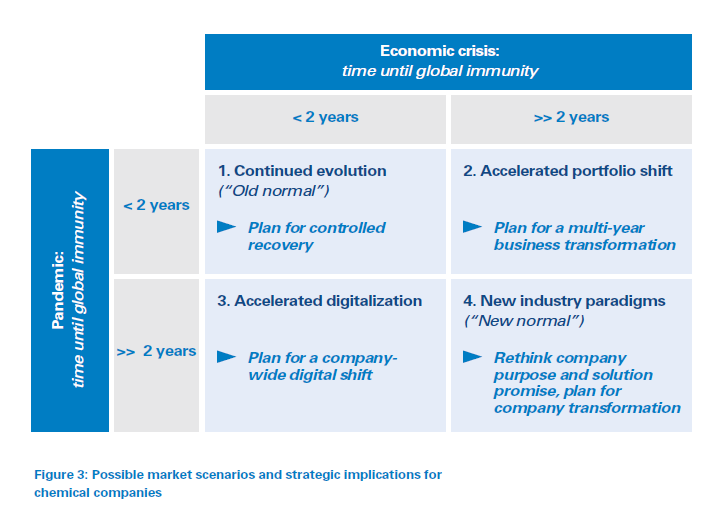

At the same time, the chemical executives we spoke to while preparing this article all agreed that it was too early to tell whether 2020 would become the turning point that failed to happen post-2008. What is clear is that this will depend on both the time taken for pandemic restrictions to be removed entirely, and the extent of the economic crisis that is already ensuing. These two dimensions are, of course, not entirely independent because a longer pandemic will probably prolong the recession. However, we believe there could still be a longer pandemic and a shorter recession, and vice versa: some countries may be better at keeping infection rates at bay than others, and highly digitalized economies and companies may go a long way towards making the “90 percent economy” work.

So how might the current crisis be different from that of 2008?

- Firstly, the recession could be much more prolonged and steeper. Back then it took roughly two years before companies could shift from “damage control” to “build and grow” strategies – this time it could be much longer.

- Secondly, it could take about the same amount of time before business activities such as unencumbered faceto- face meetings and traveling are back to normal – something that will probably require broad availability of effective vaccines.

Combining these two major uncertainties leaves us with four scenarios (Figure 3):

1. Continued evolution: As past crises have shown, the death of the “old normal” tends to be announced prematurely, and the current crisis may be no exception. Companies planning for this scenario are focusing predominantly on “do anyway” activities: adapting operations and ways of working, planning for low-risk operational rampups, and reviewing the impact on the current strategic outlook. Already, many companies are investing in more holistic and data-driven risk management and decisionmaking. Additionally, they may be moving ahead with more distributed production facilities and supplier bases to improve resilience to future shocks.

It should be clear, however, that following a “do nothing” course focused on a pre-COVID-19 status quo is, in itself, a strategic decision, and a risky one at that. Firstly, there is mounting evidence that the world is heading for a very different outcome (see below), and secondly, the old normal was hardly an attractive one for many chemical companies.

2. Accelerated portfolio shift: With a swift return to normal ways of working but a prolonged and steep recession, many companies and shareholders will see the inevitability of making fundamental portfolio decisions. High-resilience companies (Figure 2) will take advantage of their relatively unscathed performance in M&A, partnering and new business development. Companies that are less resilient will face stark choices between going for “commodity scale” or “solutions scope”. Of course, diversification involves a lot more than redrawing the future business portfolio on a whiteboard. From decades of experience accompanying clients on this journey, we identify two major factors for success, among many:

- Firstly, overall innovation models need to move away from being essentially support functions created to optimize asset productivity, towards becoming truly strategic business functions for sizable and reliable away-from-the-core innovation that effectively target attractive growth fields.

- Secondly, on the organizational side, companies need to move into an “ambidextrous” set-up that allows them to still excel at performance at scale while simultaneously delivering speed and creativity. They need the agility of a small start-up but the resources of a corporation.

3. Accelerated digitalization: Alternatively, the world may quickly go back to a “90 percent economy”, which would allow many end markets and business processes to become at least stable and manageable, albeit with lackluster growth and profitability. But from a business perspective, the 10 percent that remained impeded (such as safety and quality control, ideation and consultative selling) would force chemical firms to find and implement digital solutions at a rapid pace.

4. New paradigms: A prolonged period of lockdowns, travel restrictions and business contraction will most likely lead to a chemical industry that looks markedly different from that of today. Big shifts in demand and depressed commodity margins will remain prevalent for many years, which means maintaining the status quo will be increasingly unattractive, except to those with superior cost and/or scale advantages. The others will need to undertake fundamental revisions of their narratives for future growth and value creation, and ultimately of their business portfolios and core competencies. The good news, compared to 2008, is that shareholders are likely to be more receptive to such strategic investments, especially while the overall cost of capital is low.

Insight for the executive

The chemical industry has lived through many crises before, and it will survive the current one. Those who believe we have reached some point of singularity in which none of the old rules apply should think back 12 years, when the unimaginable also became a daily headline. With most economists, epidemiologists and politicians still so much in the dark about the future, business leaders can only turn to scenario-based decision-making and planning, and ensure that they will be able to react quickly to new developments. However, as Figure 3 shows, there are a number of common themes in all scenarios that should be “no regret” recommendations to chemical executives for this year and next:

- Invest in forward-looking capabilities, quick decisionmaking and more resilient operations – you will need these in any conceivable scenario. Many chemical executives have reported that their current intelligence and decision-making are still bureaucratic and “analogue” affairs.

- Coordinate and accelerate the numerous digitalization initiatives in your company, particularly in customerfacing processes and end-to-end innovation. (See also our article on the laboratory of the future.) Although everyone is implementing the “obvious” digital use cases (such as the IoT in production), actual differentiation will come from finding and implementing working digital solutions for seemingly exclusively interpersonal areas such as (chemical) solution selling or ideation.

- Perhaps most importantly, take advantage of the open mind-set that the current crisis has brought to every decision-maker around you: the cost of doing nothing, of maintaining the status quo, can no longer be casually assumed to be zero – as has so often been the case. Now is the time to seriously rethink your company’s purpose and solution promise, your future business portfolio, and the overall narrative behind future growth, value creation and resilience.

Given its central position to the global economy, the chemical sector has felt the full force of COVID-19, though some players have suffered more than others. We analyze who the winners and losers currently are, and focus on the steps that all chemical companies need to take now to seize future opportunities – rethinking their purposes, promises and portfolios to drive future growth, value creation and resilience.

Never before in human history have so many regions shut down large parts of their economies in near synchronization. As essential parts of every economy, chemicals and materials are present in everyday-life products, which heavily exposes the sector to this broader market stagnation.

This article will explore how the sector has coped in the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis, highlighting noticeable actions taken by individual players and analyzing potential directions for the industry’s future. We strongly believe that, alongside the issues it brings, the crisis offers a great opportunity for chemical and material players to speed up their transformational initiatives and, once again, be seen as an essential solution-providing industry that benefits us all.

This article will explore how the sector has coped in the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis, highlighting noticeable actions taken by individual players and analyzing potential directions for the industry’s future. We strongly believe that, alongside the issues it brings, the crisis offers a great opportunity for chemical and material players to speed up their transformational initiatives and, once again, be seen as an essential solution-providing industry that benefits us all.

The impact of COVID-19 on the chemical industry so far

Market impact

The global stock market is effectively a machine for digesting complex information and outlining the consequences for businesses and sectors. Reviewing its conclusions in terms of share-price fluctuations therefore provides interesting insights into how different industries have coped, or are expected to cope, with the crisis. Our analysis is based on a six-month time frame, incorporating the three months leading up to the crisis (a pre-crisis baseline) and the initial three months of the crisis itself (providing a full time span to show the resiliency of different industries, sectors, and players).

Our analysis in Figure 1 shows that:

- The global Materials/Chemicals sectors suffered significantly (an approximate -15 percent market return) in the midst of the crisis.

- This was not as poor a performance as achieved by the Energy sector, which was even more exposed to the contraction in the oil price, or Financial services, which was heavily exposed to the negative-balance-sheet consequences of the crisis.

- Healthcare led the recovery (which was unsurprising, given its prominent role in this crisis), followed by Technology, which showed that investors were rapid and eager to reinvest proceeds in expected highgrowth areas.

- There was a striking difference in returns between the diversified (-24 percent) and specialty (-9 percent) Chemicals sub-sectors. One reason for this gap was the higher exposure of diversified providers to low oil prices and the broader market downturn in demand, which made them less resilient to the crisis’s impact.

Operational impact

As with other companies, chemical corporations are adapting their core operations in three different ways:

- Speeding up digitization efforts: Social-distancing rules made this compulsory – corporations from many sectors were forced to suddenly shift towards collaborative virtual work environments. For office/ management workers, this is relatively simple to achieve, and although true lights-out manufacturing is not yet in place, chemical companies have heavily automated production over the last decade. More difficult are those activities that have historically depended on physical proximity: meeting new people, exchanging ideas, and of course, advocating, convincing and negotiation. These are all essential components of commercial and R&D/innovation functions – unless travel restrictions are lifted soon, companies will need to find solutions that go beyond simply doing video calls.

- Adapting production lines: The needs of the crisis have led many chemical firms to adapt to meet the sudden huge demand for a wide variety of medical disposables and protective gear. Producers such as 3M and Braskem have stepped up production of their existing core products overnight to supply face masks and materials for protective gear, accomplishing in weeks what normally would take many months. Others have switched their existing production lines to manufacture products not in their conventional portfolios. Many, such as Arkema, Givaudan and Henkel, turned to production of hand sanitizers, whereas some joined forces to produce masks, such as DSM and Dutch mattress maker Auping. However, not all of these initiatives are expected to have longer-term strategic impact.

Another category of solutions that has emerged that may be more long lasting involves the many 3D-printing initiatives set up, mainly to produce PPE materials. Solvay, HP and Stratasys are good examples, as is the army of distributed DIY producers that have jumped on this opportunity. - De-risking the supply chain: Reminiscent of the 2011 Fukushima disaster in Japan, the COVID-19 crisis has made many worry about major global supply-chain disruptions. There have been temporary disturbances caused by surging demand (such as for non-woven materials used in face masks), with the overall consequences relatively modest. But many business leaders see a pattern emerging after recent threats of trade wars and regard the pandemic as a further warning signal not to be over-reliant on remote, concentrated, and possibly erratic supply chains.

Company impact: Are there winners and losers?

The chemical industry serves a wide range of end markets, some of which have been badly affected, such as automotive and aerospace, and others that have expanded (e.g., medical disposables and packaged consumer goods). To find out which types of players are proving most resilient, we analyzed the immediate post-shock market returns of a selected group of chemical companies. Our findings (Figure 2) show very different recovery dynamics between selected players, largely depending on the inherent growth promise of their overall business portfolios.

- “High-resilience” players: These are companies that have so far exhibited roughly stable and/or positive recoveries – it is remarkable that a few players, even while still in the midst of the crisis, could register double-digit returns. We believe the reason for such resilience lies in their perceived higher level of exposure to more attractive markets. Nutrition (DSM, Corbion, Givaudan, Symrise, IFF) is a clear winner, as supermarkets were almost the only businesses which remained open during the early days of the crisis, together with the emerging EV market (LG Chem, Umicore). Agricultural players (FMC, Corteva) are in the middle of the increasingly resilient pack, joined by JSR, which represents examples of exposure to selective specialty niches such as healthcare and technology, including life sciences diagnostics, personal care, semiconductor materials and crop protection.

- “Low-resilience” players: These are companies that have been much more severely affected by the crisis thus far, evidenced by falling share prices and collapsing profitability levels. For behemoth BASF, this can mostly be attributed to its sheer size (“when the tide recedes, all boats go down”), while others seem overly exposed to non-differentiated petrochemicals (e.g., LyondellBasel) or faltering end markets such as aviation and automotive (Solvay and Covestro).

As we argued in our 2019 report, “Breaking the mold”, this matters not just financially but, in the absence of a credible narrative for future growth, also strategically. Many companies in this category can currently do little more than work towards recovery, while more resilient players are able to invest and strengthen their positions.

Recovery and growth in the chemicals industry: Never waste a good crisis?

Looking back to the 2008 financial crisis, the current speak about the “new normal” sounds all too familiar. As we outlined in our “Breaking the mold” report, at that point the chemical industry was relatively quick to recover, but then mostly carried on with its “old normal” ways of working. We argued that even under favorable economic conditions, such a “more-of-the-same” strategy would eventually lead to missed opportunities and value destruction for most chemical firms. Instead, they should seize the potential of technology and industry convergence, applying new business models and approaches to developing and delivering solutions to the most pressing needs. We still maintain this position and believe that the initial impact of the crisis (Figure 2) reinforces our point.

At the same time, the chemical executives we spoke to while preparing this article all agreed that it was too early to tell whether 2020 would become the turning point that failed to happen post-2008. What is clear is that this will depend on both the time taken for pandemic restrictions to be removed entirely, and the extent of the economic crisis that is already ensuing. These two dimensions are, of course, not entirely independent because a longer pandemic will probably prolong the recession. However, we believe there could still be a longer pandemic and a shorter recession, and vice versa: some countries may be better at keeping infection rates at bay than others, and highly digitalized economies and companies may go a long way towards making the “90 percent economy” work.

So how might the current crisis be different from that of 2008?

- Firstly, the recession could be much more prolonged and steeper. Back then it took roughly two years before companies could shift from “damage control” to “build and grow” strategies – this time it could be much longer.

- Secondly, it could take about the same amount of time before business activities such as unencumbered faceto- face meetings and traveling are back to normal – something that will probably require broad availability of effective vaccines.

Combining these two major uncertainties leaves us with four scenarios (Figure 3):

1. Continued evolution: As past crises have shown, the death of the “old normal” tends to be announced prematurely, and the current crisis may be no exception. Companies planning for this scenario are focusing predominantly on “do anyway” activities: adapting operations and ways of working, planning for low-risk operational rampups, and reviewing the impact on the current strategic outlook. Already, many companies are investing in more holistic and data-driven risk management and decisionmaking. Additionally, they may be moving ahead with more distributed production facilities and supplier bases to improve resilience to future shocks.

It should be clear, however, that following a “do nothing” course focused on a pre-COVID-19 status quo is, in itself, a strategic decision, and a risky one at that. Firstly, there is mounting evidence that the world is heading for a very different outcome (see below), and secondly, the old normal was hardly an attractive one for many chemical companies.

2. Accelerated portfolio shift: With a swift return to normal ways of working but a prolonged and steep recession, many companies and shareholders will see the inevitability of making fundamental portfolio decisions. High-resilience companies (Figure 2) will take advantage of their relatively unscathed performance in M&A, partnering and new business development. Companies that are less resilient will face stark choices between going for “commodity scale” or “solutions scope”. Of course, diversification involves a lot more than redrawing the future business portfolio on a whiteboard. From decades of experience accompanying clients on this journey, we identify two major factors for success, among many:

- Firstly, overall innovation models need to move away from being essentially support functions created to optimize asset productivity, towards becoming truly strategic business functions for sizable and reliable away-from-the-core innovation that effectively target attractive growth fields.

- Secondly, on the organizational side, companies need to move into an “ambidextrous” set-up that allows them to still excel at performance at scale while simultaneously delivering speed and creativity. They need the agility of a small start-up but the resources of a corporation.

3. Accelerated digitalization: Alternatively, the world may quickly go back to a “90 percent economy”, which would allow many end markets and business processes to become at least stable and manageable, albeit with lackluster growth and profitability. But from a business perspective, the 10 percent that remained impeded (such as safety and quality control, ideation and consultative selling) would force chemical firms to find and implement digital solutions at a rapid pace.

4. New paradigms: A prolonged period of lockdowns, travel restrictions and business contraction will most likely lead to a chemical industry that looks markedly different from that of today. Big shifts in demand and depressed commodity margins will remain prevalent for many years, which means maintaining the status quo will be increasingly unattractive, except to those with superior cost and/or scale advantages. The others will need to undertake fundamental revisions of their narratives for future growth and value creation, and ultimately of their business portfolios and core competencies. The good news, compared to 2008, is that shareholders are likely to be more receptive to such strategic investments, especially while the overall cost of capital is low.

Insight for the executive

The chemical industry has lived through many crises before, and it will survive the current one. Those who believe we have reached some point of singularity in which none of the old rules apply should think back 12 years, when the unimaginable also became a daily headline. With most economists, epidemiologists and politicians still so much in the dark about the future, business leaders can only turn to scenario-based decision-making and planning, and ensure that they will be able to react quickly to new developments. However, as Figure 3 shows, there are a number of common themes in all scenarios that should be “no regret” recommendations to chemical executives for this year and next:

- Invest in forward-looking capabilities, quick decisionmaking and more resilient operations – you will need these in any conceivable scenario. Many chemical executives have reported that their current intelligence and decision-making are still bureaucratic and “analogue” affairs.

- Coordinate and accelerate the numerous digitalization initiatives in your company, particularly in customerfacing processes and end-to-end innovation. (See also our article on the laboratory of the future.) Although everyone is implementing the “obvious” digital use cases (such as the IoT in production), actual differentiation will come from finding and implementing working digital solutions for seemingly exclusively interpersonal areas such as (chemical) solution selling or ideation.

- Perhaps most importantly, take advantage of the open mind-set that the current crisis has brought to every decision-maker around you: the cost of doing nothing, of maintaining the status quo, can no longer be casually assumed to be zero – as has so often been the case. Now is the time to seriously rethink your company’s purpose and solution promise, your future business portfolio, and the overall narrative behind future growth, value creation and resilience.