DOWNLOAD

DATE

Contact

Long-haul (high-speed) rail has been gaining popularity globally in recent years – especially in Western Europe and East Asia. Due to the growing popularity among travelers and branching out of incumbent operators, it is likely that we will see diversification of business models in the near future. The airline industry saw such diversification in the late 1990s. Here, low-cost-carrier models have been particularly successful. Recently, the low-cost movement has also started to transform the coach industry. Could rail be next? First indications are shown by operators launching low-cost carrier models in France and Belgium and an unconventional player entering the market in Germany. This article examines the current status quo and outlines the low-cost carrier model as it is known in the aviation industry, before inspecting current low-cost models and evaluating whether spread is likely.

Status quo – Growing demand and rising popularity

With increasing mobility demand and evolving mobility needs, the transportation industry has drastically evolved from a single point-A-point-B routing system to interconnected networks encompassing road, rail and airways. Long-distance (crossregional) railway networks have especially flourished under this trend. As technological advancements allowed higher speeds and populations grew increasingly urban, long-distance passenger rail travel became an attractive mode of transport to invest in during the second half of the 20th century.

Today, governments are attracted to the high capacity and safety features, which can reduce traffic congestion, limit the strain on the environment and promote urban sprawl. Simultaneously, consumers (especially commuters) are attracted to potential time savings in door-to-door travel, as well as the comfort and freedom (free movement on board the train, possible entry and exit at every station). In Europe, the cross-border interconnectedness will be further extended by the development, expansion and integration of Trans-European Transport Networks and adoption of the new signaling standard and controlling system European Train Control System. European HSR track length will double – currently 11,100 km worth of track is in planning mode, compared to 9,200 km in operation and 1,700 km currently under construction (UIC, 2018).

Differentiating long-haul (high-speed) rail systems – Special tracks, signaling systems and rolling stock

Although long-haul trains are not necessarily synonymous with high speed, long-haul trains – at least for passenger travel – have only gained their popularity status by significantly reducing travel times between urban destinations. The common threshold which separates “normal” rolling stock from “high-speed” is 200 km per hour. The first system capable of this speed went operational in 1964 in Japan, with the 210 km-per-hour Shinkansen connecting Tokyo and Osaka. Today, (commercial) high-speed trains travel at speeds of up to 350 km per hour.

High-speed rail systems are independent train systems due to three requirements that classical train systems do not meet:

- Special tracks: High-speed tracks have different curvature and layout requirements from those of conventional tracks, as well as an ingenious power supply, including overhead lines/catenary and current collectors.

- Special signaling systems: In-cab instead of trackside signaling (unobservable at high speeds).

- Special rolling stock: Full train sets are required, rather than conventional train sets. These consist of locomotives and (passenger) cars, due to technical constraints (aerodynamics, power-to-weight ratio, safety features, etc.).

High-speed rail investments – Soaring capital expenditure

Extraordinary capital investments in track, stations and rolling stock are required. Even before the construction of tracks begins, the cost of land appropriation, environmental studies, and time required to reach political consensus accumulate to billions and years. Difficult topography and terrain requiring bridges or tunnels adds to the already-high cost of tracks. In Europe, the average cost per 1 km of track is 15–40 m € (UIC, 2018). Moreover, traditional train stations have to be reconstructed if they are to allow stoppage of rolling stock and increases in passenger traffic. Thus, investments usually occur on public rather than at private levels.

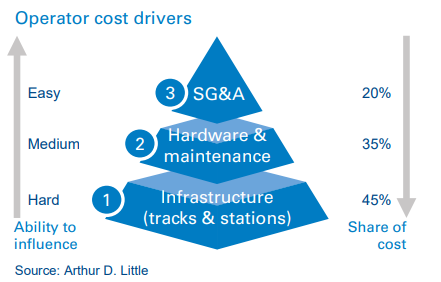

Cost drivers for operators – Inverse relationship between share of cost and ability to influence cost

To access railway infrastructure, operators buy licenses. In Germany, for example, track access costs 4+ €/km, and station access costs 5+ € per stop. This already balances a significant portion of the 28 €/km revenue (Bundesnetzagen-tur, 2016). New rolling stock costs approximately 35 m € for one 350-seat set, with maintenance costs of 5 percent (1.75 m €) per annum, assuming mileage of 500,000 km (UIC, 2017). The licenses and rolling stock result in two-thirds of all operator costs being fixed and independent from rolling stock load factor (travel volume).

The figure above illustrates the three cost drivers that train operators face – as well as their ability to influence these drivers; the relationship is inversely linked. The extent of influence on the largest cost driver, infrastructure, which makes up 45 percent of overall cost, is extremely limited. Operators must pay licensing fees for track and station access. The second-largest cost driver, hardware and maintenance, which makes up 35 percent of overall cost, can only be influenced to a certain degree. Operators can opt to use standardized, stripped-down trains, optimize efficiency and elongate usage times. Nonetheless, significant investments still have to be made. Ultimately, the smallest cost driver, selling, general and administrative costs, which makes up 20 percent of overall cost, can be influenced the most. Depending on how overheads are structured and employee labor conditions are set up, as well as the degree to which marketing and sales take place in a brick-and-mortar, click-and-mortar or pure-play environment has a significant effect on cost.

The French and Belgian cases – Minimize service, maximize convenience

Even though we have yet to see the same impact from low cost in rail as we have seen in aviation, first moves have been made. In France and Belgium, two operators have added the business model to their existing offering portfolios.

In 2013, France’s SNCF launched the low-cost brand Ouigo. Using standardized, older-model TGVs with a no-frills approach, it started servicing a route from Paris to the south of France. Since then, the brand has rapidly expanded and added new routes, and now services most major routes in the country.

In 2013, France’s SNCF launched the low-cost brand Ouigo. Using standardized, older-model TGVs with a no-frills approach, it started servicing a route from Paris to the south of France. Since then, the brand has rapidly expanded and added new routes, and now services most major routes in the country.

Ouigo services secondary train stations outside city centers and maximizes capacity in its rolling stock – just like LCCs in aviation. Trains are solely equipped with second-class seating, no buffet wagons and minimized storage space. Due to optimized departure and minimized turning times, as well as nighttime maintenance, the rolling stock covers twice as many kilometers as the TGV (Ouigo, 2017).

Further distinguishing features include:

- Operating in a closed system, which means access to and from trains is granted by a special ticketing check.

- Standard pricing is far below average TGV prices. Reservations, electrical sockets and large luggage allowances cost extra.

- Sales and customer service costs are kept to a minimum by conducting all activities over the internet.

- Labor costs are kept low by hiring young employees (lower HR costs) to perform a multitude of tasks and fulfill their statutory resting times in special resting rooms on board, rather than at destinations.

Fifty percent of customers switched from the classical TGV and SNCF plans, which increased Ouigo market share to 25 percent of its high-speed offering (SNCF, 2018).

In 2016, three years after the launch of Ouigo, Thalys started servicing the Brussels-Paris route using TGVs. Similar to Ouigo, it offers a no-frills service in capacitymaximized trains, employs little personnel, and conducts all sales activities via the internet. However, Izy differs from Ouigo in two aspects: (1) it services primary rather than secondary train stations at its destinations, and (2) routing is carried out on conventional, non-high-speed tracks. Thus, “normal” stop fees and lower track fees are incurred.

In 2016, three years after the launch of Ouigo, Thalys started servicing the Brussels-Paris route using TGVs. Similar to Ouigo, it offers a no-frills service in capacitymaximized trains, employs little personnel, and conducts all sales activities via the internet. However, Izy differs from Ouigo in two aspects: (1) it services primary rather than secondary train stations at its destinations, and (2) routing is carried out on conventional, non-high-speed tracks. Thus, “normal” stop fees and lower track fees are incurred.

According to Thalys’ CEO Annes Ogier:

All studies confirm that most people prefer the comfort and speed of Thalys to driving. We have a new solution. Reducing the speed and simplifying onboard service to a minimum enables Izy to offer a journey at a low price, but one which is still faster, safer, more sustainable and more comfortable than by car.

Railway Gazette, 2016.

The German case – Network effect and low-asset strategy

In March 2018, FlixMobility launched its brand FlixTrain, servicing a route from Cologne to Hamburg with an aggressive starting price of 9.99 € for the 400+ km ticket. For the first time ever, the DB (99 percent market share on long-haul routes in Germany) is facing competition. While there have been various operators trying to service routes throughout the years, none have managed to attract the customer threshold or comfortably position themselves in the asset-heavy industry. FlixTrain will prove to be a different player, as it can incorporate train routes into an existing network of bus routes, and has powerful financial investors and an established brand. After the launch, the DB responded by expanding its own array of low-cost tickets and including free add-ons, such as public transport city tickets, with existing offers.

In March 2018, FlixMobility launched its brand FlixTrain, servicing a route from Cologne to Hamburg with an aggressive starting price of 9.99 € for the 400+ km ticket. For the first time ever, the DB (99 percent market share on long-haul routes in Germany) is facing competition. While there have been various operators trying to service routes throughout the years, none have managed to attract the customer threshold or comfortably position themselves in the asset-heavy industry. FlixTrain will prove to be a different player, as it can incorporate train routes into an existing network of bus routes, and has powerful financial investors and an established brand. After the launch, the DB responded by expanding its own array of low-cost tickets and including free add-ons, such as public transport city tickets, with existing offers.

FlixTrain applies a low-asset strategy by investing in neither infrastructure nor hardware. It solely acts as an overarching sales arm, leaving operations to independent operators that profit from the successful brand name. The success on its three routes means the target of 500,000 passengers per annum is not out of reach. To achieve this goal, the routing offering is to be greatly expanded in 2019 (FlixTrain, 2018).

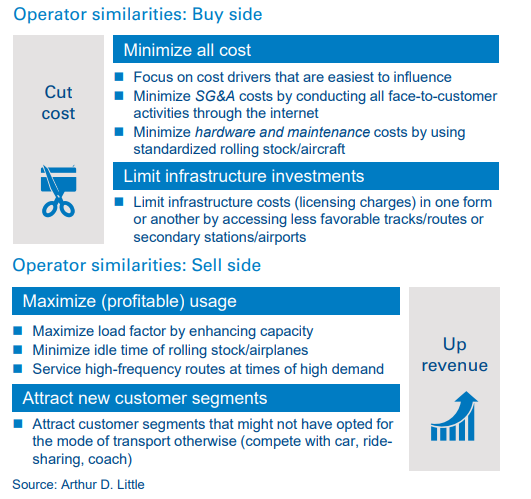

First learnings – Rail mirroring airlines

In the three use cases, operators mirror the airline LCC business model using the same means to cut costs and up revenue.

Unfortunately, no public record of profitability exists for the three use cases individually, as the brands are listed as part of the overall operations of the holding companies. However, the lowcost service is bound to be of use to the holdings in general. It is a way to broaden their customer reaches and link new customer segments to their brands.

Conclusion – Change is imminent, but complete disruption is unlikely

The first operators to enter this area have shown that the LCC business model can be of interest on long-haul, high-speed routes, and it is likely that we will see further spread throughout Europe. It is, however, highly unlikely that we will see major disruption in the market. Until the underlying cost structure of rail radically transforms, most changes will be seen on the marketing side and from the customer’s vantage point, rather than on the business side and from the operational set-up. For a railway operator to achieve the 25–50 percent cost advantage seen by airlines, at least, is unrealistic. Nonetheless, the low-cost segment in rail will undoubtedly bite into other segments. In contrast to airlines, for which 36 percent market share is made up of many individual LCCs (of which only some are owned by full-service carriers), in rail it will be existing monopolistic players cannibalizing their own market share.

Perchance the trend will further stimulate the debate on whether track fees should be lowered or the monopoly ownership of incumbents in both infrastructure and servicing of the infrastructure should be split up. A decrease in track fees and loosening of tight market regulation could lead to further technical democratization, and the resulting increase in competition from possible new entrants would benefit the customer. However, even if this is not the case, the rise in competitive pressures from mobility providers will certainly continue to facilitate the possibility of diversification of business models.