Defense entities are facing increasing complexity. While defense budgets are decreasing in real terms, the range of threats is widening. Managing the integration of technology and capabilities across land, sea, air, and space is ever more crucial. These challenges require an emphasis on core defense activities. Expanding private sector participation (PSP) in noncore defense services and assets is an option that improves focus, meets challenges, and frees up budgets for frontline activities. This Viewpoint explains how to identify the benefits and successfully initiate noncore PSP.

THE TIME IS RIGHT

Today, countries and their defense organizations need to be ready and able to respond effectively to growing geopolitical instability and ever-changing security threats. The nature of warfare has changed dramatically as well, with digitization and complexity impacting operations and forcing defense entities to adapt rapidly. From cyber warfare and asymmetric tactics to emerging technologies like artificial intelligence and unmanned systems, defense entities must master an elaborate set of new, interconnected challenges. These tasks are amplified by the general requirement of modern militaries to integrate forces across their different branches to ensure seamless operations and maximize overall effectiveness.

Many countries in Europe and Asia experienced defense budget growth in both 2021 and 2022, but defense budgets are under pressure in real terms in other regions. For example, the 2022 US defense budget shows a cut of approximately 6% in real terms, compared to its 2021 budget, according to IISS.

Because of greater complexity and budgetary pressure, defense entities need to channel their resources, senior staff time, and investments to where they deliver maximum impact. These changes are increasing the pressure on defense organizations to offload noncore services and assets to fully focus on core functions. Embracing PSP removes the need to manage such functions as noncritical utilities, hospitality, nonmilitary transport, retail, and supplies. The UK, for instance, introduced PSP to progressively remove assets and services that carry a significant cost burden but are not considered core capabilities (e.g., healthcare, training and education, and nonmilitary IT).

PSP benefits

Defense PSP creates three important benefits:

-

Financial. Embracing more efficient private operations delivers significant cost savings, while shifting the burden of capital investment to the private sector and enabling increased utilization of assets to generate new revenues. In the 1990s, the UK generated savings of approximately US $700 million by involving the private sector in almost 200 noncombat defense activities (see sidebar “The UK’s long defense PSP journey”). During the same decade, the US Military Housing Privatization Initiative secured around $30 billion of private investment to renovate housing units in poor condition and resolve accommodation shortages.

-

Qualitative. PSP and transferring activities to specialist providers improve the quality, availability, and timely delivery of assets and services, while supporting innovation and modernization. This enhances satisfaction with services, reduces complaints, and boosts the morale of personnel and their families. The US Department of Defense (DoD) demonstrated the benefits by choosing to privatize a large hotel estate (76 facilities with 11,600 total rooms) through open tendering. As a result, the new private operators dramatically improved quality of services provided without jeopardizing affordability for military personnel, veterans, and their families.

-

Administrative. PSP reduces the administrative burden on defense entities, allowing staff to concentrate on their core mandate. In the UK, the privatization of nonmilitary training facilities during the 2000s removed significant management, operational, and maintenance activities from the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD). Beyond cost savings, this considerably reduced administrative requirements in multiple departments, including equipment and support, HR, and logistics.

ENSURING SUCCESSFUL DEFENSE PSP

PSP efforts in defense organizations typically begin either as a centralized initiative aligned with national programs or on an ad hoc basis due to budgetary constraints or impending high capital investment activities (e.g., housing renovations). Regardless of what drives PSP, success requires a structured journey that includes three elements: (1) vision and objective, (2) strategy and plan, and (3) operating model.

1. Vision & objectives

The vision and objectives for a noncore defense PSP program should be based on the defense entity’s overall vision and strategy, local and international benchmarks, relevant laws, and stakeholder interviews. Setting a vision and objectives at the beginning of this journey and then amending them over the course of the program can guide PSP over the long term. In India, for example, the government’s defense PSP vision of self-reliance and empowering local businesses resonates with its wider objectives of increasing PSP and boosting the use of locally produced goods and services.

2. Strategy & plan

After establishing clear objectives, defense entities should create a robust PSP strategy that converts into a comprehensive strategic plan. This plan should provide clear instructions on how to privatize assets and services and include guidelines for prioritization and measurable KPIs for each objective to monitor progress and outcomes.

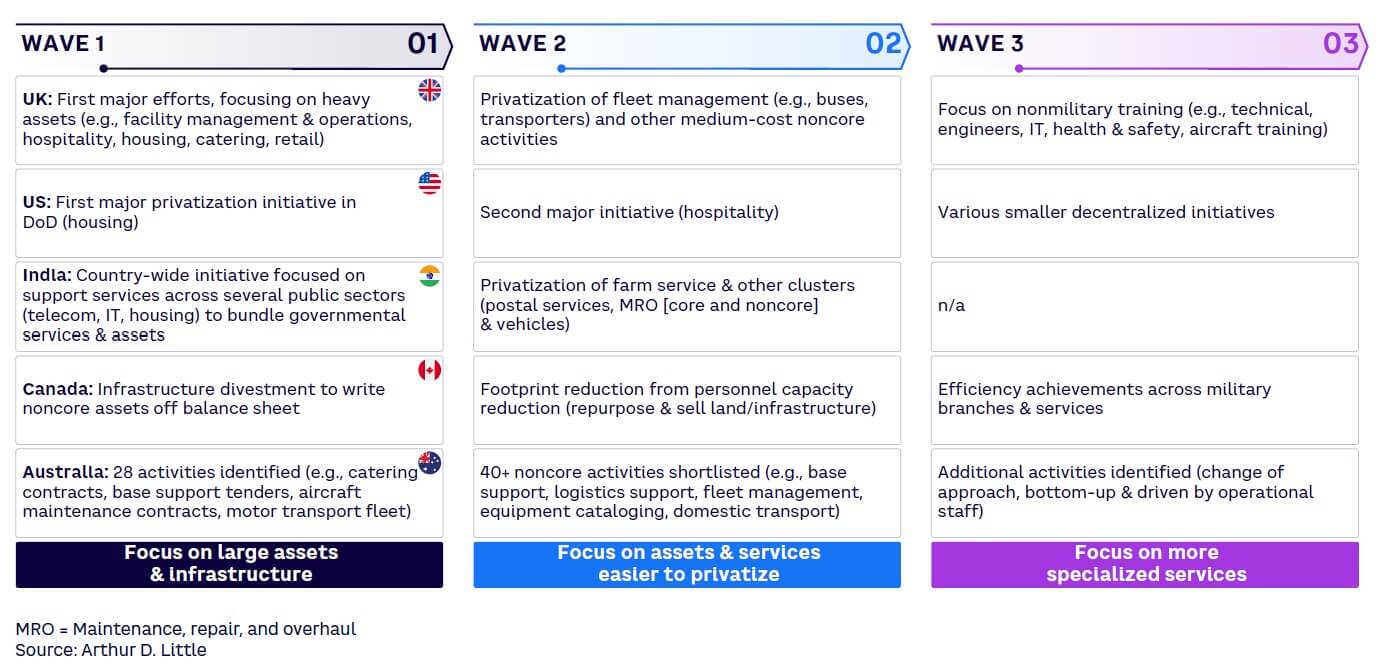

Experience shows that large-scale PSP programs tend to unfold in distinct waves, each corresponding to a different phase of the country’s strategic plan (see Figure 1):

-

Wave 1 — quick wins and big-ticket items. In the UK, for example, the first wave of PSP centered on heavy assets like facility management and operations, including hospitality, housing, catering, and retail.

-

Wave 2 — emphasis on specifics. Here, the focus shifts to assets and services that require a more detailed approach to transferring operations and developing contracts with a private party. These remain relatively easy to privatize, as there are extensive global experiences and best practices to follow. In the US, the move toward hospitality privatization is an example of one activity that may occur during this wave.

-

Wave 3 — final steps. If implemented, the third wave typically targets specialized services with complicated operations and a close affinity to core military services (e.g., training or IT). In the UK, the attention during this phase was on nonmilitary training, covering the technical, engineering, IT, health and safety, and aircraft segments.

3. Operating model

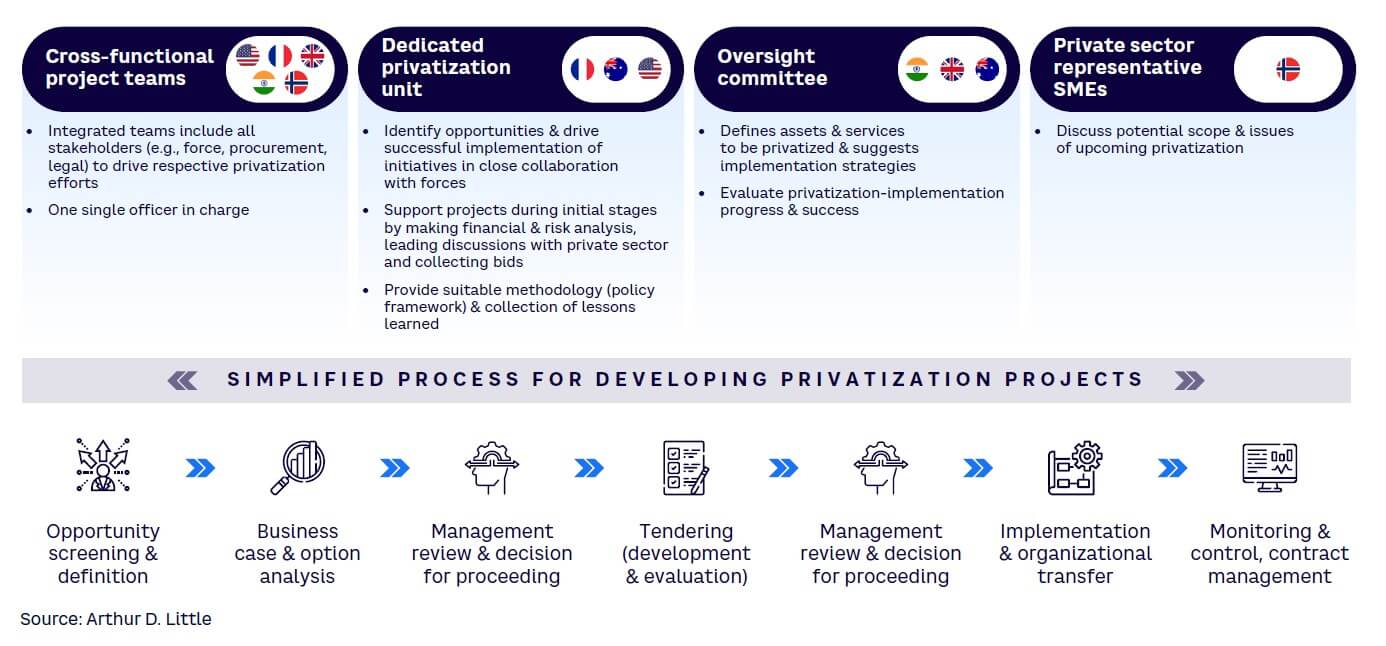

A successful PSP operating model needs to clearly outline overall organization for the work in addition to the mandate and model of the specific unit (see Figure 2). The optimal choice relies heavily on the scale of PSP and the degree of need for cross-functional coordination and efficiency.

Cross-functional project teams provide a good starting point in the early stages of PSP. These integrated teams bring together stakeholders from various functions, such as procurement, legal, finance, and planning, to drive respective PSP efforts. However, while this approach is initially suitable for the program, it might become overly complex as PSP scales up.

Instead, dedicated PSP units are a proven choice for larger-scale programs, as witnessed in the US, UK, France, and Australia. These units identify opportunities and drive the successful implementation of initiatives, collaborating closely with asset and service owners. They assist PSP projects to get them off the ground, providing financial and risk analyses, leading discussions with the private sector, and collecting bids. In addition, they may provide a policy framework and gather lessons learned for future efforts. In some cases, there is the establishment of an overseeing committee, as seen in the UK, Australia, and India. These define the assets and services for privatization, suggest implementation strategies, and evaluate the progress and success of PSP implementations.

Defining the mandate, positioning, organizational structure, and primary roles of the specific unit driving PSP is crucial. Successful countries, including the UK, France, and Australia, have opted for an “orchestrator” model, where the unit leads projects and acts as the main facilitator of public-private partnership efforts within the organization. Consisting of a mix of functional experts and project teams, it has high-level responsibility for projects and possesses significant decision-making power.

The unit’s positioning within the defense hierarchy is decisive. It should be high enough to exert the political influence needed to trigger and drive significant changes and be able to collaborate with key stakeholders, such as asset owners, planning, finance, and other relevant support departments, including HR, procurement, and legal. In both the UK and France, PSP units are two to three levels below the relevant minister to ensure adequate power and are on the same level as procurement and finance departments, enabling effective collaboration.

IMPACT & READINESS: PRIORITIZING PSP

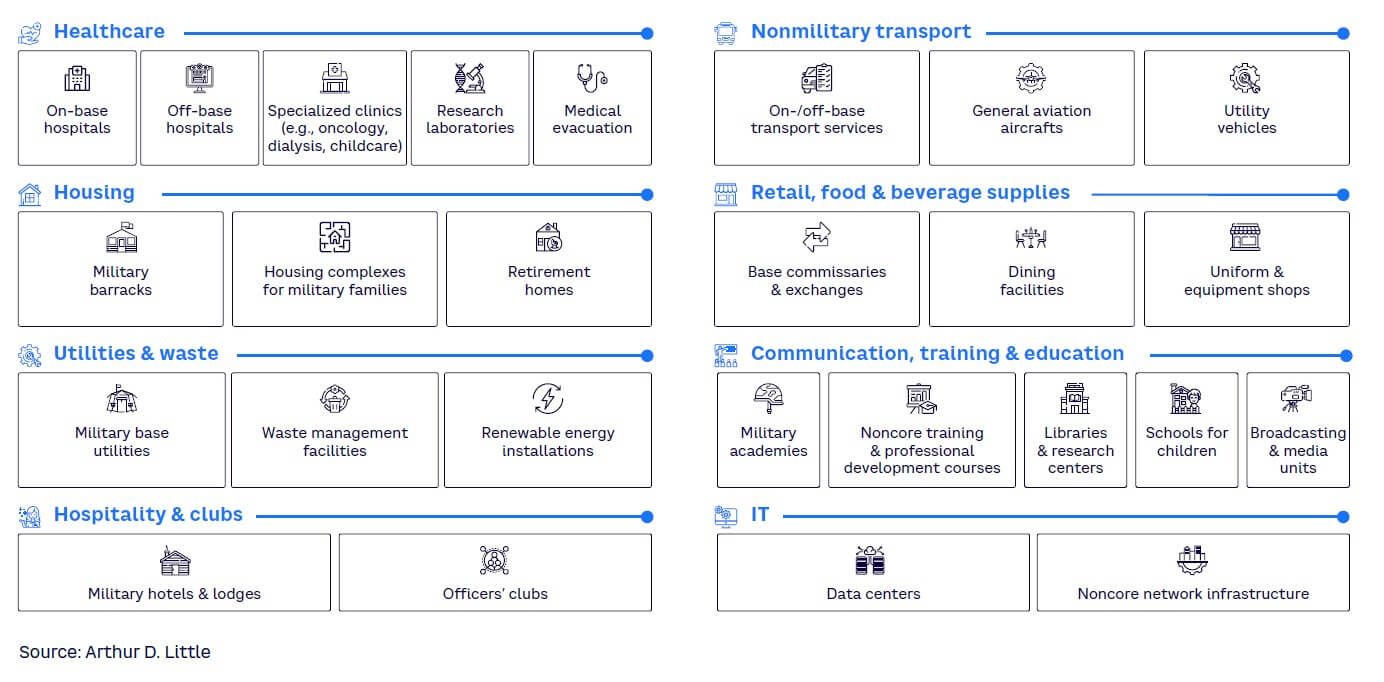

The range of services and assets provided by defense entities is potentially vast and needs effective prioritization setting when creating a convincing PSP strategy. Organizational functions must combine with everything involved in supplying, housing, feeding, and meeting the living requirements of their personnel and their families. A large number of these activities are noncore and fall under eight main categories:

-

Healthcare

-

Housing

-

Utilities and waste

-

Hospitality and clubs

-

Nonmilitary transport

-

Retail, food, and beverage supplies

-

Communication, training, and education

-

Information technology (IT)

The sheer scope of these assets and services means that choosing what to privatize and when requires careful evaluation and prioritization to maximize PSP benefits. While every country’s needs will differ, the following framework, based on the PSP journeys of defense entities around the world, lays out an approach that can be adapted to individual requirements:

-

Create an asset & service repository. First, understand and map all noncore assets and services owned by the defense entity and create a database that can be used to plan future PSP opportunities. These assets and services can be clustered based on category (e.g., healthcare, housing) or by the organization responsible. Figure 3 shows a sample database.

-

Identify critical assets and services. Certain assets and services are strategically important and cannot be considered for offloading. They may represent critical infrastructure (e.g., water desalination plants in hot countries or vital power-generation facilities close to military bases), contain confidential information (e.g., clothing and food supplies near military bases may reveal information about troop levels), or have other special characteristics (e.g., nonmilitary planes used by high-ranking individuals and state leaders).

-

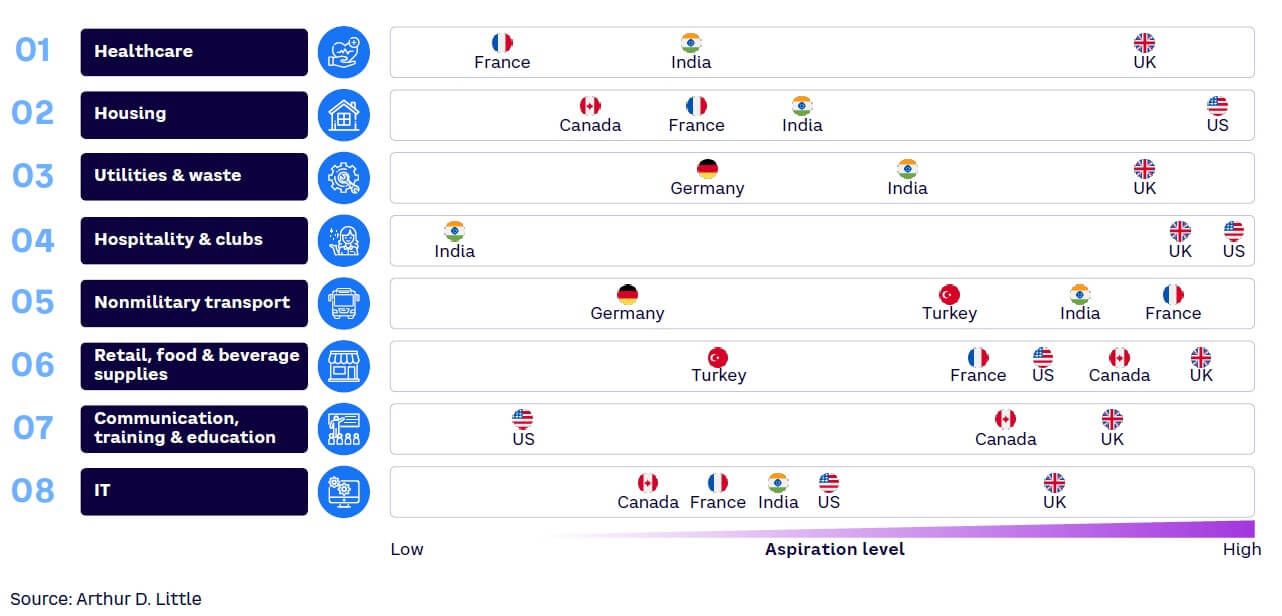

Define aspiration levels for each cluster. The level of PSP ambition will vary between countries and clusters of assets and services. Experience shows that countries are generally more ambitious about privatizing complex, high-CAPEX areas not connected to their core processes, such as off-base healthcare and housing. However, governments tend to be more cautious about assets and services that they rely on operationally like IT. Figure 4 shows the aspiration levels of different countries across clusters.

-

Identify all PSP opportunities. Knowledge gained during the previous steps will allow defense entities to create a long list of areas for privatization. Common low-hanging fruit includes the construction or renovation of housing; large, uncritical infrastructure (e.g., district cooling); or wastewater facilities and nonmilitary vehicles (e.g., buses, car fleets).

-

Evaluate the impact and readiness of opportunities. Set success criteria for PSP projects. For example, impact criteria might include quantitative, qualitative, and administrative benefits. Readiness criteria would focus on the availability and experience of private partners, international and local success stories, and any regulatory barriers. Evaluate project simplicity (e.g., number of stakeholders involved, degree of asset centralization, and estimated project duration) and internal readiness, including data availability, human capabilities, and previous experience.

-

Select focus opportunities. At the final stage of planning, build a short list of opportunities to ensure PSP efforts are well defined and effective. These are likely to include quick wins as well as other large, centralized but noncore assets, such as hotels, uncritical power generation, and large retail facilities, since operation of these and potentially their ownership will be transferred to a PSP depending on the chosen model.

Examples of success stories in specific clusters include:

-

Healthcare in Australia. The majority of medical and dental services were transferred to private entities. This approach led to ASPEN Medical being contracted for field operations and most on- and off-base health services. Pathology, imaging, and radiology services were transferred to Medibank.

-

Utilities in the US. The DoD successfully privatized a quarter of utility systems on military installations, including electricity, water, natural gas, and wastewater. Private companies are now in charge of upgrading, constructing, maintaining, and operating the infrastructure, with plans to privatize an additional quarter of systems in the near future.

-

Retail in Canada. Retail and food/beverage outlets were privatized through Design-Build-Finance-Operate (DBFO) models under the management of CANEX, the government-owned military store. A profit-sharing agreement was established between CANEX and the Ministry of National Defence, yielding significant financial and operational benefits for both entities.

The overall priorities settle on opportunities that yield high CAPEX or OPEX savings, support from key stakeholders across the entity, and the delivery of substantial improvements in quality for employees, soldiers, and their families.

Conclusion

MANAGE COMPLEXITY, CONNECT WITH PRIVATE SECTOR, SEE RESULTS

In a time of escalating pressures on defense entities, privatizing noncore assets and services has proved to deliver financial benefits, facilitate major investments, and enhance quality. As defense management becomes more complex, organizations should increase PSP efforts by initiating the following steps:

-

Set a proper PSP vision and objectives aligned with overall defense and/or national strategy, which establishes and covers benefits and ambition levels.

-

Create a robust PSP strategy to translate into a comprehensive strategic plan. Clear prioritization of the noncore assets and services intended for PSP is the desired outcome.

-

Design a PSP operating model that involves key internal and external stakeholders and effectively puts the right structure, authority, and capabilities in place to govern and steer programs.