ChatGPT arrived through lightning-speed adoption. Indeed, OpenAI confirmed that ChatGPT users surpassed 1 million just five days after its launch, making it the fastest-adopted app in history. And although not yet confirmed by OpenAI, we estimate that number grew further to somewhere between 100 and 300 million users by the end of January.

Why such a meteoric adoption? It wasn’t new technology, after all; in fact, the underlying technological brick, LLM (large language model), has been accessible via an API for two years. But if not the technology, what led to such a frenzy? It comes down to anthropomorphizing. In this Viewpoint, we explore the benefits and risks of anthropomorphizing an AI.

LET’S TALK ABOUT ANTHROPOMORPHIZING

Monday, 27 February 2023, Arthur D. Little, Paris. I grab the long vertical handle of the right door. As always, I pull. The door does not open. So I immediately grab the left handle and pull with the same result. Fooled again! You have to push to get inside! I enter the meeting room where I find my guest, Yann Lechelle, waiting for me, and say to him, “Another poorly thought-out man-machine interface.”

Yann replies, “Yes, it’s a problem of affordance.” Unfamiliar with the term, Yann explains that affordance (or potentiality) is the property of an object that suggests its use to a user. A metal plate on a door invites pushing, while a vertical handle invites pulling. The theme of our conversation quickly becomes apparent as we talk about artificial intelligence (AI), affordance, and anthropomorphizing. This Viewpoint is inspired largely by that discussion.

Yann and I have known each other for five years. He’s an amazing guy — a digital entrepreneur who led and significantly developed Scaleway, a leading cloud player in France. Prior to that, he participated in the creation, growth, or sale of several start-ups. He was the COO of the start-up Snips, specializing in AI applied to voice assistants, until its acquisition by Sonos at the end of 2019. So it just so happens that the interface with an AI is among his special areas of expertise.

I have thought a lot about why the LLM GPT-3.5 had been made public in the form of the chatbot, ChatGPT. Indeed, the chatbot invites the user to believe that it was endowed with advanced cognitive abilities and that we can ask it questions, get answers, and assume that these answers will be correct. As a result, we can also presume that a tool like ChatGPT will replace traditional search engines like Google.

However, it is clear that the answers ChatGPT provides often leave something to be desired, as we explored in the Viewpoint, “My kids have replaced me with ChatGPT.” The quality is not always there. The answers it shares are sometimes vague or even false. But these results are to be expected: ChatGPT is not designed to answer questions. It is, in fact, even less designed to give correct answers. ChatGPT is based on an LLM whose mission is “simply” to produce the most likely word as an output given a series of input words. Then to provide yet another word. And so on.

ChatGPT is a kind of autocomplete tool, similar to what our smartphones do when we type an SMS — except with a little more sophistication. The ability to answer questions is, in a way, a phenomenon emerging from the fact that the model has been trained on an exceptionally large corpus of documents and conversations. But the risk remains that the answer will often be off the mark. Still, the chatbot aims to anthropomorphize the underlying AI.

ANTHROPOMORPHIZING AIs TO REDUCE BARRIERS OF ADOPTION

So why anthropomorphize? Anthropomorphism is derived from the Ancient Greek ἄνθρωπος/ánthrōpos/ánthrōpos (“human being”) and μορφή/morphé (“form”) and originated in the mid-1700s. In literature, it is sometimes called “personification.” It refers to the process by which humans attribute human traits to nonhuman objects, such as animals, plants, and machines.

The anthropomorphizing of AI is a topic that arouses a lot of interest in academic and industrial circles, as well as in popular culture. In the case of AI, this means that humans attribute human characteristics such as speech, thought, emotion, and consciousness to these machines.

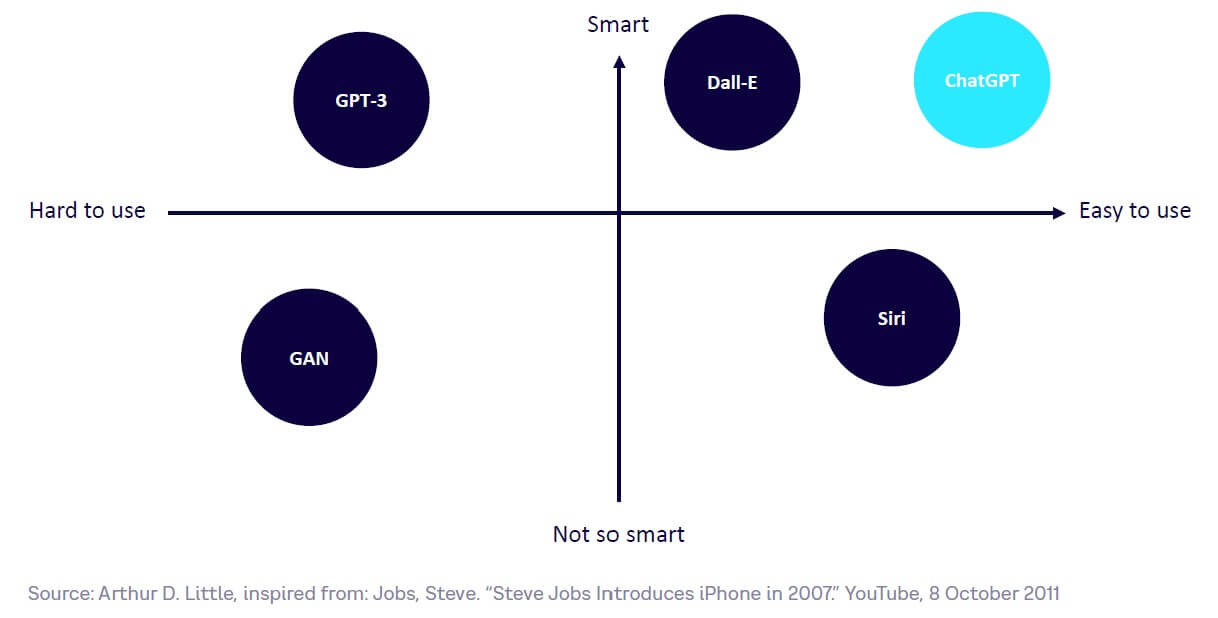

Anthropomorphizing an AI during its design has a major advantage: it reduces the barriers to the use and adoption of the technology. This is the notion of affordance that Yann pointed out to me: everyone knows how to hold a conversation; so everyone will know how to use ChatGPT and thus build sophisticated queries, simply interacting with the chatbot. As Figure 1 illustrates, anthropomorphizing is largely responsible for the rapid adoption of ChatGPT.

Strangely, even if the conversational ability may prove in the future to be no more than anecdotal, it has been striking, even staggering, for most of us. And why haven’t other generative AIs — such as Dall-E 2 or MidJourney for image generation, also released in 2022 — been adopted as quickly? The reason is that everyone knows how to hold a conversation, but not everyone is an artist, a photographer, or a graphic designer.

Similarly, mainstream end users have not used GPT-3, even though it is as “smart” as ChatGPT, simply because it is much harder to use. And even well-known vocal assistants like Siri, Alexa, and OK Google have not yet become mainstream despite the fact that they are easy to use because they are not “smart” enough. Even Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella told the Financial Times, “They were all dumb as a rock.”

ANTHROPOMORPHIZING AIs TOWARD MASSIVE ADOPTION BY DEVELOPERS & ENTREPRENEURS

All waves of innovation and industrial revolutions tend to follow a similar pattern: scientific discoveries are made, and on that basis, technological bricks are built. Initially adopted by a minority, major breakthroughs take place at the business and societal level when they are adopted by a majority. As we have seen, anthropomorphizing facilitates adoption by end users, but it also facilitates adoption by developers and entrepreneurs — in fact, anthropomorphization is key for rapid growth in order to unleash the great Schumpeterian “gale of creative destruction” that will transform the status quo.

In this era of widespread adoption, innovation is synonymous with combination: finding ways to creatively combine technological bricks to invent new uses or new business models. Innovation also means testing many things, the majority of which will be doomed to failure.

APIs and the current low-code/no-code wave are just some of the technological bricks driving the adoption of AI. Companies such as Hugging Face, a US start-up founded in 2016 and already valued at US $2 billion, aims to democratize AI by providing models already trained via APIs or visual development interfaces. The years 2022 and 2023 are going to be pivotal in the history of AI, because for the first time very sophisticated tools have become easily available for developers and entrepreneurs.

ANTHROPOMORPHIZING AI IS A RISKY BET

So we can see that anthropomorphizing AI accelerates its adoption — both by users and by developers and entrepreneurs — and rushes us into the great Schumpeterian creative/destructive growth phase. However, anthropomorphizing has some limitations and does not come without risk.

First of all, as mentioned earlier, anthropomorphic AI may lead to disappointment. The majority of players offering voice assistants (Google, Apple, and Amazon) have opted for human voices — and therefore anthropomorphic AIs. This gives the user the impression that Alexa, Siri, or OK Google have advanced cognitive abilities, which is obviously not the case, and often leads to feelings of frustration and disappointment with use. This pitfall is well known and sometimes called the “uncanny valley,” referring to a theory formulated in 1970 by the Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori. According to the theory, the more a robot resembles a human being, the more its imperfections become apparent and evoke a feeling of strangeness, discomfort, or cognitive dissonance. In this case, the robot is judged not as a robot that manages to pass itself off as human, but rather as a human that fails to act normally. The same goes for AI.

In addition, anthropomorphism that is too exaggerated can be misleading. In particular, it can lead users to believe that the AI they are interacting with is conscious or sensitive. In 2022, Google engineer Blake Lemoine got caught up in his own game and eventually convinced himself that LaMDA, Google’s chatbot, had become sentient. The conversation between Lemoine and the AI is indeed striking and illustrates the underlying risks.[1]

Another risk of anthropomorphizing is a direct corollary of speed of adoption. The first Industrial Revolution lasted at least a century after the invention of the steam engine. The system (companies, education, etc.) had time to adapt so that the revolution was ultimately synonymous with human progress. The current revolution in AI — and especially generative AI — is steeply exponential. Especially those professions that produce and work with content (text, image, speech, video, etc.) will be massively impacted. Some jobs, including white collar jobs hitherto untouched by automation, may disappear, almost literally overnight. This destruction may not be classifiable as Schumpeterian creative destruction because the system may not have enough time to adapt.

Finally, the last risk of anthropomorphizing and rapid adoption of AI is the lock-in risk. Some of the platforms mentioned above are becoming essential. Today, a start-up needing AI capabilities at scale would be able to use the infrastructure of these platforms very easily almost free of charge, and thus become heavily dependent on it. In addition to the risks to society of concentrating huge power in the hands of a few digital giants, today’s unstable geopolitical environment, in which issues of national sovereignty appear to be increasingly important, makes lock-in to, say, a US or Chinese platform, even more problematic.

Conclusion

Some issues to ponder

We recently conducted a survey on LinkedIn asking whether AI should be “anthropomorphized because it reduces barriers to adoption, even if it raises questions and presents risks.” Almost 70% of the respondents disagreed.

Anthropomorphistic AI is accelerating rapidly to maximize adoption both by end users and by developers and entrepreneurs. But we might want to reflect on whether the scale and speed of this development is really in the best interests of us all — individuals, businesses, and society at large. For example:

-

Could AI suffer from Mori’s “uncanny valley” of emotional response from users, even leading to a major trough or backlash?

-

How big is the risk that the speed of creative destruction through anthropomorphic AI will be so fast that it destroys more than it creates?

-

How can we encourage and regulate the right market conditions to avoid an AI stranglehold by a few giant corporations?

-

What sorts of strategies should companies take in relation to exponential AI adoption?

Notes

[1] Lemoine, Blake. “Is LaMDA Sentient? — An Interview.” Medium, 11 June 2022.