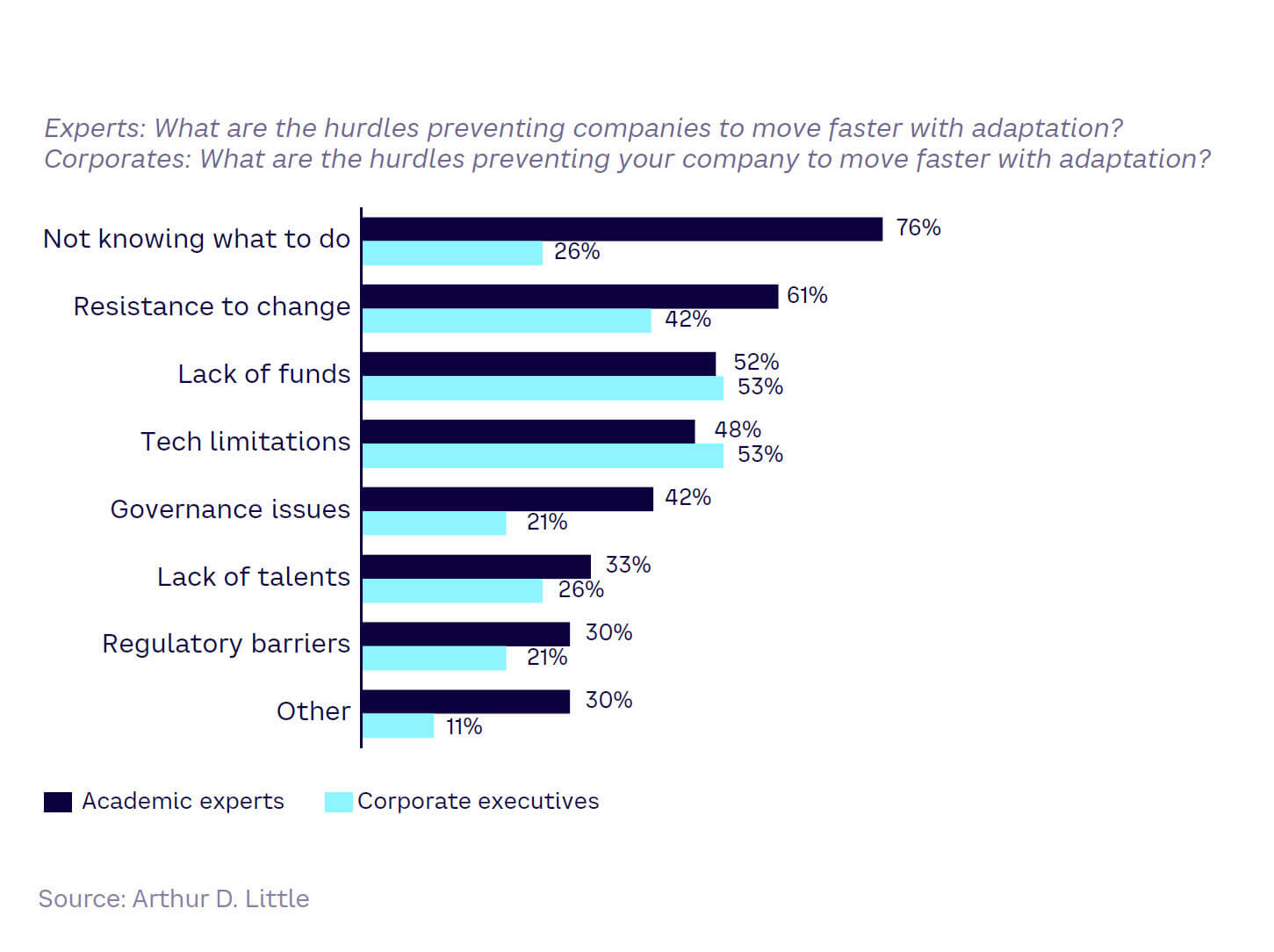

Despite the urgency to adapt, and the general availability of mature technology, companies face considerable hurdles in implementing adaptation initiatives.

Overall, a lack of knowledge among corporate executives on the best course of action is perceived as the main hurdle to business adaptation (see Figure 13). The difference in knowledge between experts and executives is striking. Executives also emphasize limitations with current technology (53%) and lack of financial resources (53%) as challenges, while academic experts emphasize cultural resistance to change (61%). Comparing the academic and business viewpoints, companies are focused more on external hurdles to adaptation (e.g., technology), whereas experts see internal, human factors like lack of knowledge, culture, and governance as obstacles. Experts also highlight the lack of financial rewards and regulations required to drive technological advances as key hurdles for companies not adapting.

“At Michelin, we developed our own warming trajectory combining various development strategies adopted by public and private actors, resulting in a GHG emissions scenario, which we converted into warming based on IPCC models.” — Gael Queinnec, Expert in Corporate Foresight and Development (former Foresight Director at Michelin)

“In my industry, which is strictly B2B, consumer behavior shift won’t have a great impact unless my customers adjust to it.”— Chief Technology Officer, Advanced Materials Manufacturer

Addressing implementation hurdles

To address the implementation hurdles highlighted in our research, businesses need to address four key questions outlined below.

How to predict?

Build assumptions

Decision makers should begin the adaptation process by creating their own global warming trajectory assumptions. The IPCC offers several RCP trajectories — companies should choose which they wish to adopt given their circumstances, monitoring their choice regularly to ensure it remains relevant.

From this, they should select the shaping factors most relevant for themselves and their market. This could depend on factors such as their place in the value chain (e.g., B2C players are directly affected by shifts in consumer behavior), market positioning (players in a stronger market position are more likely to lead on adaptation, while others follow), the location of their industrial footprint and of the markets they serve, and the specific drivers of their industry, including the role of regulation and the structure of R&D.

They then need to identify the most relevant projections from the five outlined earlier in this Report. Some specific combinations of factors may not be consistent or relevant for all companies; conversely, the tension between some factors may lay at the core of their adaptation and broader strategy.

“A scenario with adaptation funding but no regulation is not realistic in my industry.” — Isabelle Esser, Chief Research & Innovation, Quality & Food Safety Officer, Danone

Assess risks

Once these working hypotheses are in place, organizations should carry out a site-by-site assessment to understand potential risks, both acute and chronic. Analytical tools, such as GIS, can help provide a comprehensive picture of potential risks, along with growing volumes of relevant, freely available data. Understanding this data and using it for insightful decision-making requires analytics capabilities, which should ideally be built in-house or outsourced to a third party (e.g., an insurer). The most critical operations may benefit from being digitally twinned to anticipate the occurrence and severity of climate impacts. A granular approach is possible here, where only the most critical machines or workshops are monitored thoroughly. As indirect risks are harder to identify and model, they are best addressed by a separate stream that involves members of the supply chain function.

Launch pilot projects

Impact-quantification tools can first be deployed on a specific, wellbound, and local adaptation problem. For example, ADL worked with the executive committee of a railway operator to create a forwardlooking risk capability to better anticipate negative issues caused by severe climate events that led to fallen trees on its lines. Focused on a specific area, it ran an eight-week proof of concept to create an interactive map–based dashboard that brought together real-time meteorological and geographical data to model risk using AI and then provided risk scores over a 24-to-120-hour time horizon.

How to decide?

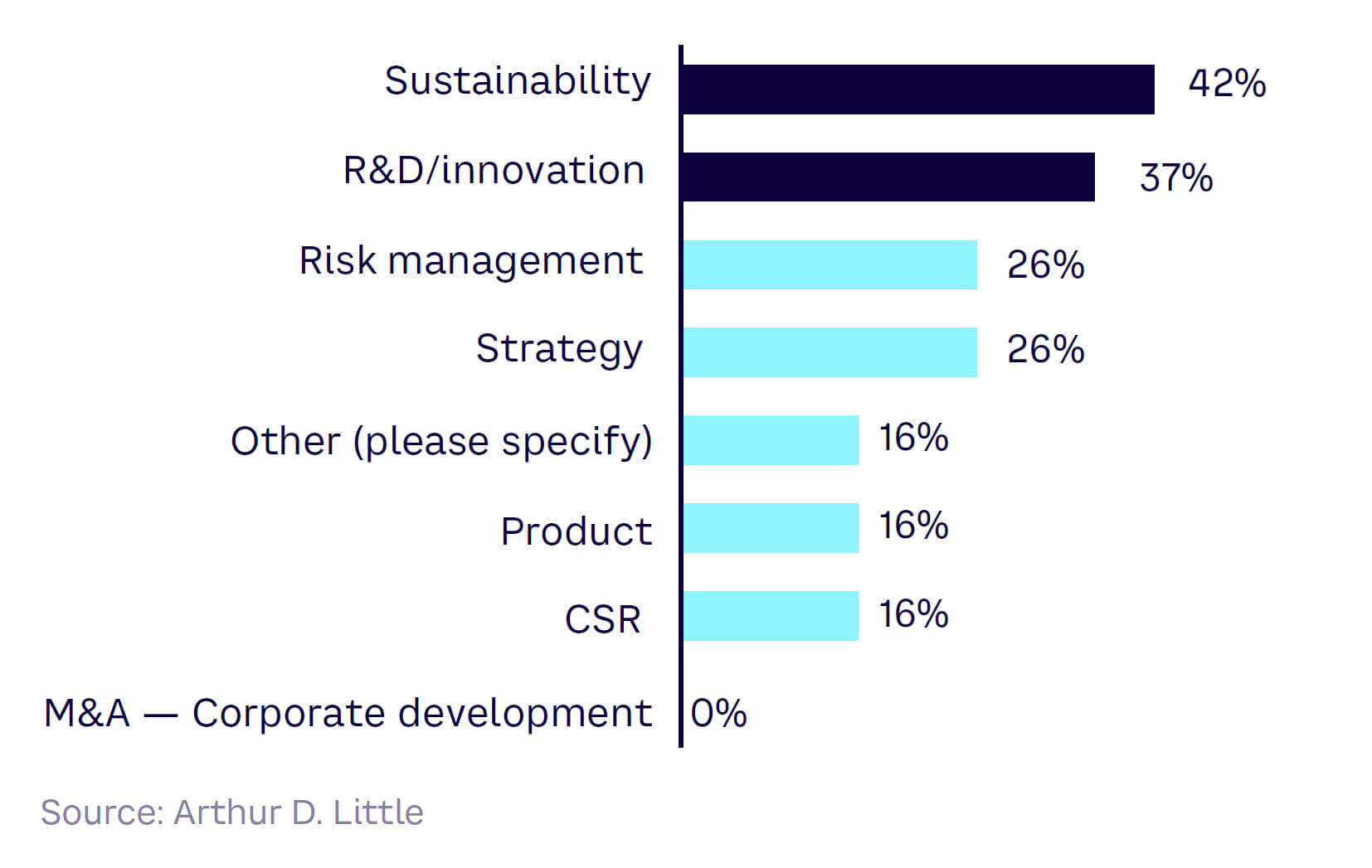

Currently, adaptation topics are handled by a range of functions across organizations, most commonly within sustainability, R&D, and risk teams, as shown in Figure 14. In the most adaptation-conscious companies (self-rated as the most mature), the CEO and R&D department are both involved. However, most often, parts of the adaptation agenda are owned by different functions, creating information loss, friction, and inefficiencies.

Create a dedicated team

To ensure clear focus and accountability, we recommend creating a dedicated adaptation task force, able to centralize:

- The culture of climate science, which evolves rapidly

- An understanding of strategic and operational impacts across all parts of the company

- Knowledge of available technologies

- Knowledge of private and public adaptation ecosystems

- The ability to own account experimentation with adaptation solutions

- Approaches to building resilience and seizing opportunities (new products, services, channels) from adaptation

We recommend adaptation be managed separately from mitigation as the impacts on the top line and the influence of regulation differ largely between both goals. However, we advise an overarching governance structure that covers both adaptation and mitigation efforts, as some investments, such as water-efficiency systems, serve both. The adaptation task force should propose criteria and tools to measure the effectiveness of its actions, over and above traditional risk management efficiency.

Understand & overcome challenges

There are three key challenges around adaptation decision-making, and all need to be understood and addressed:

- Adapting risk metrics. New metrics need to be considered as new types of risks emerge (e.g., production time lost to heat or faster asset degradation). Risk thresholds also must be reassessed and adjusted to position climate impacts as a core variable, while multi-speed timelines must be considered. For example, risk profiles for specific assets or operations may change gradually and then suddenly — a change from traditional linear risk profiles.

- Listening to the customer’s voice. Traditional methods of listening to customers to uncover their preferences may not apply in the adaptation context as it is outside the experience and immediate understanding of many individuals and businesses. To collect valid customer insights, it is better advised to analyze customer behaviors in response to events that foreshadow the new normal (e.g., shortages, epidemics, catastrophic storms); for example, by using NLP or neural network–augmented social listening tools.

- Thinking global. Climate-related risk will disproportionately affect some locations, leading some regional business units to bear the brunt of the adaptation cost and risk and become unproductive or unprofitable. This could bias corporate decision-making, leading to suboptimal choices (e.g., exiting lower-cost, vulnerable countries altogether). Global governance supported by investment vehicles in adaptation is therefore needed to correctly assess strategic options regarding the overall production footprint.

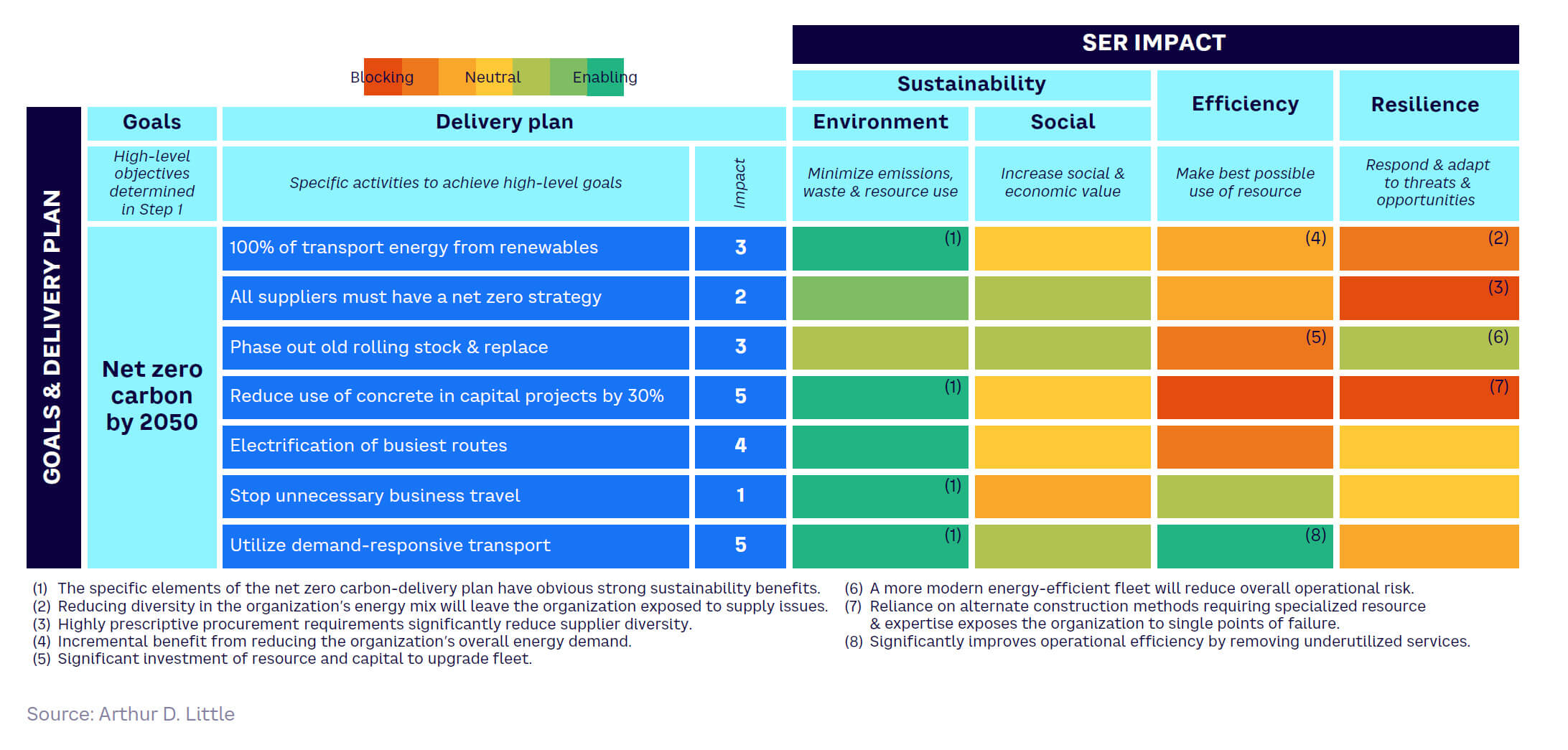

Assigning priorities

Decision makers may need to prioritize effort and investment between different adaptation goals. Using a heat map approach such as in the example shown in Figure 15 — which refers to sustainability, efficiency, and resilience (SER) — can often be useful in this respect.

How to finance?

Mobilizing funding for adaptation requires updating financial metrics. This includes pricing climate-risk vulnerabilities in terms of damage to assets, production loss, and possible reputational effects. Less intuitively, it may also involve the complex task of pricing positive externalities (productivity gains, employee retention) and potential market opportunities from adaptation (market share gains or new product-market fit). It also requires working with longer timelines (>15 years) than customary for most corporate decision-making.

Blended finance solutions, which combine concessional public funds with private capital, can be leveraged when corporate adaptation investments impact communities (e.g., via the financing of infrastructure, as is often the case in emerging markets). Blended finance may use instruments such as bonds and notes (privately placed securities or public issuances). The Climate Resilience and Adaptation Finance Technology Transfer Facility (CRAFT) is an example of a blended finance initiative, offering companies that invest in adaptation solutions grants for technical assistance (funded by concessional support). It may also rely on facilities like private equity funds or fund-of-funds structured with concessional capital.[23] However, to this day, adaptation-blended finance remains timid, mostly flourishing when hybridized with mitigation investments, and even then, mostly in the agricultural sector

How to build?

Once decision-making hurdles have been overcome and finance is in place, the building of solutions is best undertaken with local partners, under a clear IP regime and with ample time for experimentation. In practice, this will be a continuous and repeated process over many years.

Develop an ecosystem of local partners

Adaptation problems require local solutions, often best supplied by local providers with a deep understanding of local climate issues, who can operate on-site quickly and affordably. That means that developing local ecosystems of partners, beyond single opportunistic collaborations, is essential, requiring organizations to build the capability to identify and contract with partners locally.

Be savvy with IP

To ensure a well-functioning partner ecosystem to build innovative adaptation solutions, it is important to set clear ground rules for how IP will be managed. These should clarify rules for IP identification, ownership, usage, and documentation. Clarity on IP is also key for attracting finance and for supporting transfer and diffusion of adaptation technologies. Patent databases are useful sources for innovation scouting. Among the most comprehensive are WIPO’s PATENTSCOPE and the European Patent Office’s Espacenet.

Factor in experimentation times

Adaptation solutions often require longer experimentation times than other innovation solutions due to three factors:

- The longer-term nature of the process (e.g., it takes time to regenerate agricultural soils).

- The nature of climate risk (e.g., floods may not occur every year, and average temperature increases may be linear but can take time to cause impacts).

- Stakeholder acceptance (e.g., many adaptation solutions require time to generate acceptance and uptake such as communities required to change their agricultural practices).

Experimentation times should therefore be factored into adaptation investments, requiring even longer-term planning.