53 min read • Technology & innovation management

From good to great: Enhancing innovation performance through effective management processes

Results of the 9th Arthur D. Little Global Innovation Excellence Benchmark

Executive Summary

AVOIDING WASTE IN INNOVATION INVESTMENT

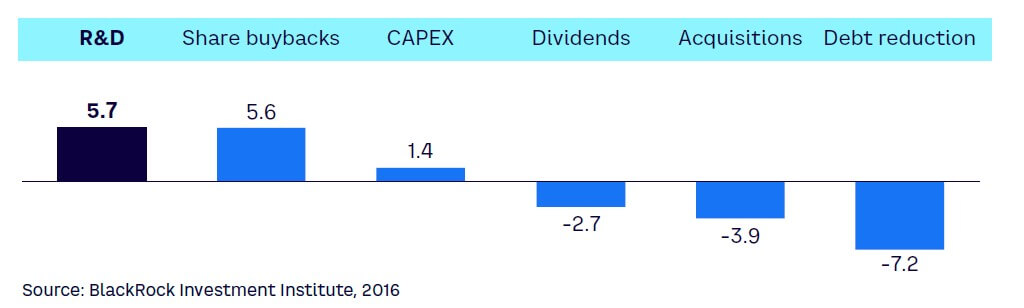

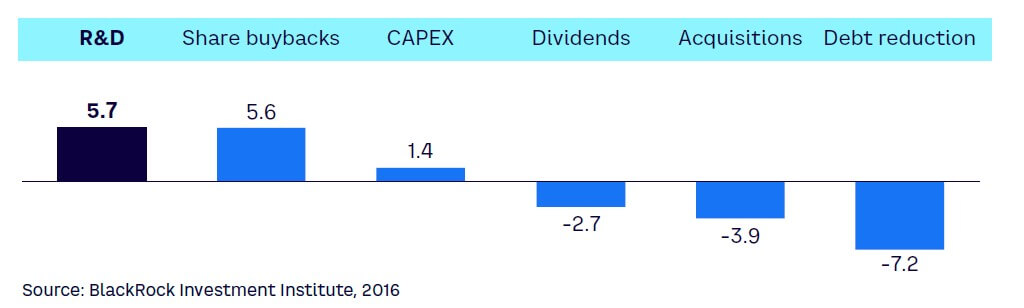

Innovation is essential for solving today’s global challenges and for the creation of differentiated new products and services that lead to profitability and growth. As an example, research carried out by Arthur D. Little (ADL) for the Association of Swedish Engineering Industries in 2023 found that investment in R&D generated a 7x return on innovation investments made by the Swedish state. Analysis comparing total shareholder returns of various types of capital usage has long indicated that over time and on average, R&D provides better shareholder returns than CAPEX, share buybacks, acquisitions, debt reduction, or dividends.[1]

Over the last 10 years, however, returns on and satisfaction with innovation have been in decline.

In fact, a lot of R&D investment is “wasted,” partly because it is in the nature of innovation to be uncertain and many ideas and projects turn out to be unrealizable. However, much waste is not necessary and is caused by weak innovation management processes. We continue to see:

-

A clear relationship between measures of innovation management and overall innovation success (measured in terms of new product or service sales contribution, EBIT margins, and time to breakeven). For most companies, there is clearly a significant payoff to improving innovation management.

-

Investment in R&D that is not globally correlated with innovation success. Unless your company is the top quartile in terms of innovation management, further investments in R&D and innovation do not appear to pay off.

We estimate that it is possible to achieve well in excess of 30% improvement in terms of innovation success for companies that score outside of the top quartile in innovation management.

While the innovation approaches of leading companies, from Apple to Tesla, are held up as role models, their practices may not be applicable to other, very different, organizations and industries. It can therefore be difficult to identify the most relevant best practices and understand what specific changes need to be implemented to help your own organization achieve innovation success. So where should you start?

Built on hard empirical evidence of what really works when it comes to managing innovation, ADL’s Global Innovation Excellence Benchmark (GIEB) highlights the innovation management practices that correlate most strongly with innovation success across different industries. Running for more than 25 years and nine editions, the GIEB allows companies to rank and profile themselves versus their peers on their innovation performance. The latest edition provides new insights about the drivers of innovation success and the link between innovation and growth.

The Report highlights key trends from ADL’s proprietary and proven Innovation Excellence Model as well as data from 2018 onward, which point to five specific focus areas to improve innovation management practice. These are the areas in which leading innovation organizations have excelled and which have been demonstrated to reduce investment inefficiency and improve returns:

-

Breakthrough innovation management practices. ADL analysis shows that those companies that proactively invest more in less certain innovation endeavors, including breakthrough innovation and building out new technologies in new markets, have higher overall innovation success. They generate greater revenues and margins from new products, services, and business models.

-

Business model innovation management practices. Business model innovation can drive sustained profitability for businesses of all sizes, delivering productivity and growth opportunities. It is an area that benefits from deploying the power of AI to reconfigure processes and value chain positioning. However, it is often overlooked; most organizations struggle with it. ADL’s experience shows that companies need to challenge themselves and understand their “nightmare competitors” to disrupt themselves. Implementing this means engaging with multiple stakeholders within and outside the business to tackle common barriers that hinder success.

-

Closing the gap between business units. ADL research shows that the typical gap in innovation management practices between different business units within the same company is sizable, contributing to lower overall performance and lost revenue and profit. The issue can be addressed by having the right innovation governance strategy, creating common forums and spaces for collaboration, and sharing innovation practices better across the organization.

-

Agile innovation management practices. Firms with a capability to execute innovation projects in an agile manner with the right tools tend to have overall higher innovation success. Processes must be in place to allow for multidisciplinary teams to be assembled, with iterative working and governance that do not act as a bottleneck. Properly adopted and tailored to the nature of the industry, companies can create a competitive advantage by identifying bigger ideas, developing them faster, and executing them better and more efficiently.

-

Leadership. The capabilities and behaviors of those leading innovation effort have a huge impact on its effectiveness. Innovation leadership is no different than any other form of business leadership; it requires a combination of strategic thinking, strong communication skills, problem-solving abilities, emotional intelligence, and integrity. But innovation has changed. To meet new needs, innovation leadership needs to now focus on five key capabilities: vision belief, meta knowledge, network skills, perspective originality, and a digital-first mindset.

Throughout the Report, we provide evidence on innovation management trends and share practical advice on good practices to address weaknesses.

The ADL GIEB is a continuous process, and we would be delighted to receive your contributions either to the survey or to further reporting. We hope that you find it informative and useful for your ongoing innovation management efforts.

1

STRENGTHEN MANAGEMENT PRACTICES FOR BETTER INNOVATION RESULTS

by Ben Thuriaux-Alemán, Dr. Habib Hussein, Dr. James Semple, Dr. Michael Kolk, Martin Glaumann, Rick Eagar, and Frederik Van Oene

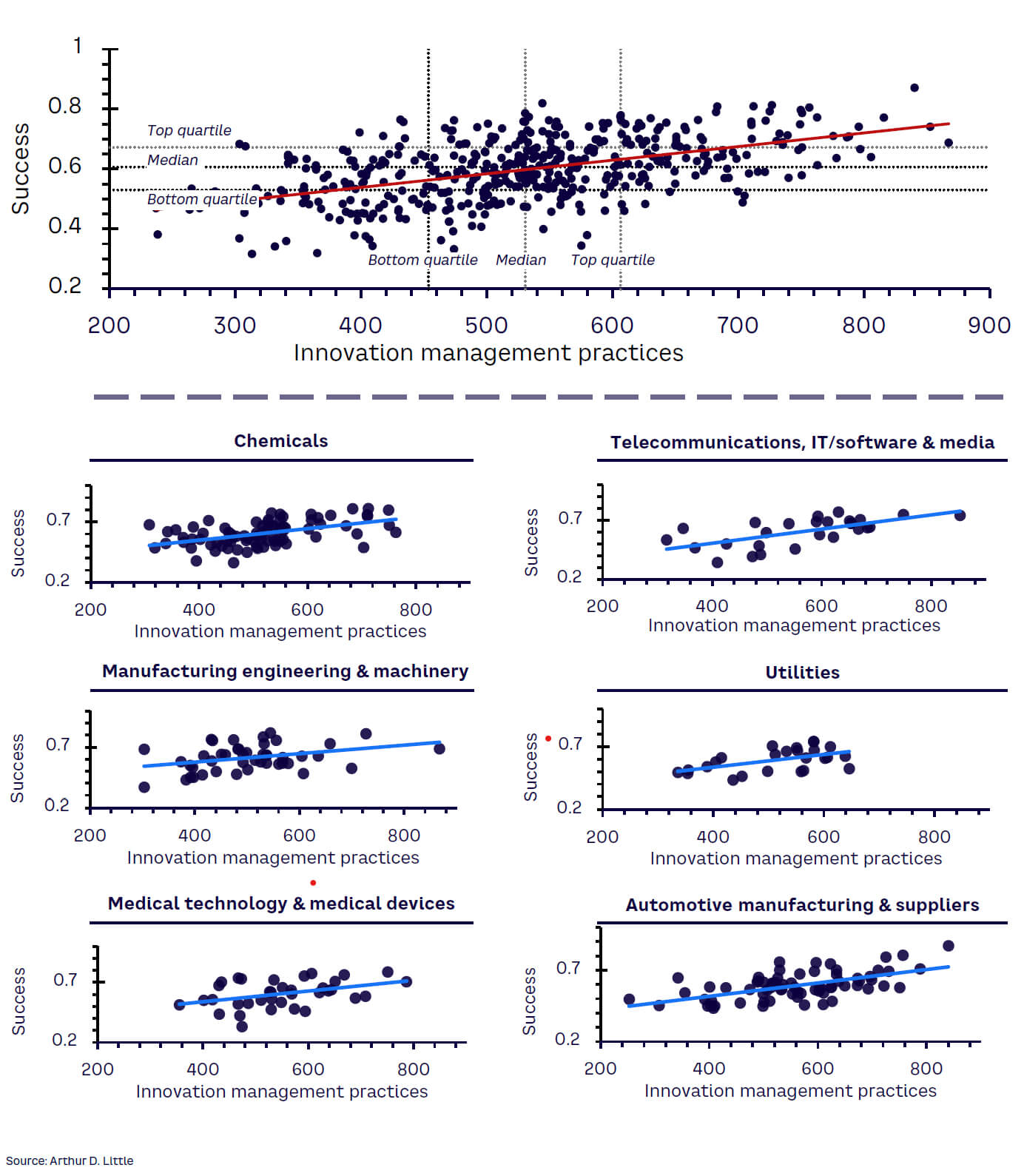

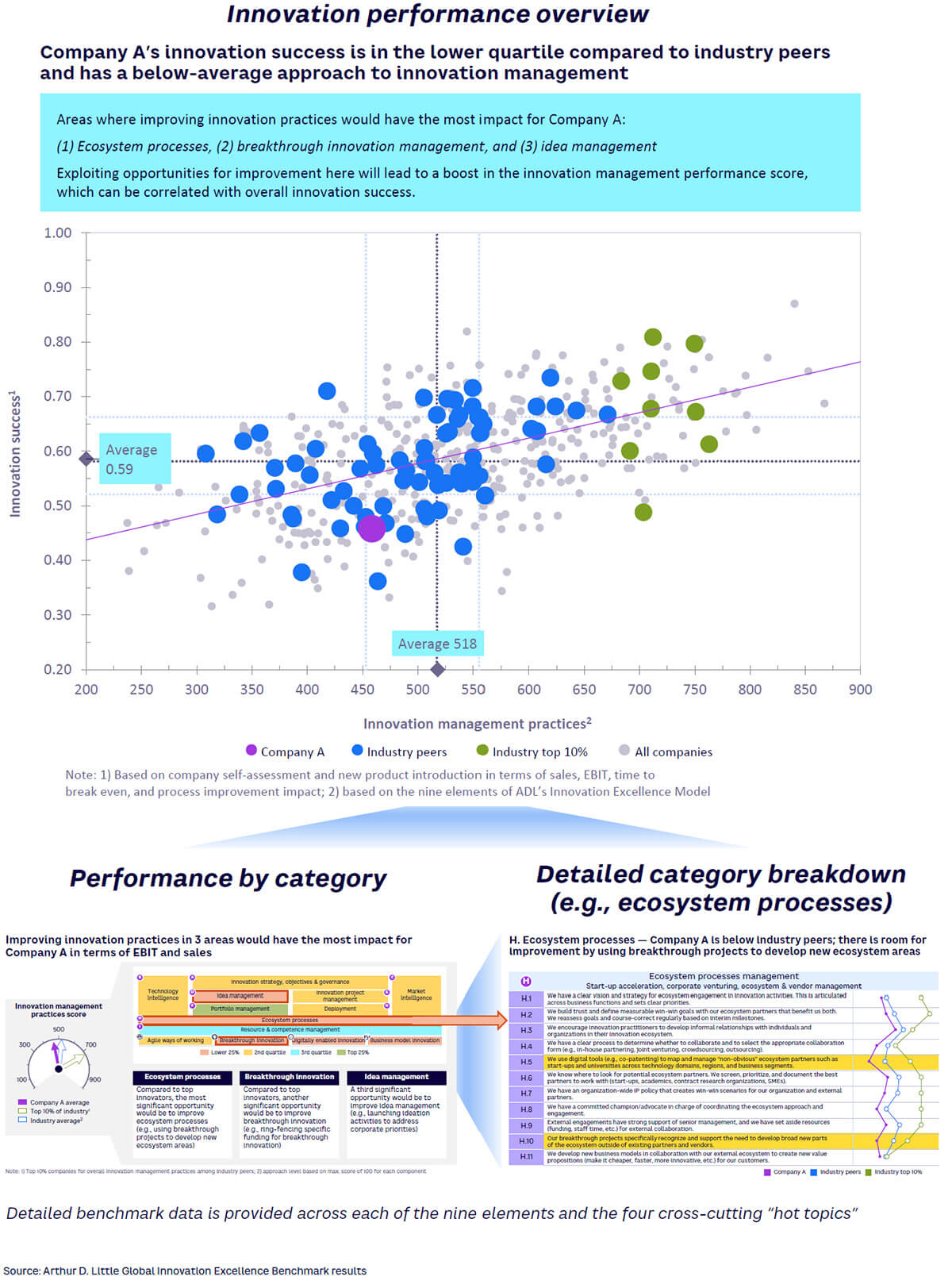

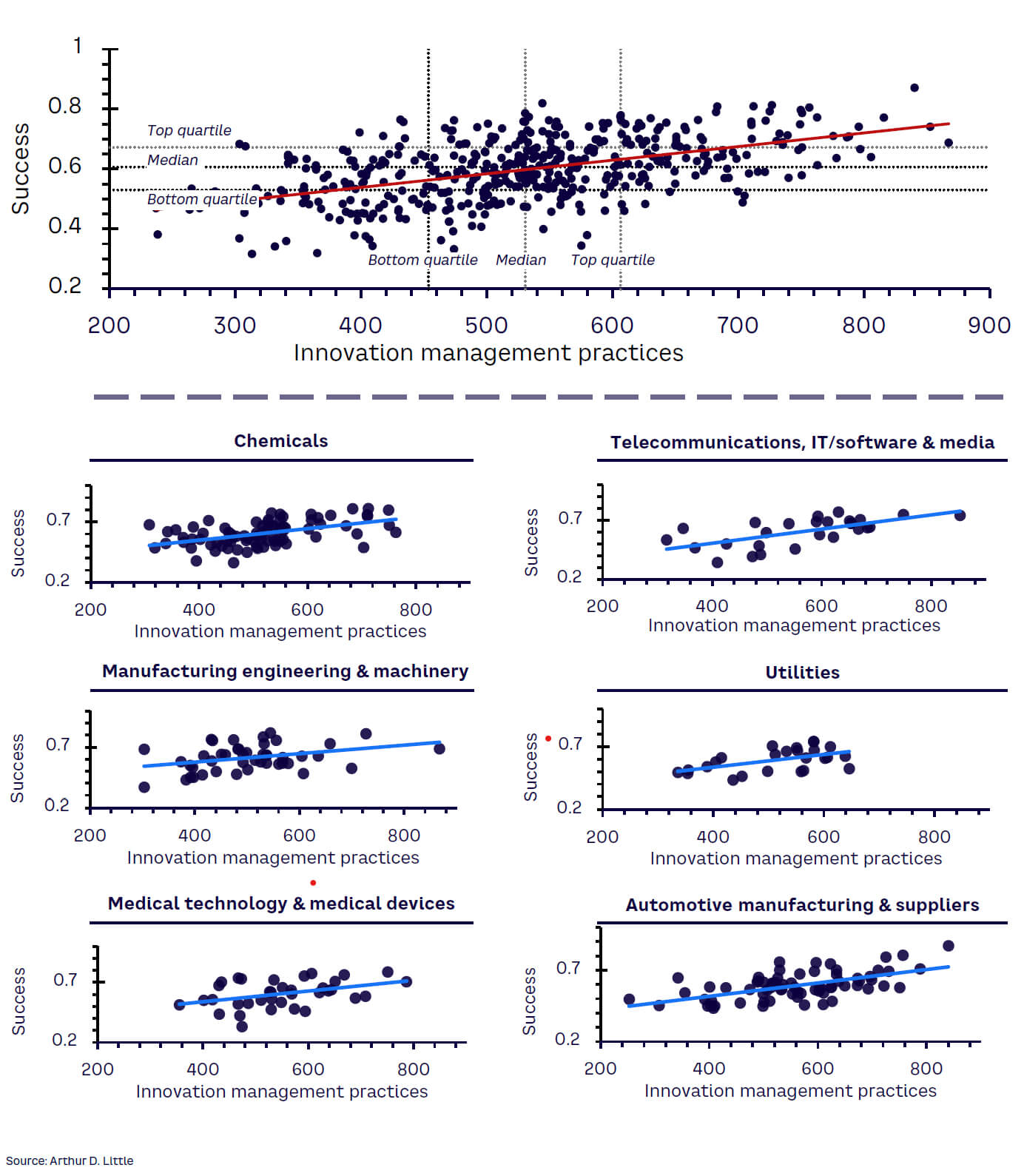

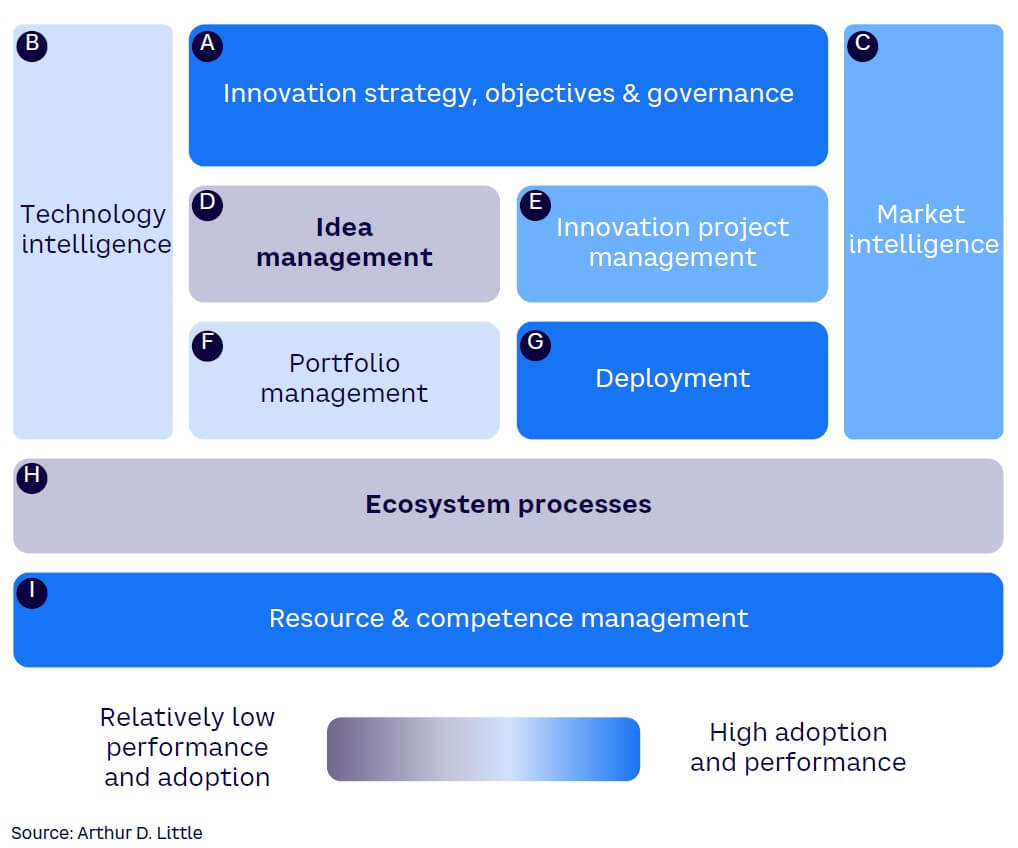

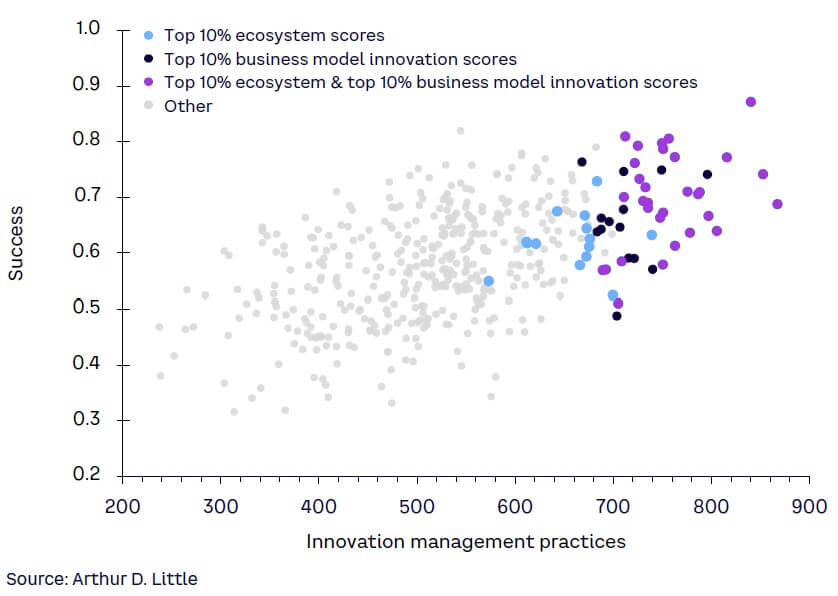

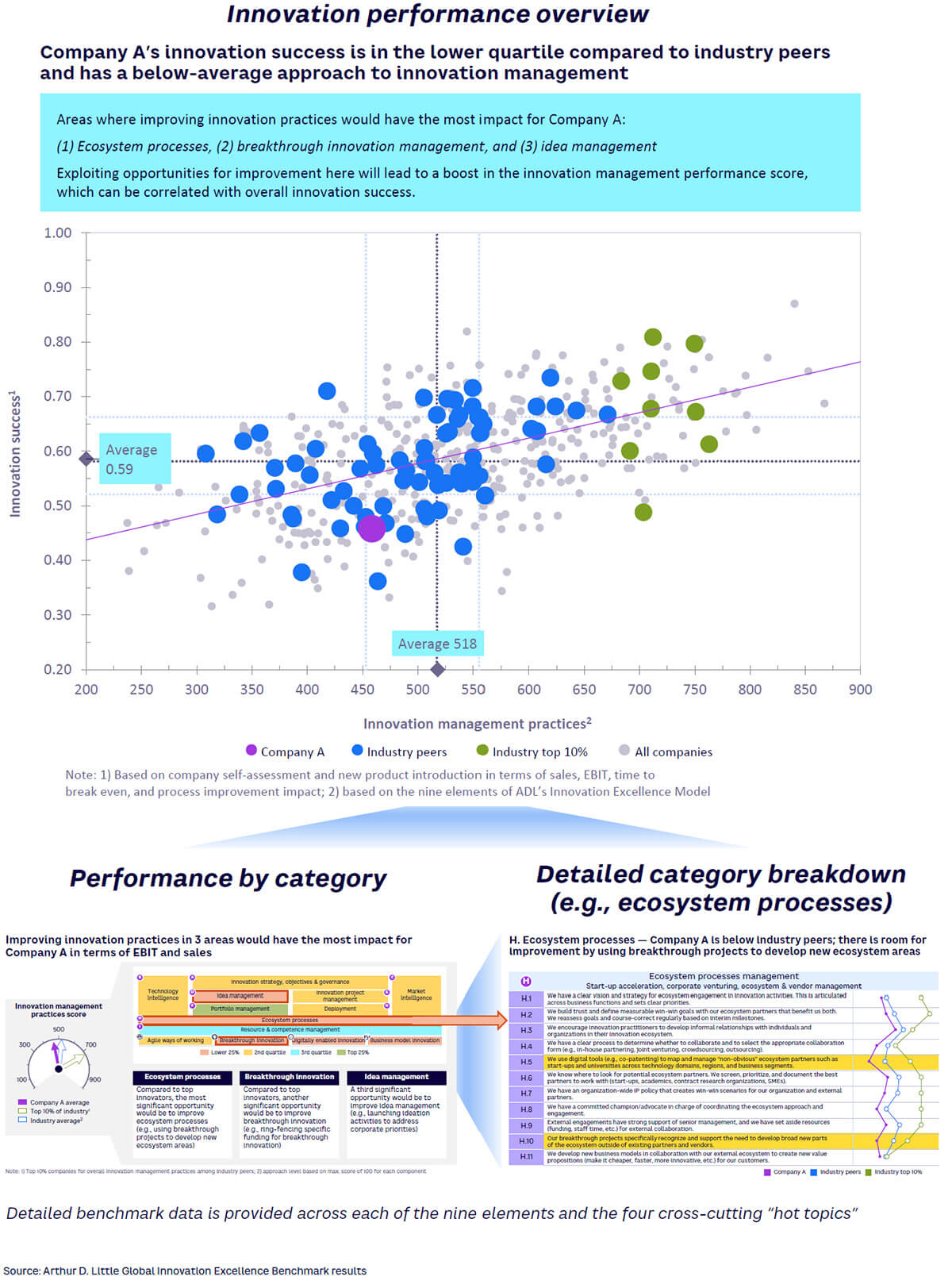

There is a clear link between good innovation management practices and innovation success. Previous studies have found a strong positive relationship between the successful deployment of innovation management practices of the Innovation Excellence Model and the innovation success they achieve (see Figure 1).[2],[3] This correlation holds true across all industries, despite the huge diversity in terms of products, services, customers, and industry-specific dynamics. Fundamentally, this pattern demonstrates that implementing effective innovation management practices can help companies attain greater success in innovation.

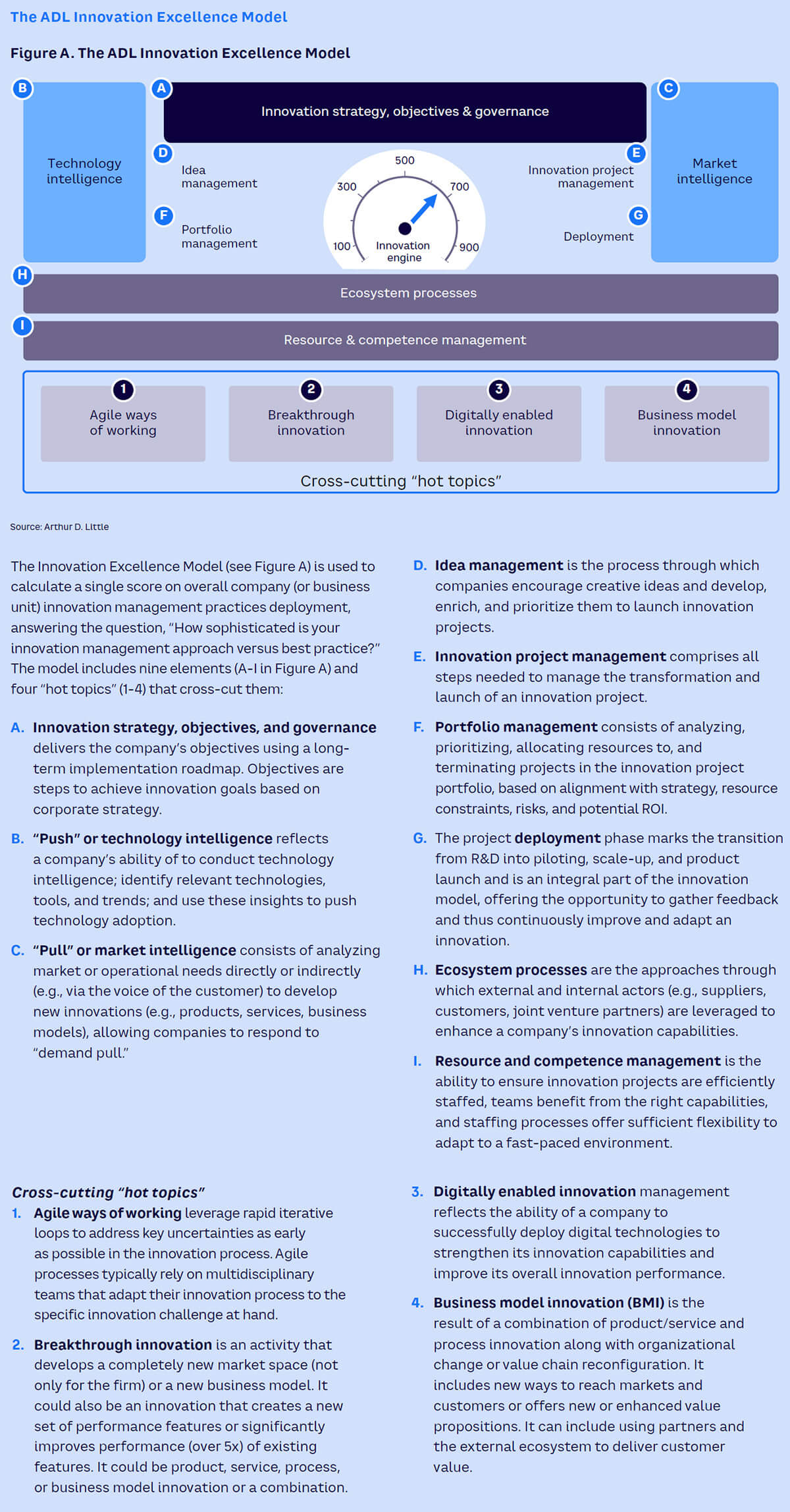

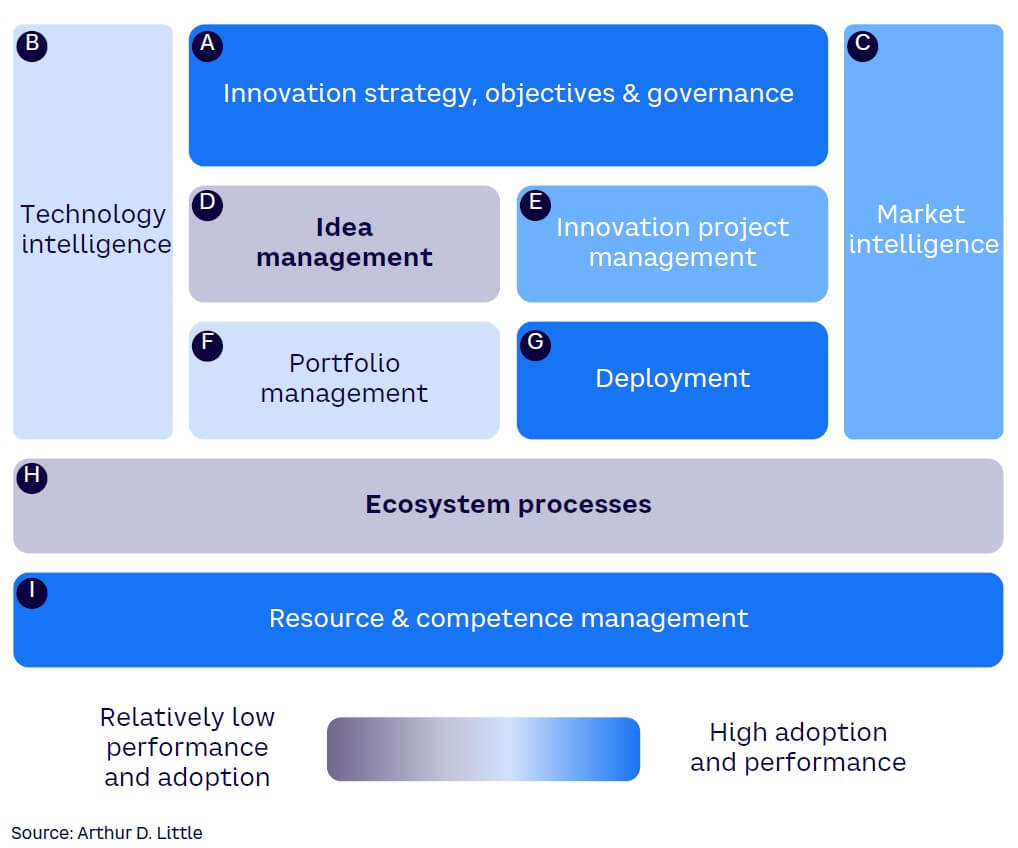

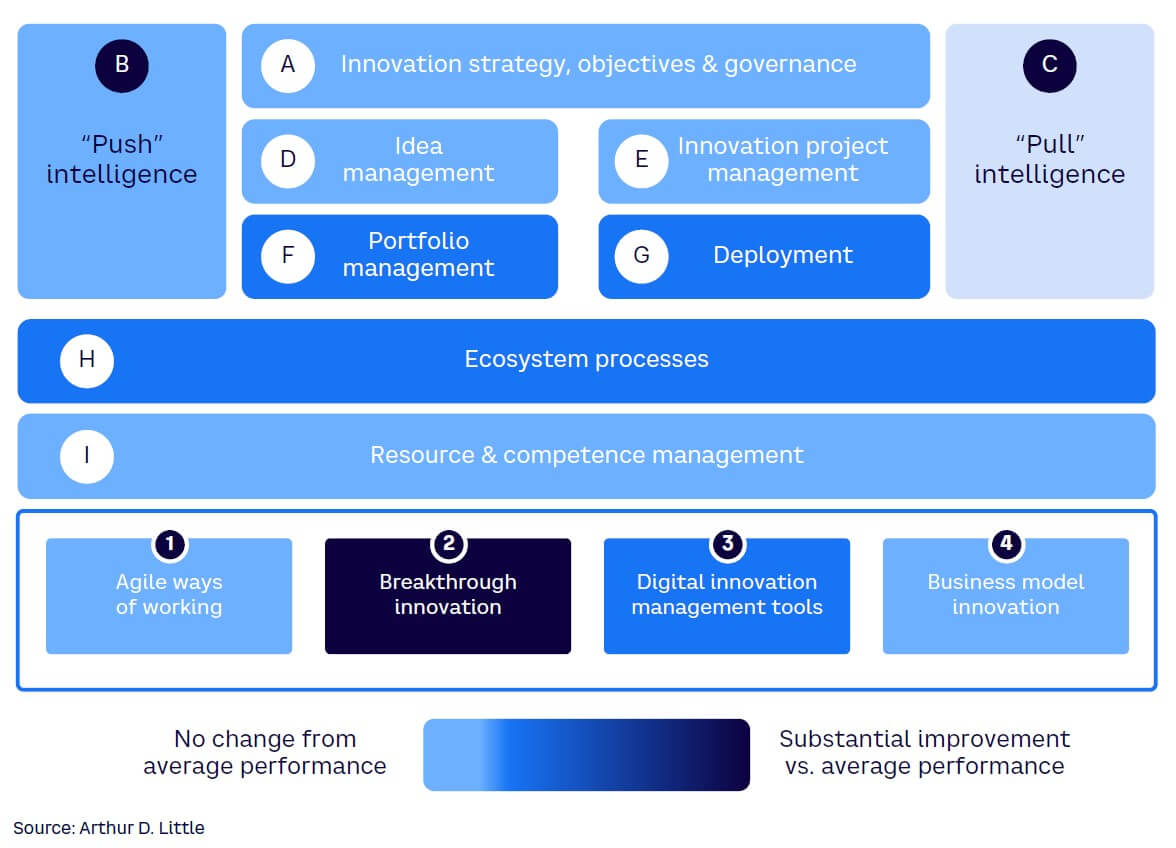

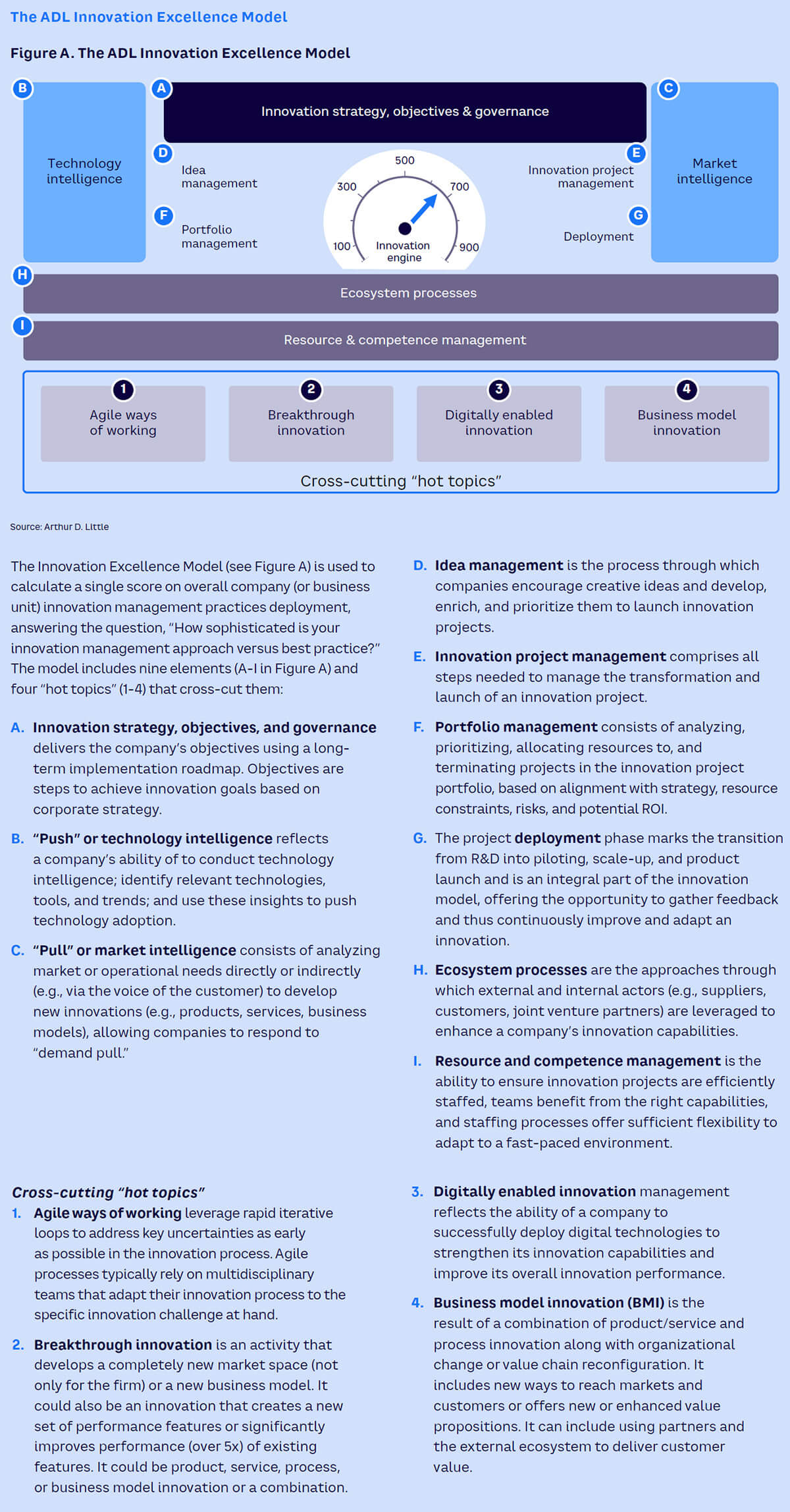

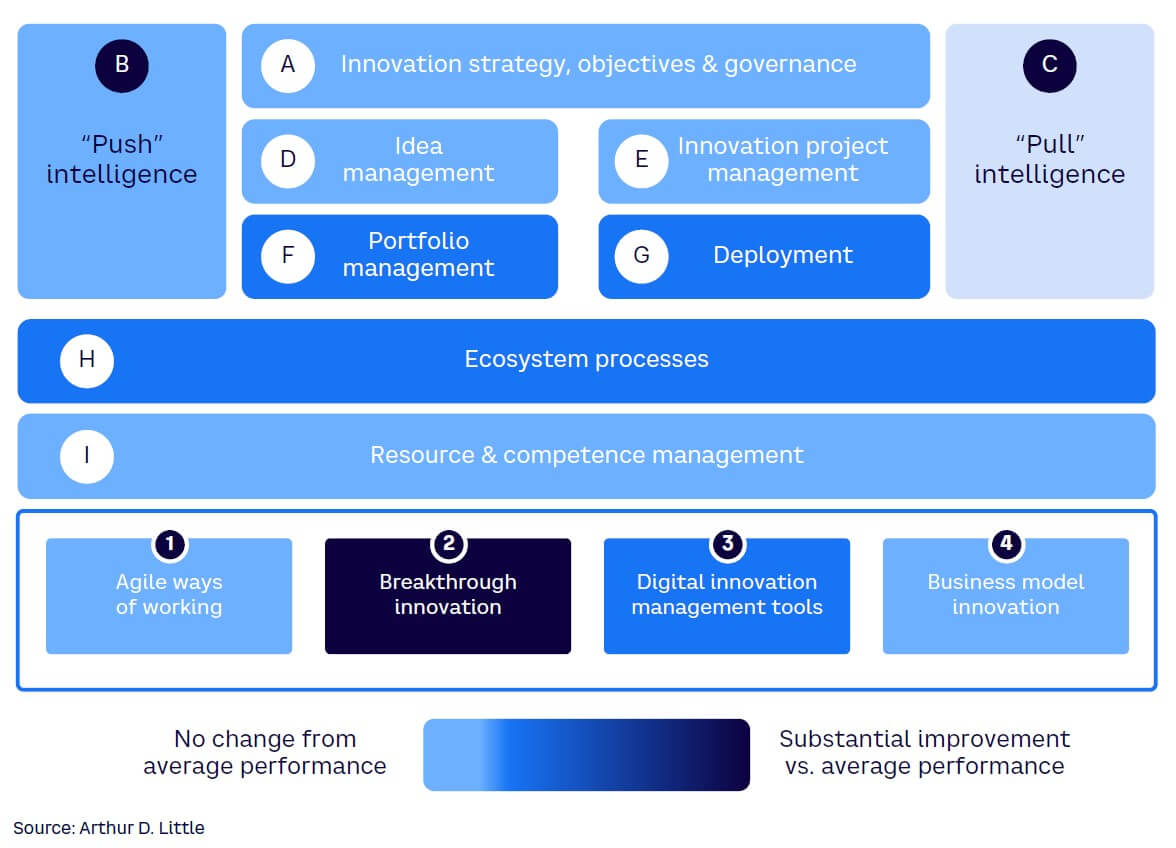

The GIEB covers more than 500 organizational units (companies and business units), breaking down their activities into the constituent components of the ADL Innovation Excellence Model.[4] This established model, validated in a range of peer-reviewed publications,[5] provides a framework to examine the different components of the innovation system and the innovation management best practices companies can adopt to achieve high performance in this area (see “The ADL Innovation Excellence Model”). The model measures:

-

Innovation management practices — how sophisticated your innovation management practices are versus best practices, assessing how well your company has implemented practices that contribute to the nine core elements and four cross-cutting themes of the ADL Innovation Excellence Model.

-

Innovation success — what your innovation effort delivers in terms of business impact. This is a composite score based on sales from new products/services/business models, the earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) from new products/services, the impact of innovation-related process improvements, time to breakeven, revenue generated from breakthrough innovation, and management satisfaction with innovation performance. Importantly, we normalize responses for the different components of innovation success by industry or by peer group because margins and time to breakeven, and so on, vary significantly by industry.

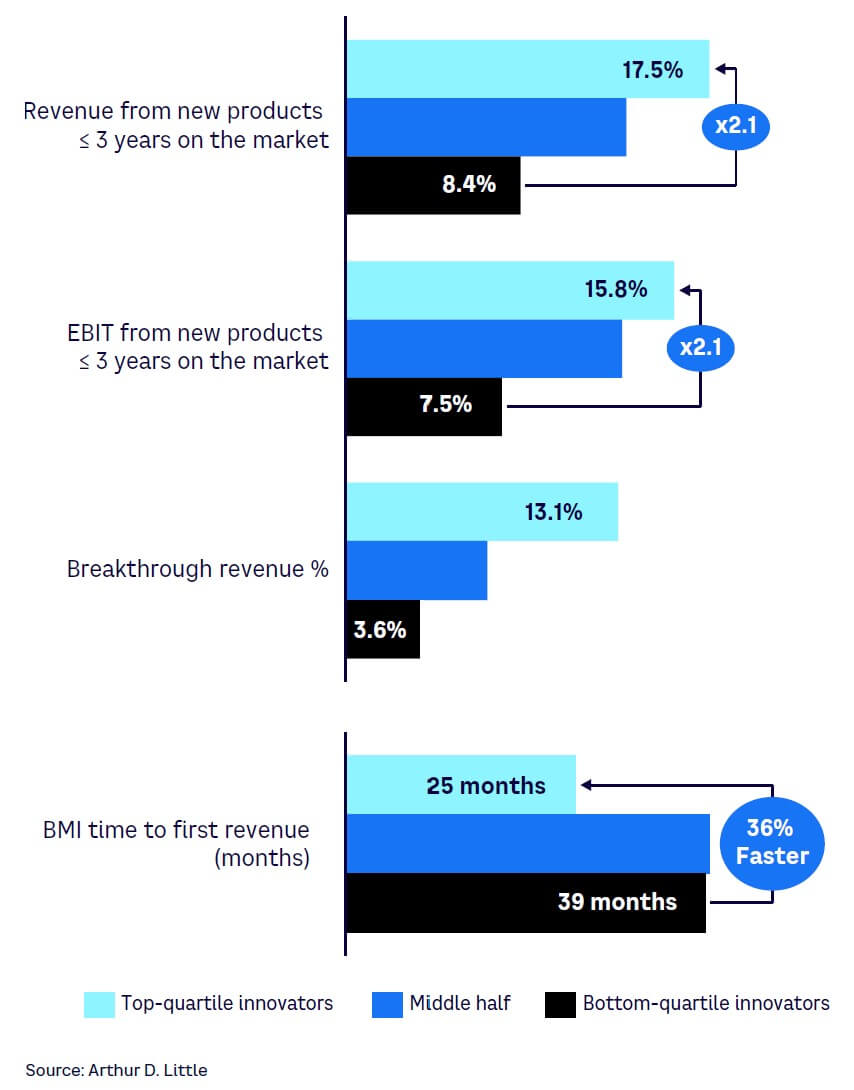

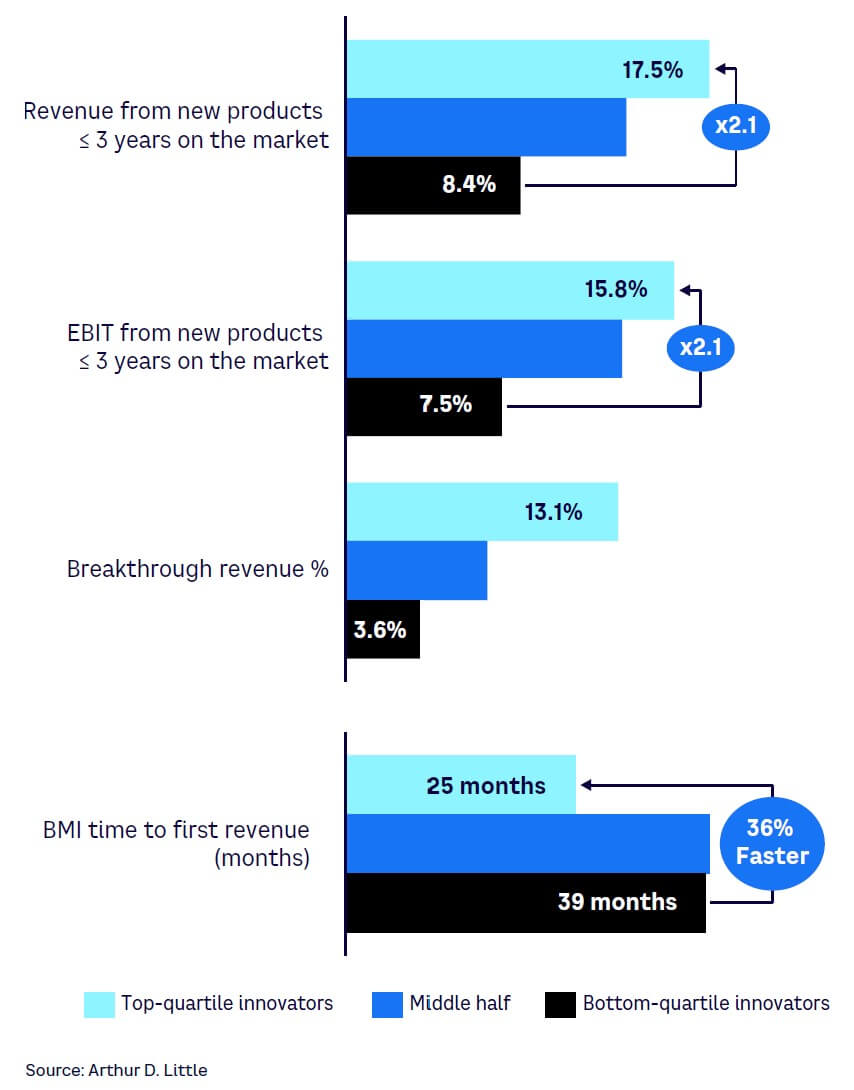

As shown in Figure 2, top-quartile innovation management practitioners realize an average of 9% points’ difference (56% more) in EBIT from new products and services (≤3 years on the market) when compared to peers with bottom-quartile innovation management practice scores in the same sector. Top-quartile innovators also realize an average of a 9% point difference (in share of 2.1x more) turnover from new products and services players and use 36% less time to reach breakeven from their investments in business model innovation.

This range of performance demonstrates the huge opportunity cost for those not currently in the top quartile. With ample scope to improve on their innovation performance, these practitioners can dramatically increase their business success, and by learning from their peers and other industries and adopting proven best practices, they can elevate their innovation scores.

For example, within the chemical industry benchmarks, the most innovative company achieves a score of 763 out of a possible 900 for innovation excellence, while an average performer will achieve around 513. If that average chemical company improved to achieve top-quartile innovation returns for products with less than three years on the market, it would improve its EBIT from new products by up to 8% points, assuming it followed the same overall trend we see in responses. When we consider the enormous continued investment required for new products and services, this suggests that a lot of money is being left on the table in terms of improvement potential.

The BlackRock Investment Institute did an interesting piece of analysis comparing total shareholder returns of various types of capital usage, including R&D, in the Russell 1000 Index (see Figure 3). In the long run and on average, BlackRock found R&D to be a better use of investment than, for instance, CAPEX or acquisitions.

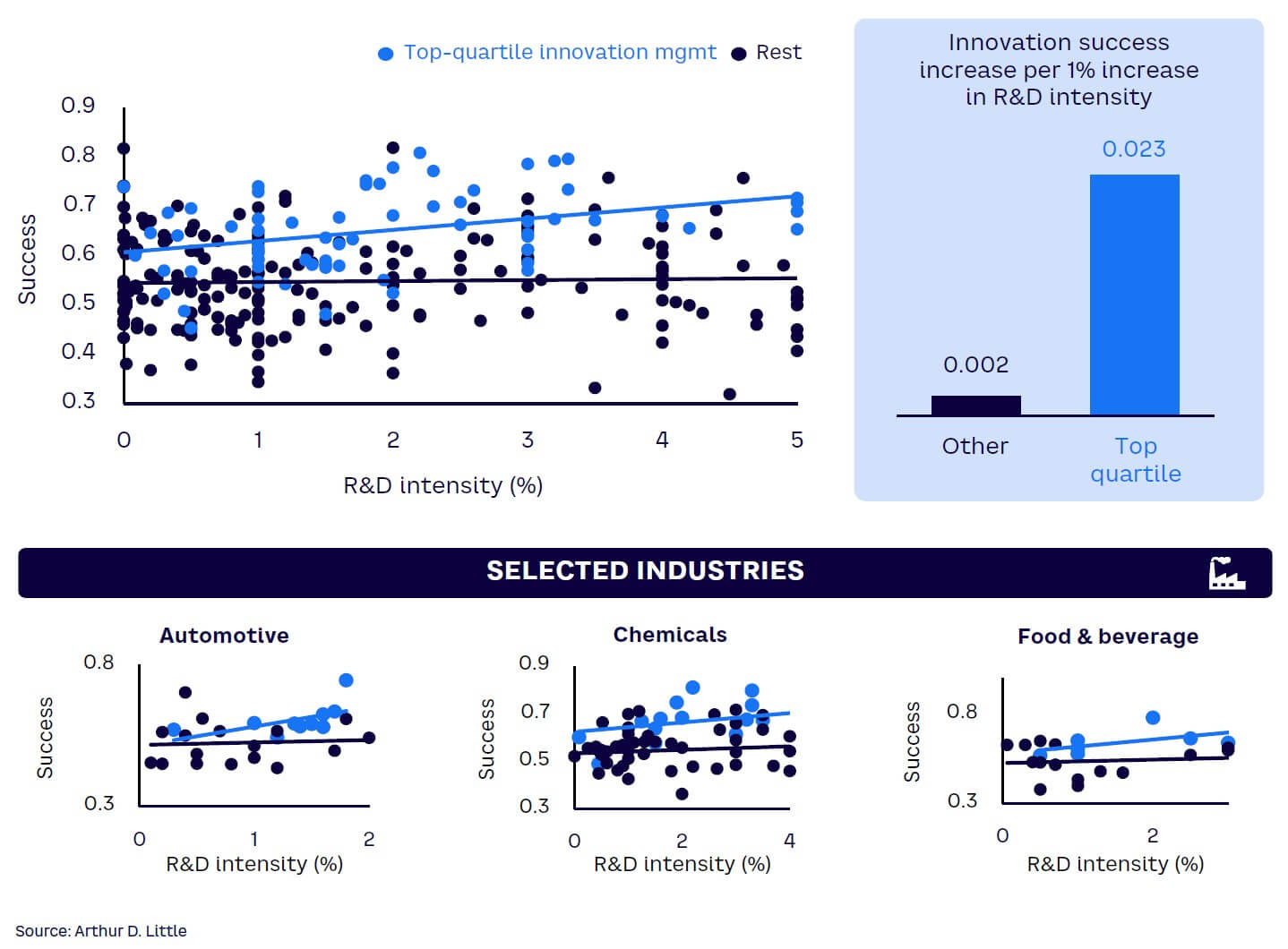

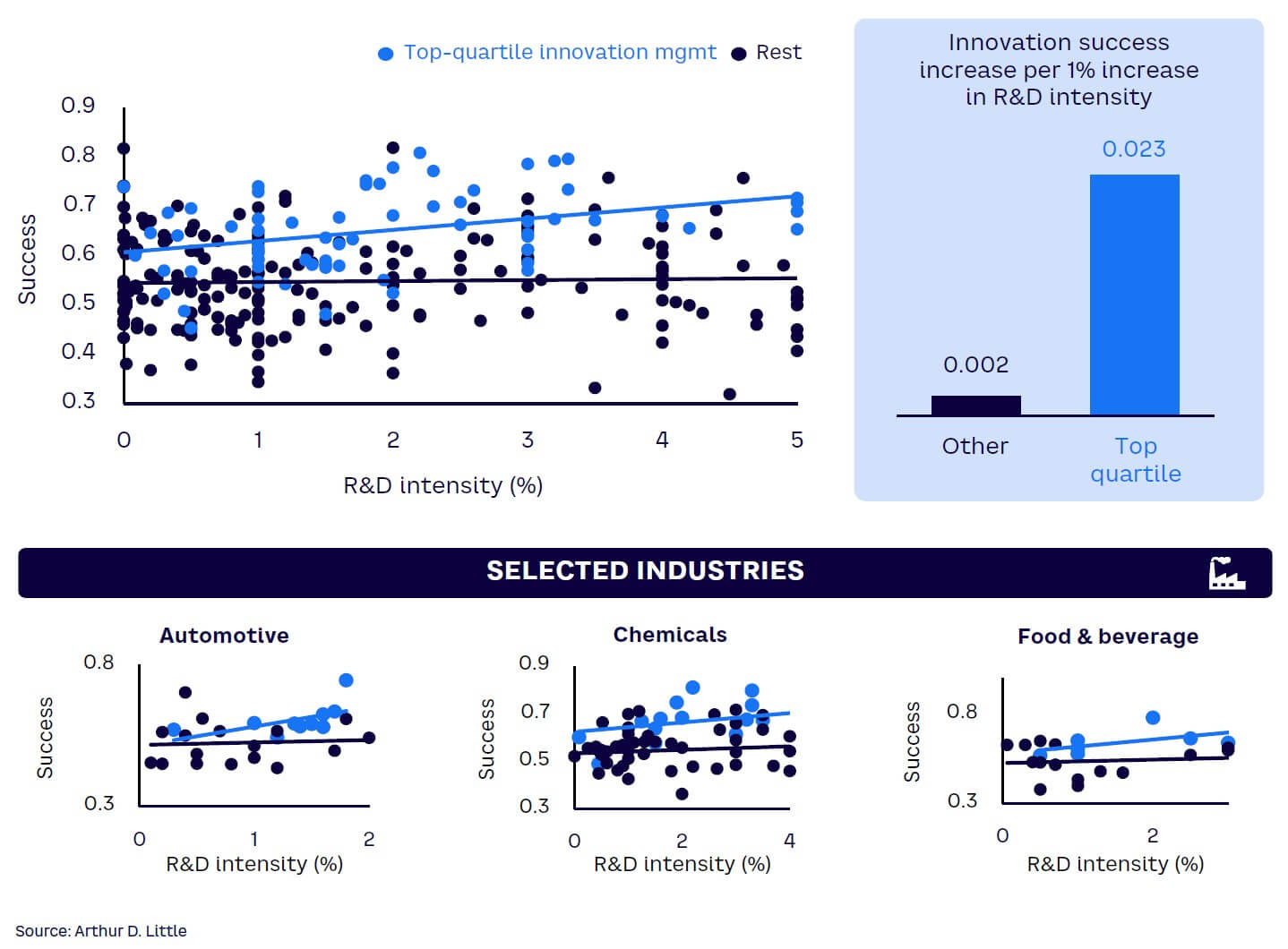

For an organization struggling to see returns on innovation investment, allocating additional resources to R&D departments thus may seem like a practical solution. Many studies claim a clear link between investing in R&D and firm performance. However, ADL’s latest analysis shows that this is not as straightforward as previously thought.

Across industries, the data shows no significant correlation between R&D intensity and innovation success. The view changes when we focus on the organizations with the best innovation management practices (see Figure 4). These companies, which display top-quartile innovation management practices, show a clear relationship between the level of investment and the company’s return (innovation success); a pattern that holds true across industries but importantly does not hold true for companies outside the top quartile that would waste any increased investment in further R&D.

BEST PRACTICES DIFFER BY INDUSTRY

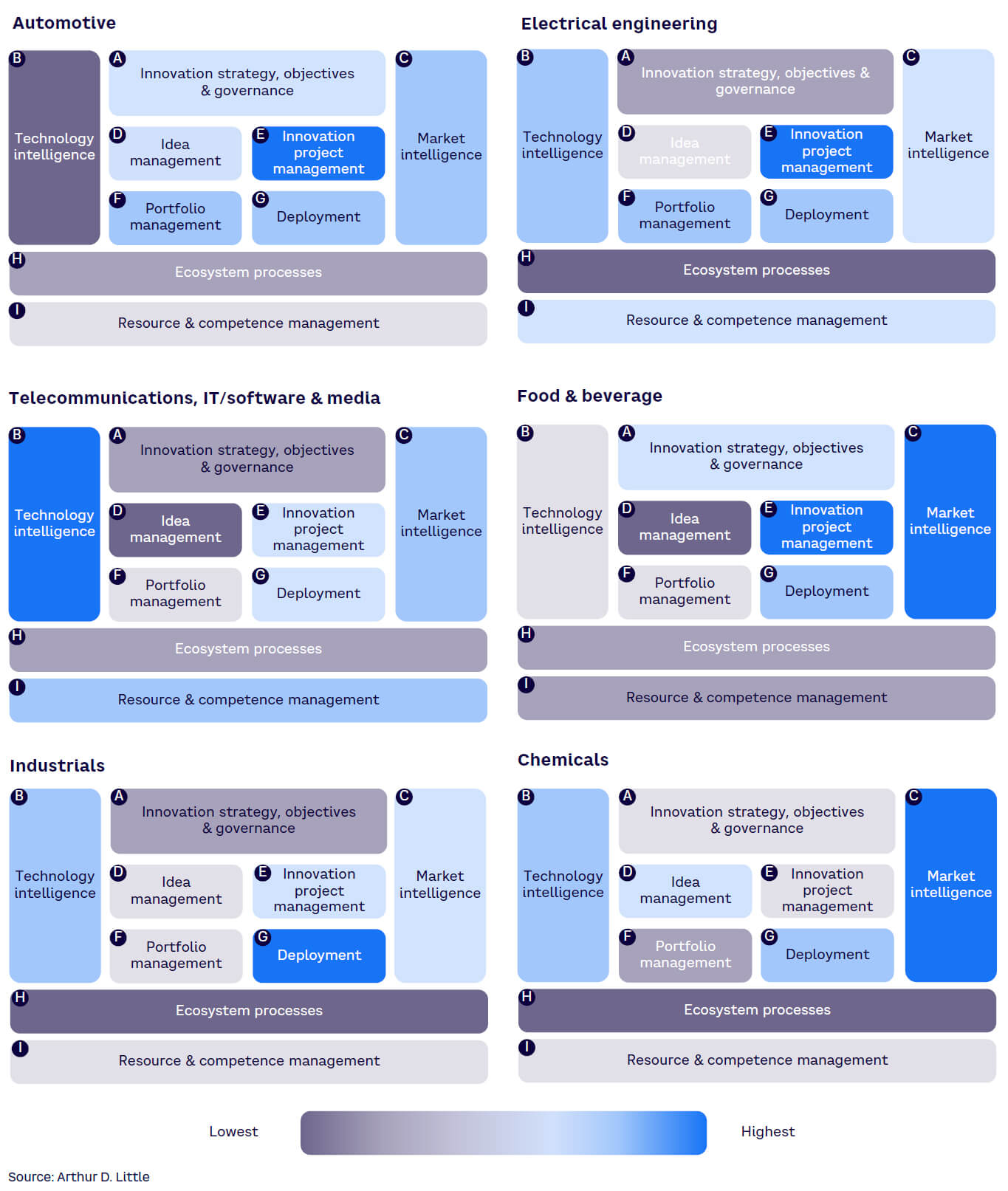

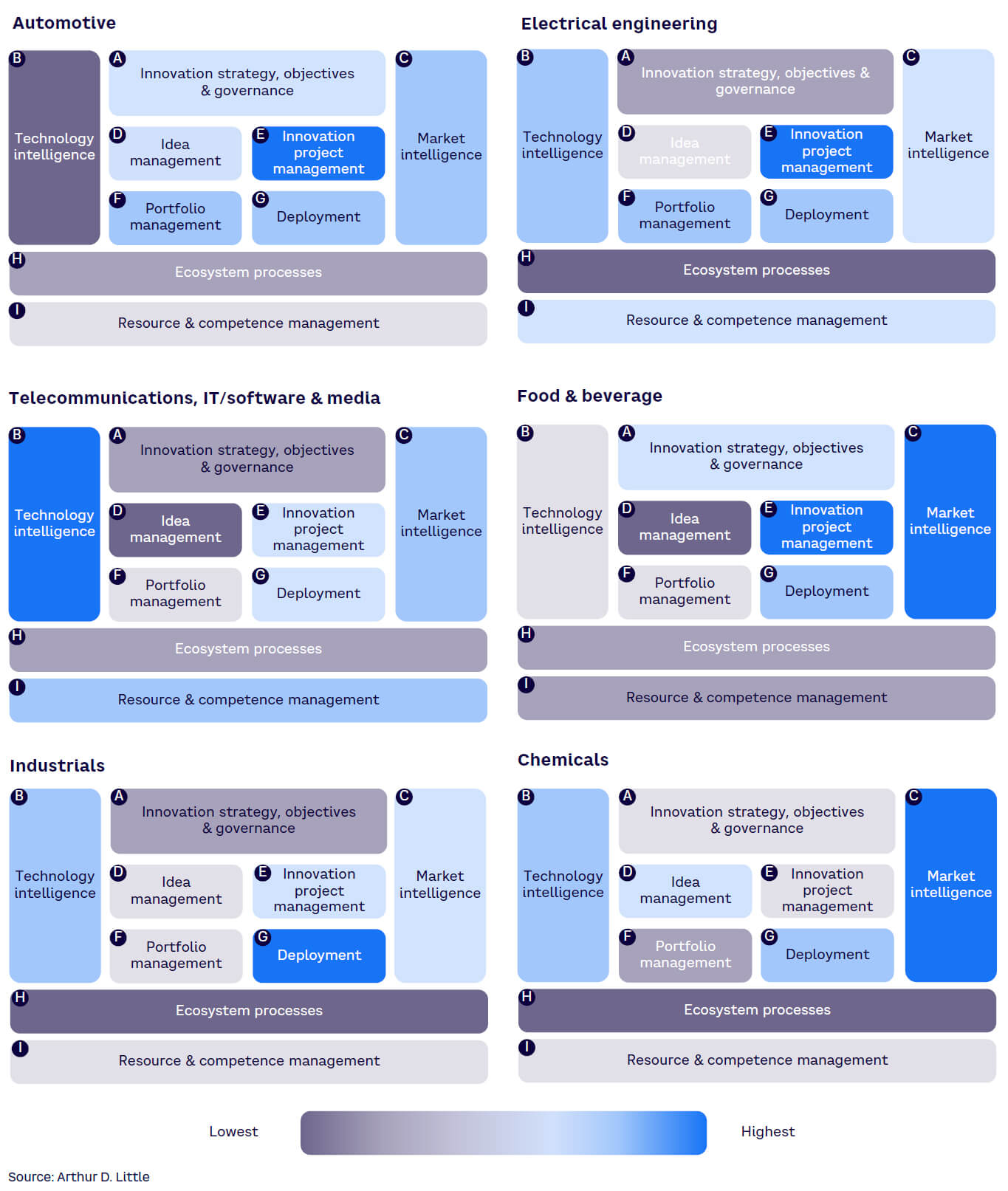

The relative importance of the elements behind innovation success clearly vary among industries. You cannot expect innovation processes within a food and beverage company to be identical to those of a heavy industrial company, for example. ADL’s model takes these differences into account using an approach based on sector data to normalize performance between sectors and to provide peer-to-peer comparisons.

While the model is relevant across all industries, there are some differences between sectors in terms of the elements of the model that are most important and have the highest impact on innovation success. To understand these differences, we asked benchmark participants to rate the relative importance of a variety of elements (see Figure 5). In analyzing these responses, it becomes clearer which elements are perceived to be most significant as well as how their relative importance relates to the nature and dynamics of the industry. Findings included:

-

For virtually all industries, technology and market intelligence are highly valued. In particular, telecoms highly value technology intelligence, reflecting the transformative nature of fast-moving technology trends within these two sectors (notably digital technologies and a shift toward sustainability).

-

Automotive, electrical engineering, and food and beverage rate innovation project management most highly. This corresponds to the broader importance of process and efficiencies in these industries, which typically use tools such as Lean Six Sigma, Kaizen, and Total Quality Management and focus on innovating for value.

-

Food and beverage companies also attach high importance to deployment and rollout. Given that product development cycles in this sector can be less than three months, marketing innovation is often more important than technological innovation, and time to market is critical. This all reinforces the importance of fast rollout to innovation success.

-

The automotive sector rates portfolio management as an important element, reflecting the significance of product platforms in the industry, the focus on creating dedicated portfolios of products to meet fast-evolving customer needs, and the complex technologies required to support product development.

-

The chemicals sector places a relatively strong emphasis on idea management, reflecting the importance of end-to-end product development in the sector and the adaptability needed to supply a diverse and dynamic customer base. Pull, or market intelligence, is also valued, particularly around customer willingness to switch supplier/product and to pay more for innovation.

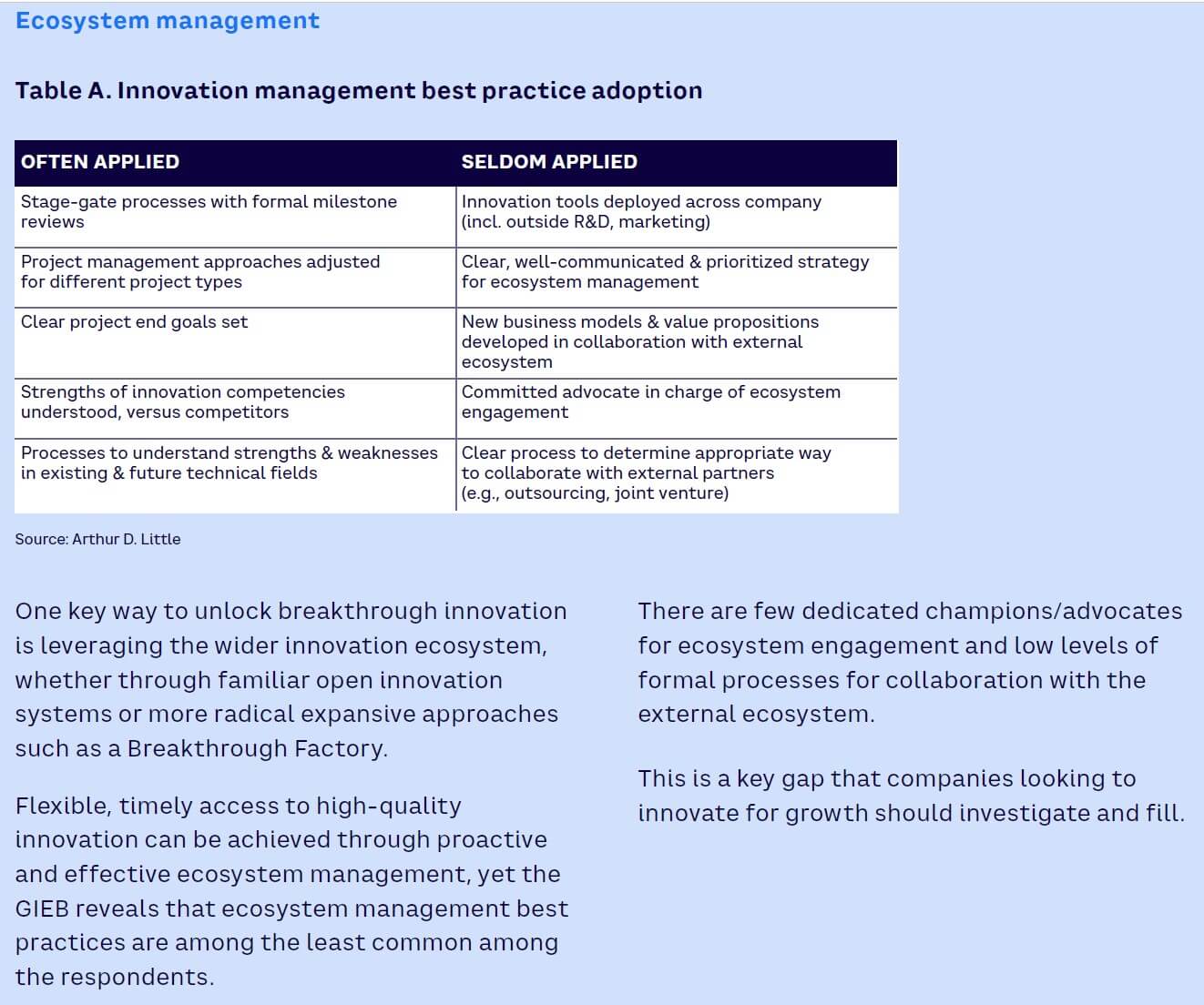

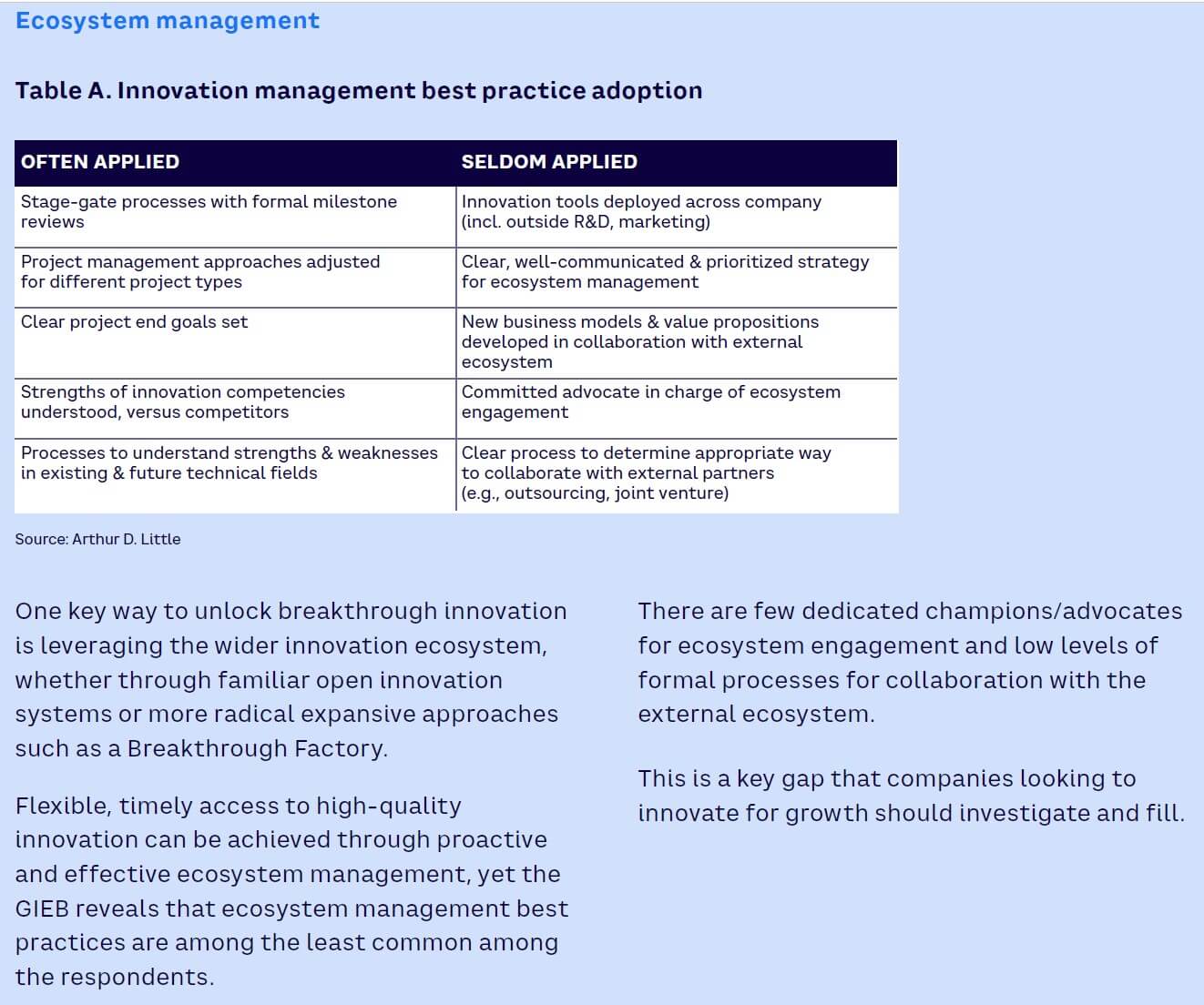

Despite the differences, some categories of innovation management processes are equally important to all industries. Many of these practices, such as ecosystem approaches and business model innovation, remain underused across industries, as illustrated in Figure 6, providing a clear opportunity for deploying these to increase performance.

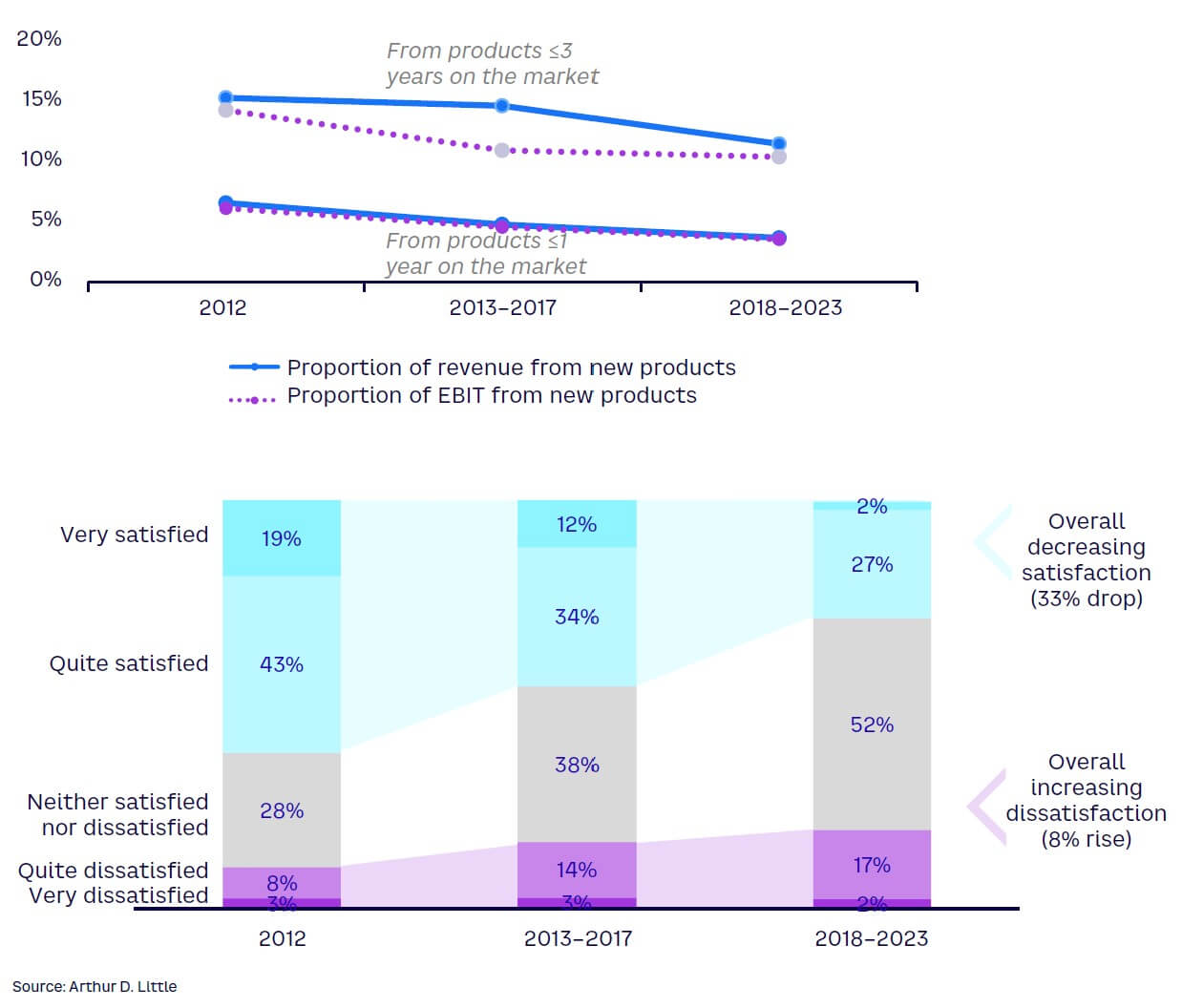

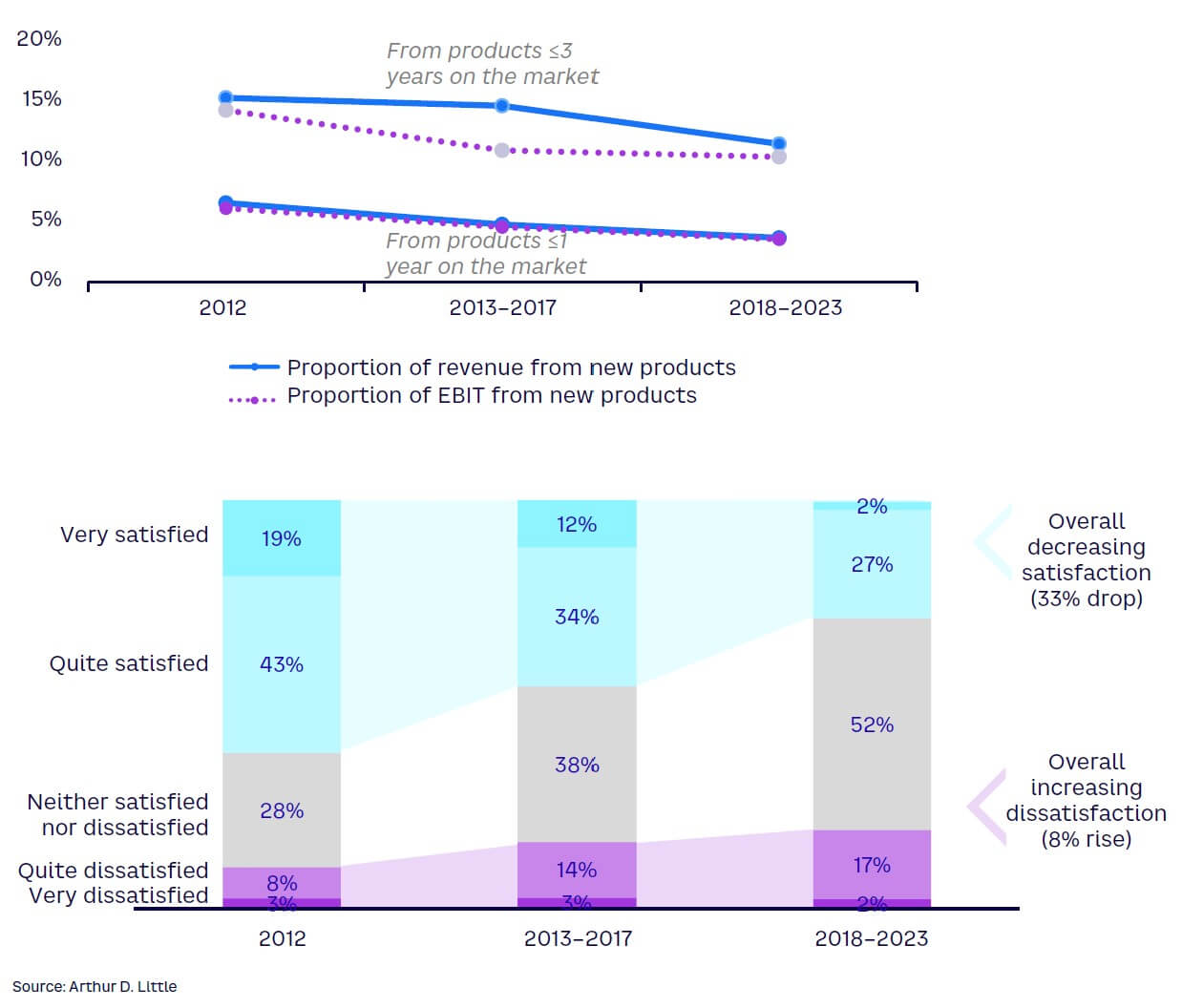

INNOVATION PERFORMANCE SATISFACTION DECLINES

Reported financial returns from innovation have fallen across a range of business metrics since 2012, as illustrated in Figure 7. This drop, combined with other factors such as digitalization and technology convergence, is driving increased complexity and making innovation beyond the core harder. This has led to a corresponding increase in the number of companies reporting an average or low level of satisfaction with their innovation investments (see Figure 7). In fact, just over a quarter (29%) of recent respondents say they are satisfied with their innovation performance, falling from 62% in 2012. According to ADL analysis, factors impacting innovation success include the increasing cost of innovation, lower risk appetites (leading to a higher focus on incremental innovation instead of transformative breakthrough innovation), and the maturation of many markets. The failure to fully engage with customers, suppliers, start-ups, universities, and the wider ecosystem of innovators to drive growth is especially noteworthy.

Altogether, the GIEB data suggests that traditional innovation practices are not delivering the same benefits as they provided in the past. There is a clear need for new practices to meet the requirements of a changing, evolving world. Importantly, this downward satisfaction trend can be reversed because underperforming practices across industries (refer back to Figure 6) can be targeted to increase R&D efficiency.

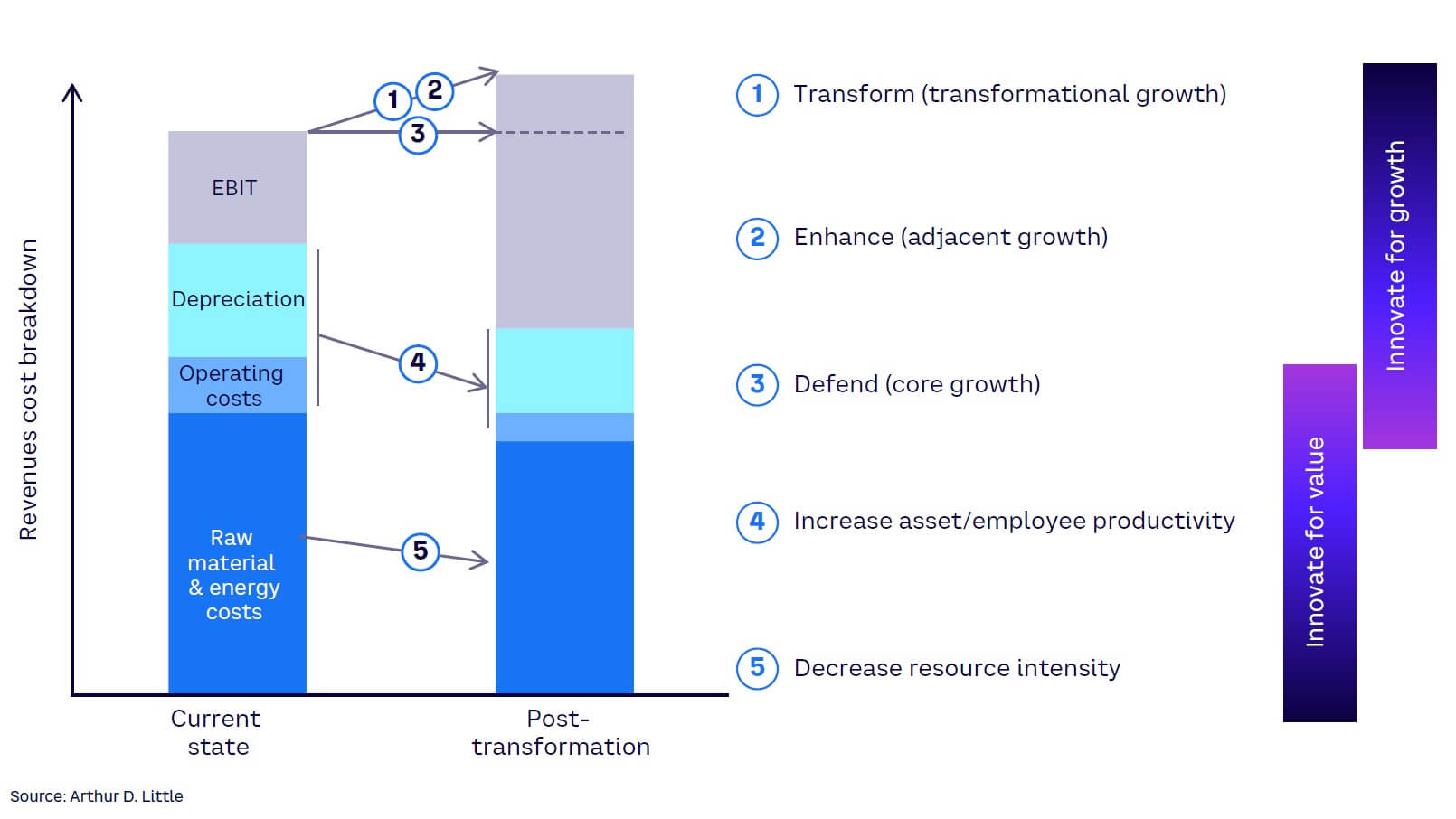

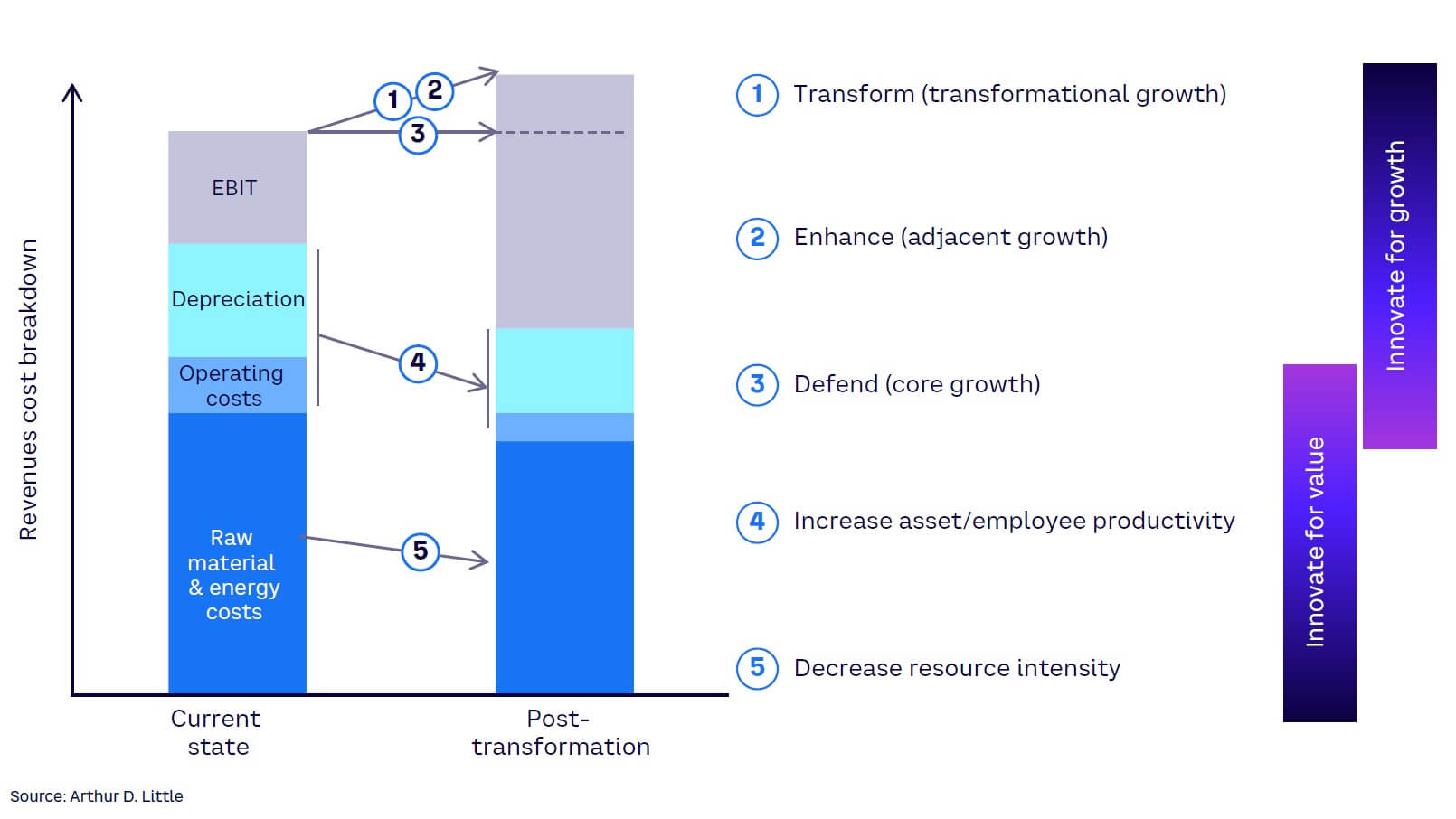

The ADL model highlights the benefits of taking an integral view of innovation management to realize growth and value creation. Figure 8 summarizes the main five options in two main areas of innovation:

-

Innovate for growth — focusing on profitability through defense, enhancement, or transformation. Approaches include new products, services, and business model creation; the development of the innovation ecosystem; solving challenging problems; and developing entirely new businesses via breakthrough innovation. Breakthrough innovation (described in Chapter 2) and Agile innovation (see Chapter 5) are two practices organizations can adopt to focus on innovating for growth.

-

Innovate for value — focusing on core growth, productivity, or decreasing resource intensity. Approaches include understanding technology needs and designing dynamic innovation strategies, optimizing productivity, and delivering cutting-edge innovation capabilities. The simplest way for large organizations to innovate for value is to isolate areas of good practice internally, via cross-business unit innovation analysis and harmonizing/optimizing innovation management practices (see Chapter 4).

Alongside these approaches, business model innovation (see Chapter 3) spans both growth and value.

2

INVESTING IN BREAKTHROUGH INNOVATION TO IMPROVE PORTFOLIO PERFORMANCE

by Dr. Habib Hussein, Simon Norman, Philipp Mudersbach, Dr. Arnaud Siraudin, Kerstin Widmann, Rick Eagar, and Ben Thuriaux-Alemán

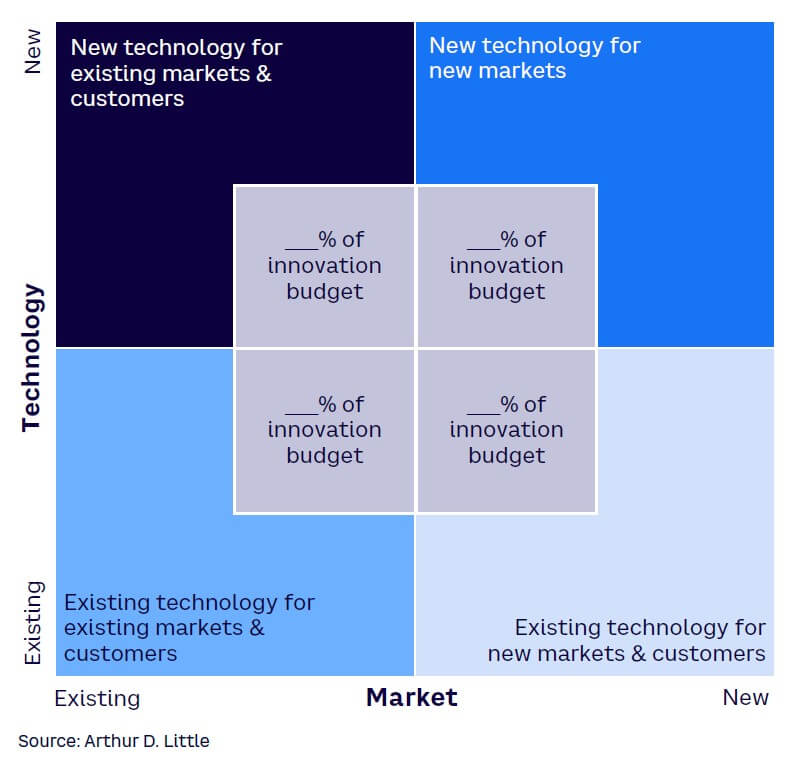

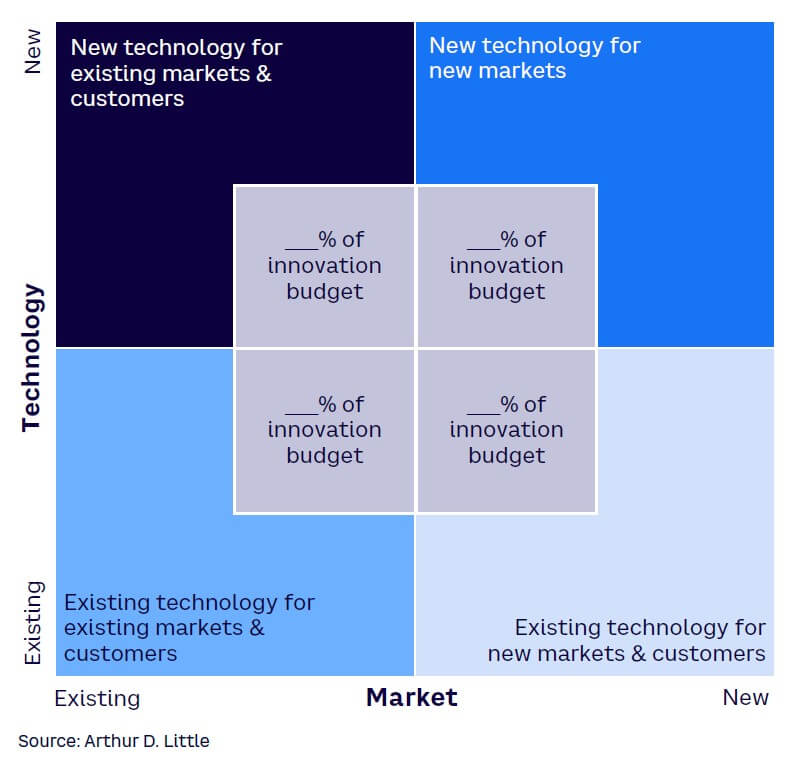

It is widely acknowledged that successful organizations use a well-balanced innovation portfolio to drive future growth (see Figure 9). However, short-term targets, poor innovation management processes, risk-averse senior management, and other factors mean that many companies still heavily weigh their innovation portfolio toward incremental or step-change innovations with very little emphasis on breakthrough innovation as a growth lever.

Many executives fail to properly balance the notion that disruptive innovation endeavors are more likely to fail against the upside that they may provide a new space for the company to thrive, fostering long-term success and survival. Unfortunately, cognitive bias toward near-term, less risky, smaller returns has the tendency to win out, and unless significant effort is applied, CTOs often find themselves overprioritizing incremental innovations with more reliable returns in the short term.

In fact, ADL’s latest research shows that those companies that proactively invest more on “riskier” innovation endeavors, building out new technologies in new markets, have higher company innovation success scores.

Breakthrough innovation is often closely tied to the new technology-new market quadrant shown in Figure 9. Breakthrough innovation can be defined as an activity that develops a completely new market space (not just new for the firm) or a completely new business model. It could also be an innovation that creates an entirely new set of performance features, significantly improves performance by over five times compared to existing features, or reduces costs by more than 30%. Breakthrough innovation spans all innovation categories — it can be a product, service, process, or business model innovation, or a combination of these.

There is a myth that breakthrough projects have higher risk. In fact, this depends on your perspective. If risk = uncertainty x cash flow exposure, then there is limited risk in breakthrough projects because the downside is limited to the innovation project cost. The real source of risk is missing out on the upside of a market opportunity. But it is true that breakthrough projects have inherently higher uncertainty (and higher rewards). As a result, they require a different set of innovation management processes, a different set of stakeholders, and different metrics and monitoring criteria. ADL data shows that those who score highest for breakthrough innovation management clearly differentiate between breakthrough and incremental innovation and manage them differently. Leaders ensure that their portfolios are clearly split — and that their innovation strategy sets out explicit boundaries, expectations, and resources — for breakthrough innovation versus incremental innovation.

Analysis of the GIEB shows that strengths in breakthrough innovation deliver two key benefits:

-

Those companies that have allocated a portion of their budget specifically to breakthrough innovation projects reap better results, generating greater revenues from disruptive new products, services, and business models.

-

Higher returns from breakthrough innovation correlate positively with overall higher innovation success. Companies where breakthrough innovations make up more than 5% of revenues have an average innovation success score of 0.61. In comparison, companies where 0%-5% of revenue comes from breakthrough innovations have an average innovation success score of 0.53. The implication is that better breakthrough success leads to better overall innovation success.

INVESTING IN BREAKTHROUGH INNOVATION

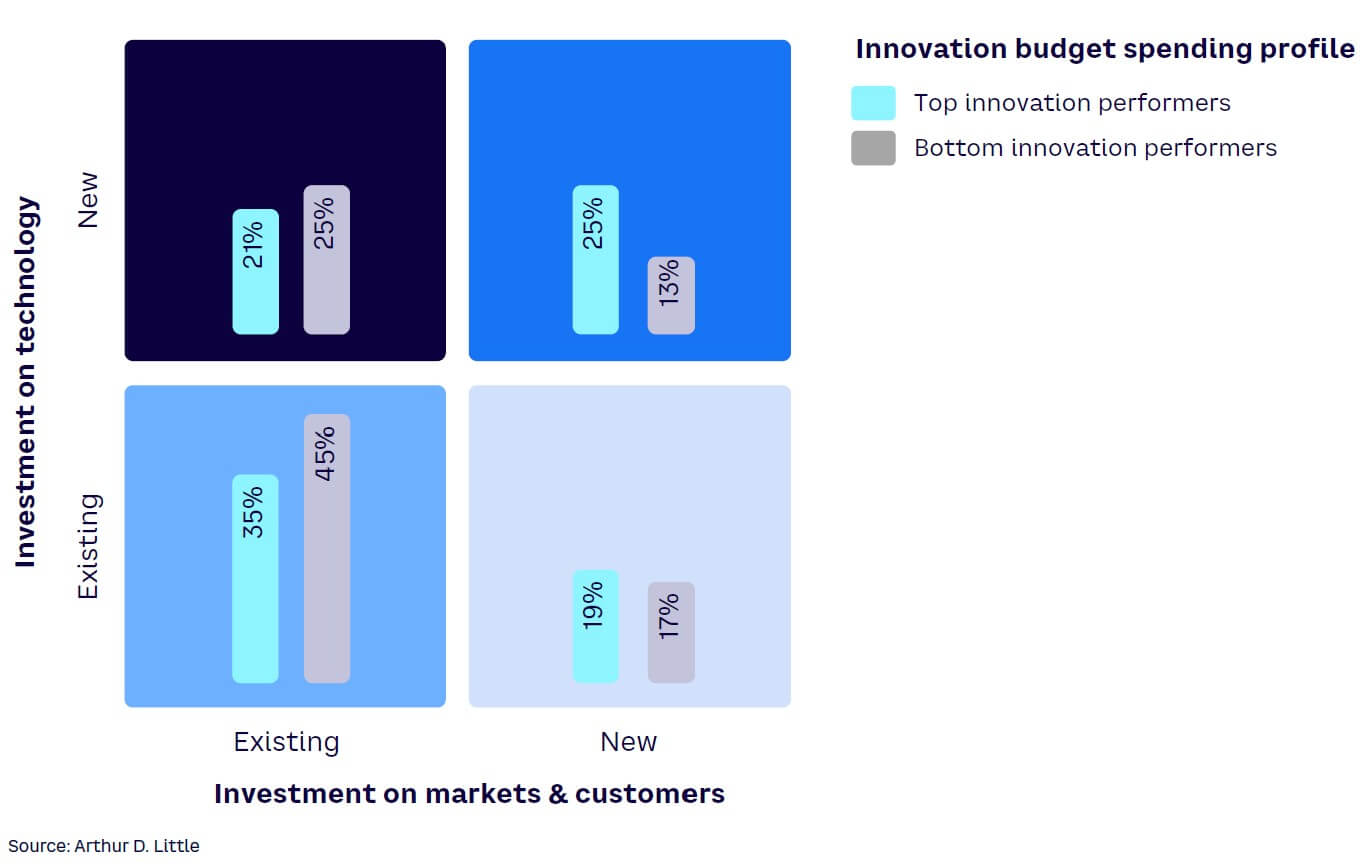

The results of ADL’s analysis indicate that there is a clear link between where companies invest on innovation and their overall success:

-

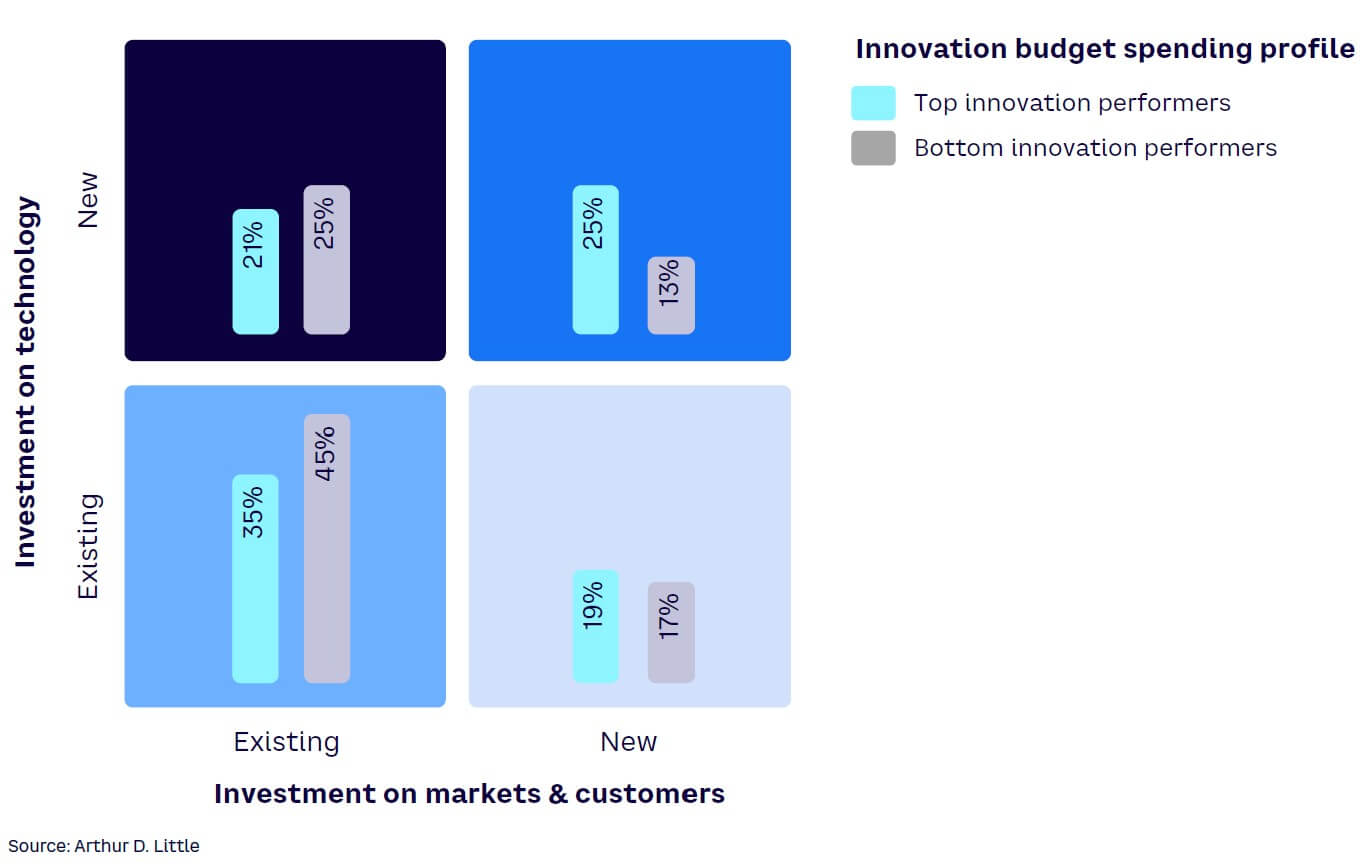

Those that have a clear focus on breakthrough innovation as part of their innovation strategy generate on average a better return on innovation investment. The data shows that those companies with the best innovation success scores, with the highest revenue and EBIT from new products and services, spend proportionally more of their budget on breakthrough innovations (see Figure 10). Essentially, focusing more on new technologies in new markets leads to greater benefits from innovation investments over the medium to long term. Extending existing technology to new markets can also generate a higher-than-average return on innovation. However, global firms have often reached the limits of entering new markets and this is then only viable for companies that are still expanding geographically.

-

Companies that invest in breakthrough innovation spaces are better overall at delivering innovation. Simply investing in new technology for new markets is not enough to deliver significant results. You need to spend money in the right areas and have the right innovation management practices in place, otherwise you are wasting your investment. Figure 11 shows that the top 25% of companies that successfully implemented breakthrough innovation that facilitates them entering new markets with new technologies score correspondingly higher in deployment of innovation. This highlights the importance of considering and involving the entire innovation value chain to ensure that the gaps from idea to technology to product and market success are bridged.

Our analysis indicates that those companies that invest more in new technology and new markets display breakthrough innovation management practices 16% above the average. Companies that spend the most on developing for “new markets, new technologies” also invest on average 28% more on breakthrough innovation compared to others.

This is logical, as strong innovation management practices correlate with higher success, which in turn will give leadership teams and decision makers greater confidence in investing in higher-uncertainty projects.

WHAT UNDERPINS BREAKTHROUGH INNOVATION SUCCESS?

Our analysis indicates that a focus on breakthrough innovation is a key tool of companies focused on innovating for growth and a critical underpinning component that contributes to overall higher innovation success. However, creating the foundations for serial breakthrough innovation is challenging and involves focusing on six key success factors:

1. A clear strategy & senior management support

To complement bottom-up ideation for detecting disruptive concepts, it is generally useful to add a top-down approach. To succeed in this new era, companies must find platforms of stability and consistency to allow them to fully leverage their investments and resources in an agile, flexible, and dynamic way. They must also be able to communicate this purpose and direction to the markets and to their own staff, including full senior management support.

To meet these challenges, ADL has developed a methodology called “Innovation Purpose” for aligning R&D around innovation.[6] The methodology consists of answering the following questions:

-

Why keep R&D rather than “nothing”?

-

In which business attributes should we be the best in terms of customer value?

-

In which associated technologies should we invest?

-

How do we define our R&D DNA to be at the leading edge of our markets?

The Innovation Purpose approach engages R&D in a natural transformation process, clarifies the benefits it brings to the business, and helps select the technologies needed to develop breakthrough concepts and optimize resources while leveraging the innovation department’s culture and working methods.

Breakthrough innovation will not happen without a clear, well-defined strategy that explicitly states the commitment to this type of innovation and sets meaningful investments and clear goals. The more explicit the goals are, the greater the likelihood of achieving success. Goals can be derived from both the high-level innovation purpose defined by the organization and in response to trends/disruptions picked up through a “Future of X” study. Given the nature of breakthrough innovation, that means high uncertainty and often longer development timelines, senior-level commitment, and a full investment plan are required to provide the resources and focus to follow through on these projects.

There should also be a commitment to engage external partners such as customers, suppliers, and universities. In addition, corporate venture capital (CVC) investments in start-ups can serve as seeds for breakthrough innovations, and M&A activities over time can be useful for acquiring external resources. The success and speed of breakthrough innovation depend on these aspects being considered in the strategy and not having to be resolved on an ad hoc basis.

2. Articulating the target operating model

The starting point for any breakthrough project is to articulate clearly the target offer characteristics in a way that is outcome-focused, stretching (targets) and not over-constraining in terms of product details — such as target performance, key functionalities, cost, and time to market. Product architecture is a central consideration at this stage. For complex products or systems, reduction of interface complexity is a key criterion, especially when Agile approaches need to be introduced. Early attention must also be given to market access.

3. Articulating a scientific approach to innovation

However, achieving true breakthroughs requires not only degrees of freedom, but also a strictly scientific approach to test and validate ideas, features, and so on, in iterations. The higher uncertainty in breakthrough projects can be successfully countered by initiating a build-measure-learn loop. In this approach, hypotheses are formulated and an appropriate test design is developed. The actual development and experimentation take place along these orientations. By comparing test results with the hypotheses, scientific learning is achieved and further development is conducted accordingly. Therefore, even failure in experiments, market tests, and so forth, is an insightful source of learning and, from a breakthrough innovation perspective, will enable further progress.

In addition, the build-measure-learn approach forces early attention to market access as part of the process of deriving and testing hypotheses. For example, would the innovation require new channels to market and/or branding? Putting these considerations off until later stages is one common reason for the failure of promising breakthroughs to go through to scale-up and commercialization. Simply put, a scientific approach to breakthrough innovation minimizes the risk and cost of developing products, services, processes, and so on, that ultimately fail and enables continuous tracking of progress. And a persistent focus on minimizing cycle time through the build-measure-learn loop is what separates the excellent innovators from the good ones.

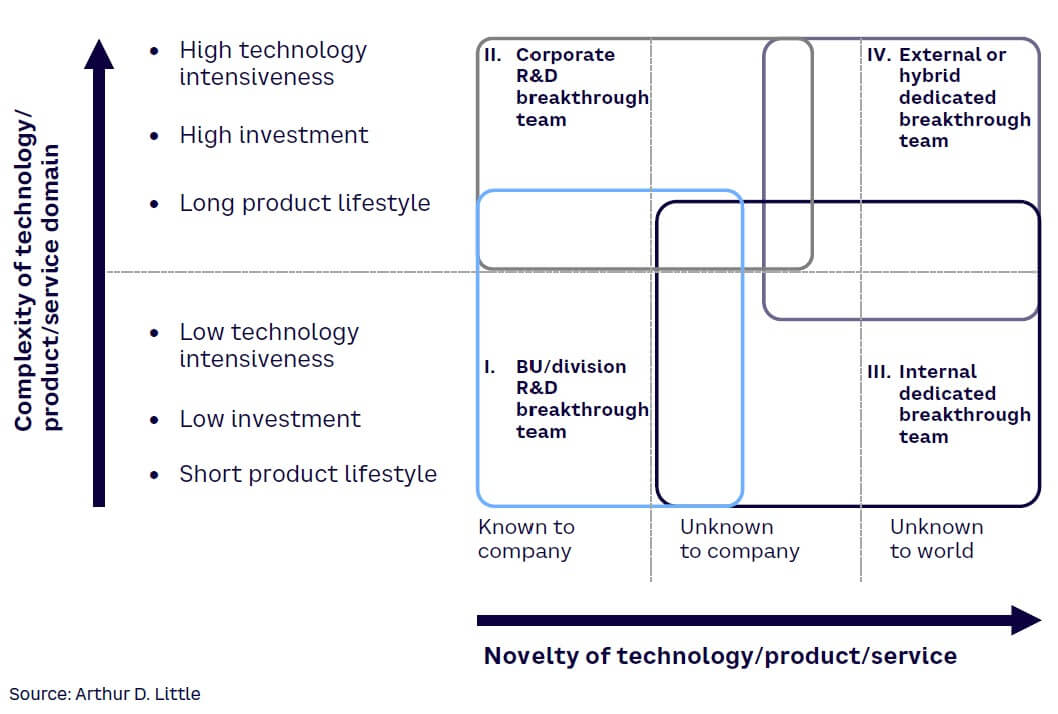

4. Choosing the right operating model

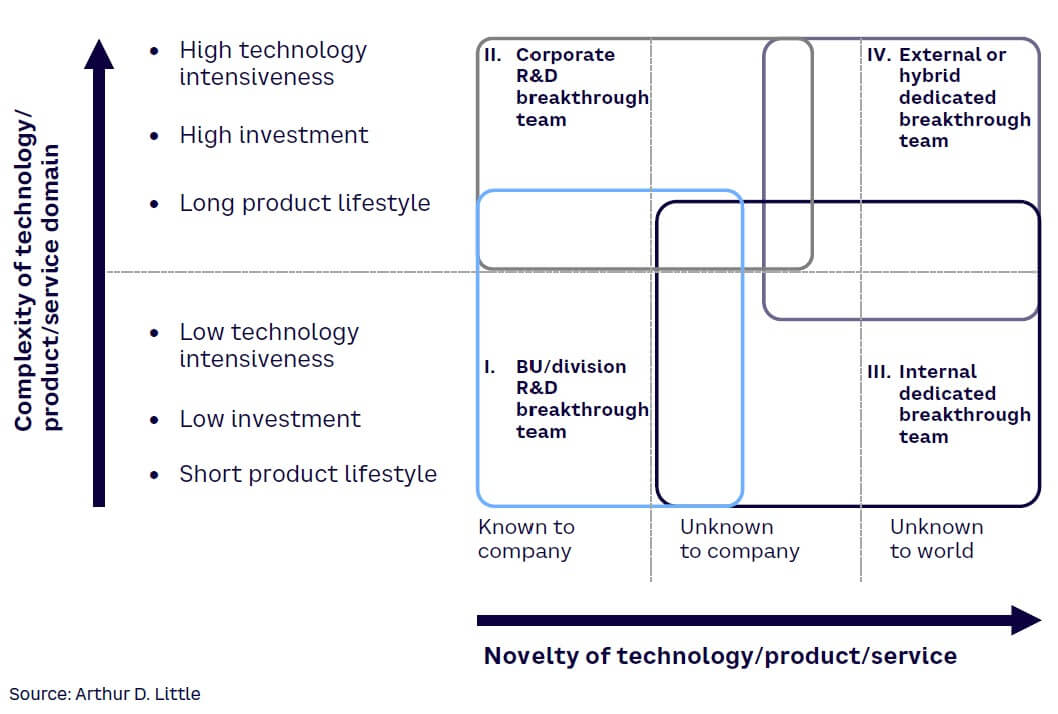

Breakthrough and incremental innovations have different requirements, levels of uncertainty, and complexity. Consequently, they require different operating structures, frameworks, skills, and mindsets to be managed in the most effective way. At a basic level this often means creating a dedicated breakthrough team (previous ADL analysis shows this approach yields 15% higher satisfaction compared to companies with no dedicated breakthrough function).[7] Results from the GIEB support this, with a strong correlation between setting explicit boundaries, expectations, and resources and breakthrough innovation success.

When creating a team, there are multiple potential operating models that can be deployed (see Figure 12). Choosing the best fit should be guided in the first instance by two dimensions:

-

The complexity and technology intensiveness of the domain (e.g., aerospace products tend to have higher complexity and investment levels than, say, food products).

-

The novelty of the technology, product, or service being developed — from “known to company” through to “unknown to the world.”

Applying this thinking identifies four generic operating models that are effective in different circumstances. Larger companies may need to use more than one model simultaneously across different areas of the business.

Business unit/division R&D breakthrough teams

If the domain is known to the company and the breakthrough sought has a relatively low level of complexity and required investment, breakthrough innovation teams can be located within the business unit (BU). However, if needs change, these teams are unlikely to be able to cope with high complexity and risk. Additionally, resources can be susceptible to short-term BU reprioritization pressures and sometimes undue BU procedural red tape (see Chapter 4).

Corporate R&D breakthrough teams

Corporate R&D breakthrough teams are better suited to more technology-intensive or higher-investment known domains where a longer-term perspective, specialist technical skills, and/or the use of unique corporate assets are required to develop the breakthrough. However, locating teams under the corporate R&D umbrella potentially introduces barriers to successful breakthrough thinking. For example, there can be an overemphasis on “technology push,” and breakthrough innovations can become misaligned with the business or be stifled by corporate control and culture. Finding a project leader with good business skills as well as technical expertise is key.

Internal dedicated breakthrough teams

Internal teams are separate from corporate R&D and report directly to technical or business R&D top management. Teams are multifunctional and have the freedom to operate outside core product development procedures and controls. While they may be more effective in innovating in areas of greater uncertainty, they require strong senior governance to ensure that the team’s independence and integrity are maintained in the face of short-term corporate pressures, as well as to ensure that the team does not become disconnected from the business but delivers sufficient short-term value to justify the ongoing investment.

External or hybrid dedicated breakthrough teams

In the case of “grand challenge”–led radical or game-changing innovations that push the boundaries of science, it is often necessary to use external expertise not available inside the company. The team could be hybrid internal/external or even almost entirely external. In addition, hybrid teams can be strengthened through strategic alliances with other firms, which can be particularly beneficial later on in terms of market access through new channels and/or branding. The team could be created as a separate legal entity or kept within the current legal framework, depending on issues such as the scale of likely investment needs and the fit with corporate strategy. In the case of technologically complex innovations with high uncertainty that are well outside core business, models such as ADL’s “Breakthrough Factory” may be used. In this model, world-class external expertise is identified and recruited under time-limited contracts, led by a senior project or program leader with deep technical or scientific knowledge as well as entrepreneurial capabilities. Using time limitations means that the best individuals can be hired on merit, even if they don’t fit the typical corporate profile. Google’s Advanced Technology and Projects (ATAP) and the US Defense Advanced Research Programs Agency (DARPA) are based on similar structures.

Regardless of the model chosen, any breakthrough innovation project is strategic and should involve management at the corporate level. Managers should also pay attention to key questions around management of scarce resources (that cannot be dedicated) and whether or not to create a legal entity for the project.

5. Build a cross-functional approach

Breakthrough innovation requires a range of skills and “buy-in” from many different parts of the organization. Companies must therefore involve functions beyond R&D, including manufacturing, marketing, procurement, IT, and customer insight. This must be done from program inception so that market, roadmap, product, resources, governance, and funding can be optimally designed. The most successful companies actively engage and involve cross-functional resources rather than simply having cross-functional steering groups, such that the initial inception team effectively becomes the first iteration of the team that will eventually scale up and launch the new business.

However, before staffing the team with largely cross-functional resources, there is one other key aspect that is important for success, relating to how the breakthrough project is initiated. We refer to this as the “Iteration Zero” approach. This approach involves, at the outset, setting up a multidisciplinary taskforce to identify and mitigate the main uncertainties, which are much larger than for a normal project. The key point is that the taskforce is set up to be the first iteration of the new “company” to be created, not just a concept-phase study group.

The Iteration Zero taskforce starts by clarifying aims, ambitions, and scoping, including targets for features, cost, and time to market. It then takes initial steps to articulate clearly the gap between the current status and capabilities and the desired target, as well as identifying the main uncertainties and how they will be progressively reduced. Based on the results of this work, it is then possible for the leadership to gain a much more realistic picture of the business goals of the project, the necessary resources and funding, especially for the resource-intensive delivery phase, and the best organization and governance to ensure success.

Ring-fence funding

Breakthrough projects and programs normally (but not exclusively) require longer time frames than incremental innovation. There is therefore a major risk that budgets and resources will be threatened by short-term changes. Programs must therefore be ring-fenced to enable stable, long-term investment.

Ensure breakthrough leaders have the right skills

Bringing breakthrough concepts successfully to market requires leaders with strong entrepreneurial skills and mindset. (For more on best practices, see “Ecosystem management.”) Projects should be led by strong intrapreneurs — individuals with the ability to pursue a commercial vision with dedication, inspire others to join the cause, take measured risks, and protect an effort through to market, securing needed resources along the way. These leaders can either be existing staff members with the right skills and support or external hires. Leaders must be able to navigate and negotiate the interface between the breakthrough team and the group because it can be a key limiting factor.

3

BUSINESS MODEL INNOVATION — AN UNDEREXPLOITED TOOL

by Dr. James Semple, Ben Thuriaux-Alemán, Salman Ali, and Ignacio García Alves

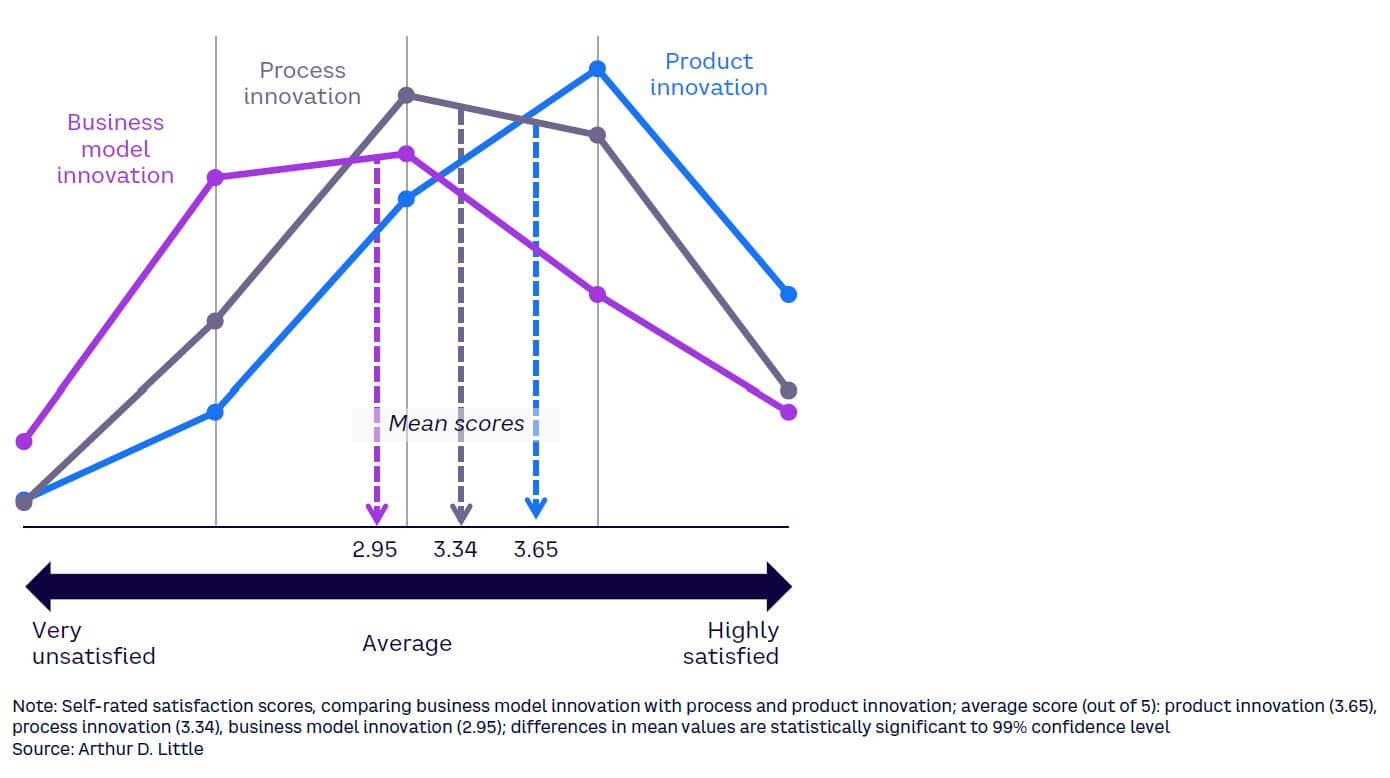

In the context of innovation, a business model used to be seen solely as a vehicle for delivering commercial value from a disruptive technology and as a tool most often employed by start-ups. (For more on business models, see “Defining business models & business model innovation.”) Today, however, strategy and innovation leaders, in businesses of all sizes, realize that they can drive sustained profitability by innovating around the business model. This delivers both productivity (value) as well as growth opportunities.

In this context, digital capabilities can act as a strong enabler for the development of new business models, where data can be better valorized both within the organization and by combining internal and external data sets.

Achieving an adequate level of traction for effective business model innovation is often challenging. While business model innovation can occur within a single division or business unit, it often requires buy-in from multiple stakeholders from across and even beyond the organization, requiring a shared sense of purpose and high levels of coordination. Nevertheless, leading practitioners know that business model innovation can:

-

Create better product-market fit. Reengineering the business model can enhance the degree to which a given value proposition is creating value for customers, without necessarily altering the product/service itself. For example, changing price points, delivery channels, resources, and customer segmentation could all lead to lower friction for customers and higher market uptake.

-

Develop underexploited market segments. Just as with achieving better existing product-market fit, engineering the business model allows for exploitation of altogether new segments of the market. It is often necessary to update the delivery vehicle of a given value proposition for a new segment.

-

Explore the potential to embed data collection with products and services to create better user insights (e.g., new use cases or insights into how users interface/combine products and services with other solutions) to identify data valorization opportunities and potential in business models.

-

Commercialize new products. The more disruptive the new technology, the greater the need for business model innovation in order to capture (part of) the new value created and avoid killing the new business through cannibalization.

-

Business future-proofing. If businesses can disrupt themselves, they shield themselves from unexpected external developments. More than the innovations themselves, the organization that is capable of changing its business model and often its position in the value chain can respond to dramatic shifts in the market driven by geopolitical, climate, and health crises.

RESISTANCE

The new landscape makes it imperative that organizations continuously reinvigorate their business models, but ADL research suggests that few do, and even fewer do so successfully. To put it bluntly, even companies that are considered to be innovation leaders in ADL’s benchmark struggle with this — and it’s not due to a lack of resources, smart managers, lack of analytical capabilities, or market pressures to innovate.

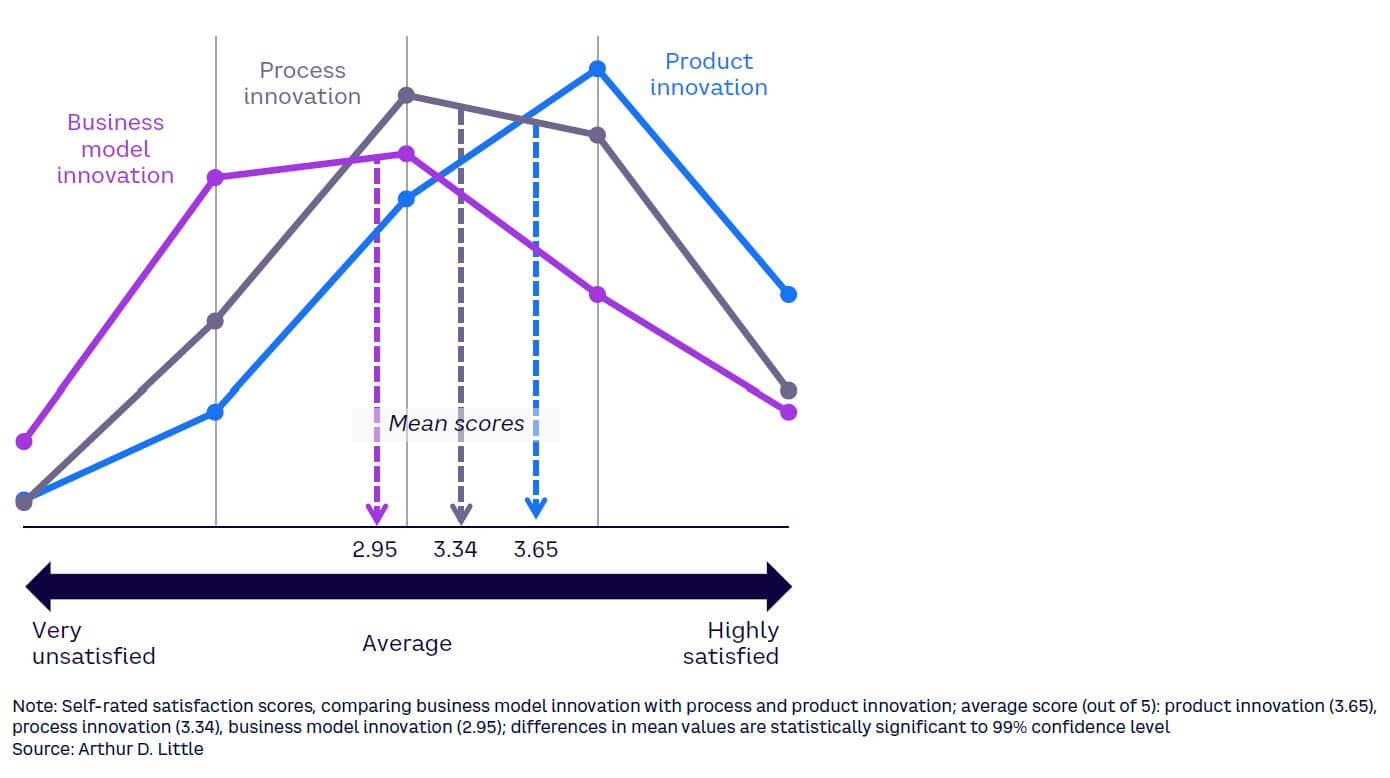

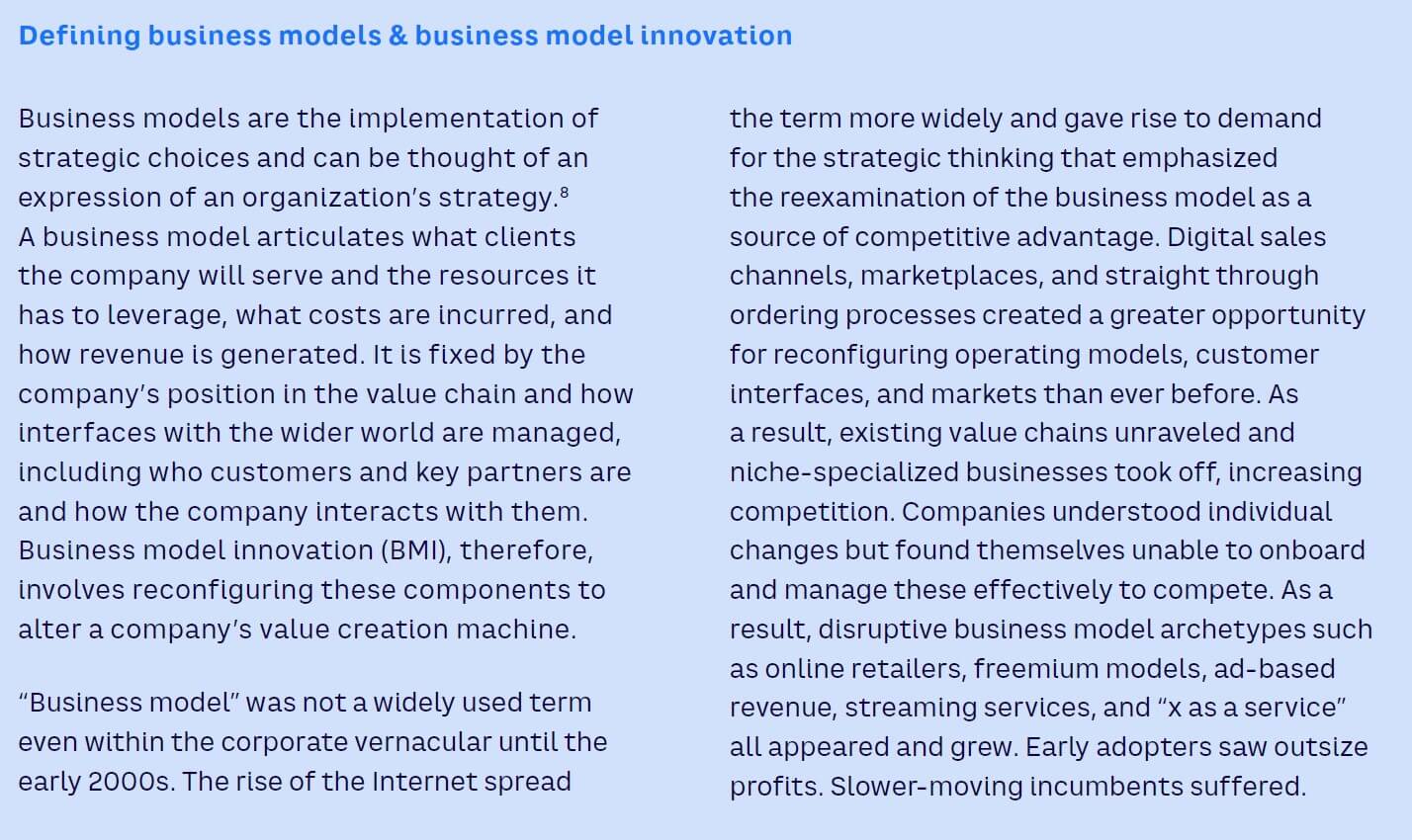

The GIEB indicates that only 60% of company leadership across industries allocate a minimum of 10% of their innovation resource to BMI. Given the benefits of engaging with this process and the risks of ignoring it, this is a surprisingly low figure. A further concern is that the majority of companies (70%) rate themselves as having average or less-than-average satisfaction with business model innovation, at visible odds with the likes of process and product innovation (see Figure 13). In ADL’s benchmarking study, the mean satisfaction rating for product innovation is 3.65/5, while the mean satisfaction rating for BMI is 2.95/5.

The question emerges: why do so many find business model innovation difficult to succeed in? The GIEB study outlines two main reasons: confusion and the change of the ongoing momentum associated with performance improvement.

Confusion

The primary challenge that many attempting business model innovation face is in coming to a collective understanding: first, what it is; second, where to start; and third, how to go about doing it (or who should be responsible). Underpinning this confusion is quite often a lack of consensus on how to explain the current company business model. There are a multitude of business model frameworks, but having a single source of truth within an organization is surprisingly rare.

Once a common understanding of the business model is defined and widely accepted, key decision makers can decide where best to start. Typically, the first decision is whether to test a new business model or tweak the existing one (see “Business model innovation breakdown”). Processes can then be put in place to begin to experiment with new business models. It’s important to manage this carefully, as there is typically quite a lot of internal resistance to business models that cannibalize the current one. It is this confusion and perceived threat to the existing business that hamper experimentation with business model innovation.

Momentum

The mechanics of innovating a business model are not straightforward, particularly for established organizations with long-standing successful product lines, customers, and industries accustomed to the products and services they provide.

Business models by their very nature are not designed to change; they typically begin by being fluid but become less agile and more resistant to change over time.

Consider the natural business model innovators: start-ups. Starting from zero, a business model has to be designed or adapted. One need look no further than Steve Blank’s definition of a start-up to see just this: “a temporary organization designed to search for a repeatable and scalable business model.”

But what happens when a young start-up gains some traction? When a young company gains a foothold in a market, the fluid business model solidifies. Emphasis shifts from experimentation of value propositions, channels, products, and resources to growth, margin, and ultimately efficiency gains and cost minimization. As time goes on, it becomes increasingly difficult to innovate at the macro level of the business model and fight against the existing momentum of the business direction.

Larger firms do not have the luxury of discovering a single new winning business model; they must focus on sustaining their existing business model(s), while replicating others. The resources and processes that work so perfectly in their original business model do so because they have been honed and optimized for delivering on the priorities of that model.

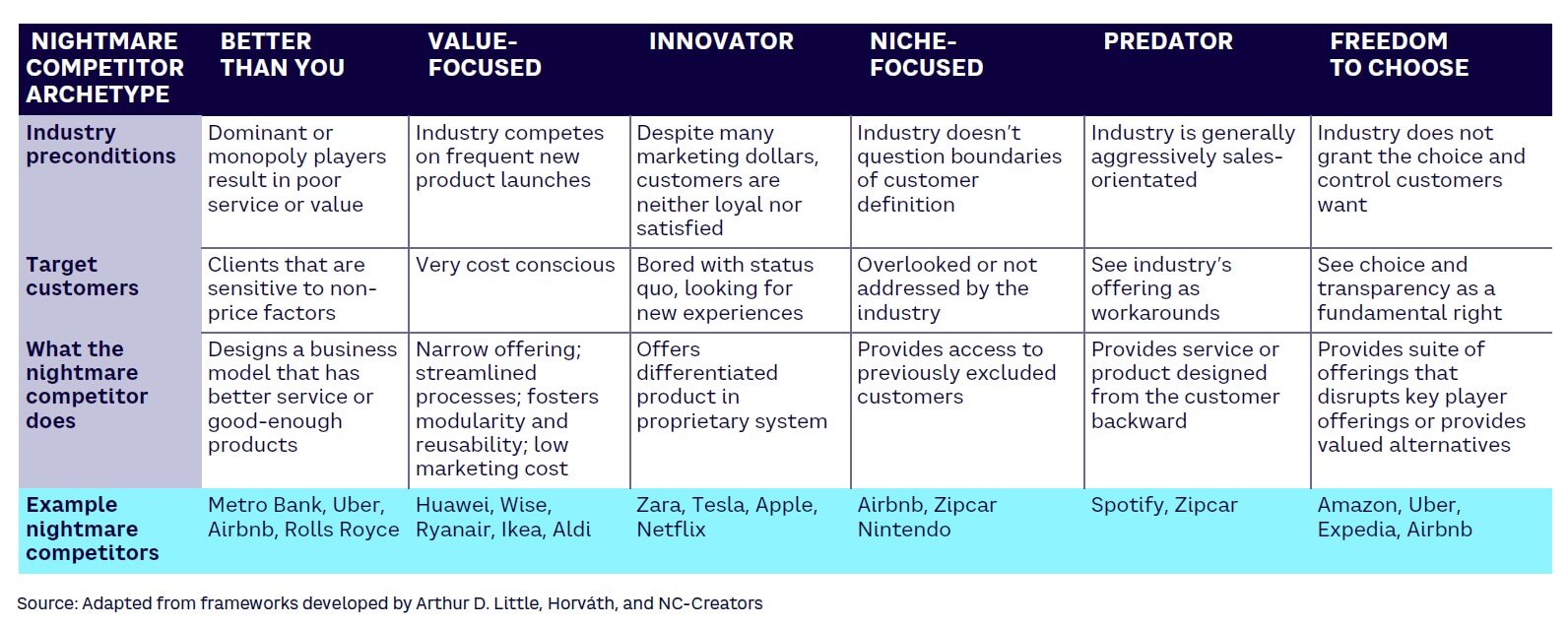

UNLOCKING CHANGE WITH THE NIGHTMARE COMPETITOR

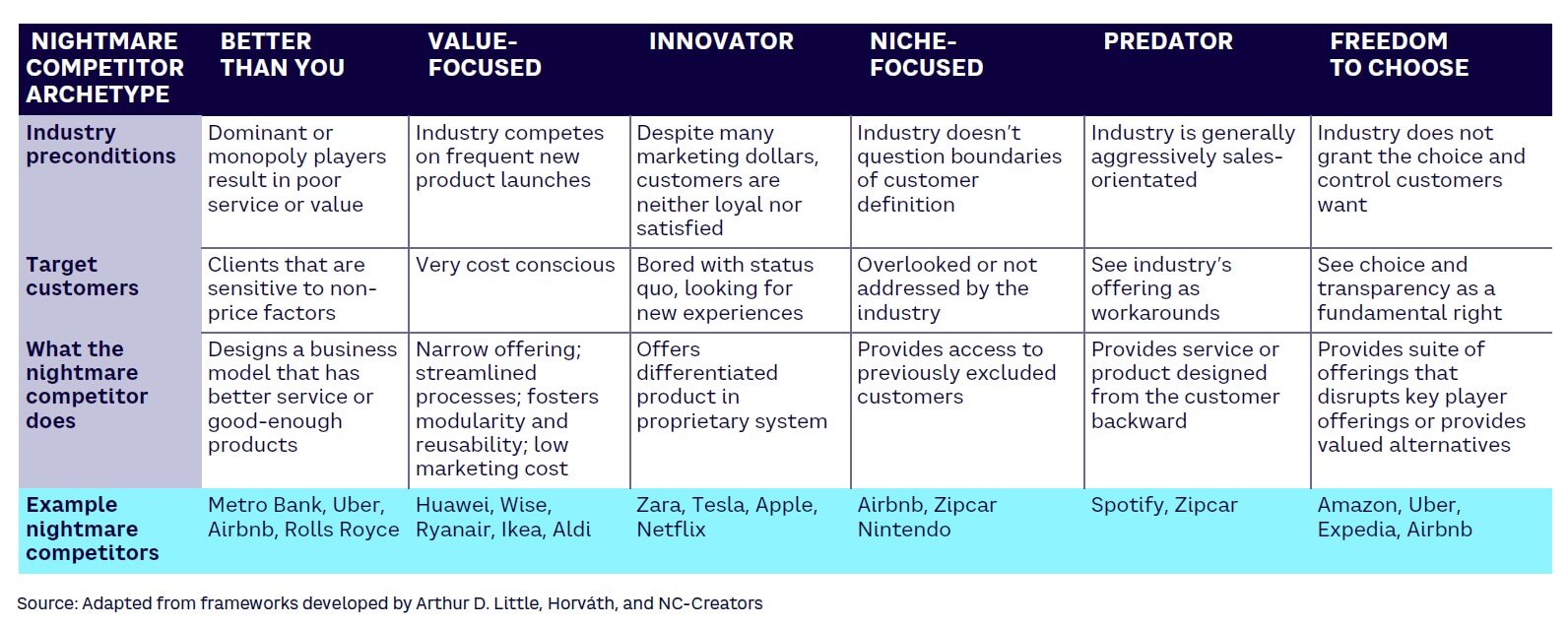

To overcome the twin challenges of confusion and momentum, a simple yet effective methodology to employ is the nightmare competitor exercise.

The nightmare competitor is the hypothetical entity that challenges your core and future growth businesses, creating business models that successfully steal away your customers. The exercise invites teams to consider what this competitor looks like for them, what attributes it would possess, and how they can either overcome it or become it.

By locating the new or altered business models outside of their actual organization, individuals are more free to imagine and ideate, bypassing common cognitive biases that blind them to the possibility of new business models, such as the status quo trap (“but things are just fine the way they are”), the sunk-cost trap (“but we have invested heavily in X”), and the overconfidence trap (“but we know our business model is

future-proof”).

In practice, selected individuals envision a disruptor of the organization in a workshop setting, defining first its positioning, purpose, and business model, and finally the key ingredients for its success. Participants then pitch back the imagined nightmare competitors, with the aim of convincing customers to buy, employees to join, investors to fund, and stakeholders at large to take notice.

Setting different workshop groups with different nightmare competitor archetypes (see Table 1) generates a comprehensive list of alternative business models.

Of critical importance is involving a diversity of voices. Companies see the best results in the nightmare competitor exercise when participant selection ignores organizational hierarchy, focusing instead on people with functional expertise in strategy, corporate foresight, operations, sales, marketing, or R&D and includes external participants from knowledge domains outside the industry, such as digital technologies and business models, potential customers, suppliers, entrepreneurs who have disrupted their markets, and lateral thinkers capable of recognizing transferable patterns and solutions.[10]

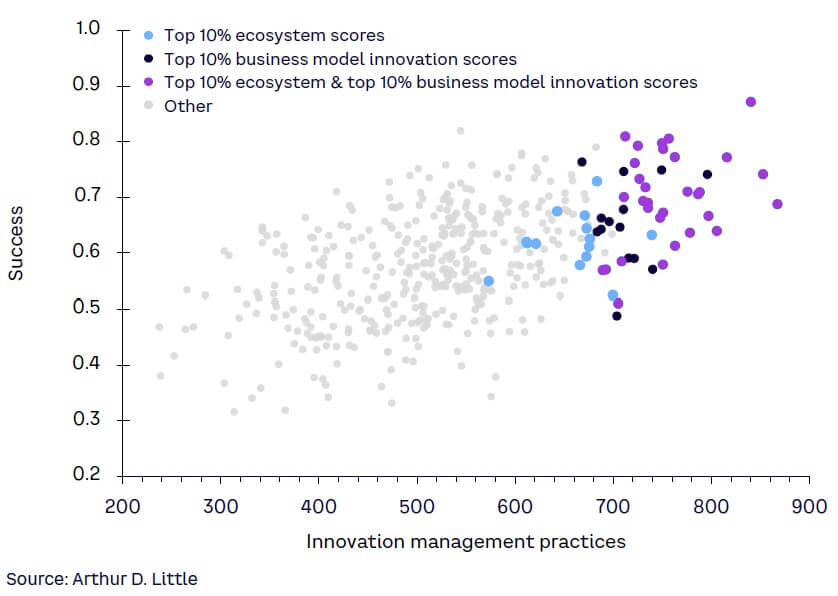

This is because underpinning both business model creation and business model alteration is one recurrent theme: how effectively an organization can innovate with ecosystem partners, from customers, to suppliers, to partners, to start-ups. Because the business model itself is intrinsically linked with partners, customers, and channels, BMI typically occurs at the interface of the company’s activities with external partners. In fact, when we look at ecosystem innovation as a core innovation management practice, we see that those companies that perform well in both business model innovation practices and ecosystem processes are the top performers in terms of innovation success (see Figure 14).

The nightmare competitor framework facilitates the building of a shared understanding of the business model and exploration of new ideas. It allocates time and resources for BMI and creates a strong culture of collaboration, all of which are critical ingredients for success.

In summary, business model innovation provides a bridge between strategy and innovation practitioners. Through collaborative design and thinking, effective business model innovation can be a driver for value and growth within any business in the 21st century. Furthermore, business model innovation is the only antidote to future failure as existing business models become superseded.

4

INNOVATING FOR VALUE BY ADDRESSING THE GAP IN BU PERFORMANCE

by Dr. Habib Hussein, Ben Thuriaux-Alemán, Elis Wilkins, Dr. James Semple, Shota Mitsuya, Rui Ibuki, and Atsuro Inoue

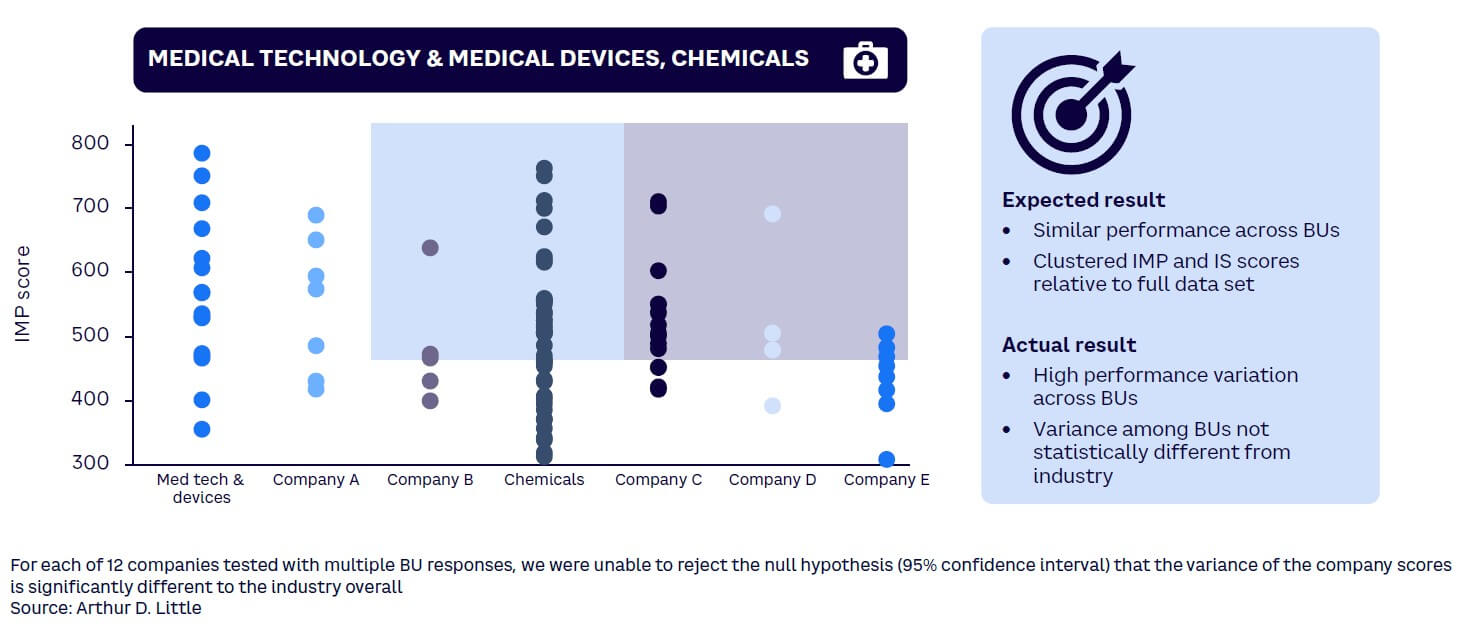

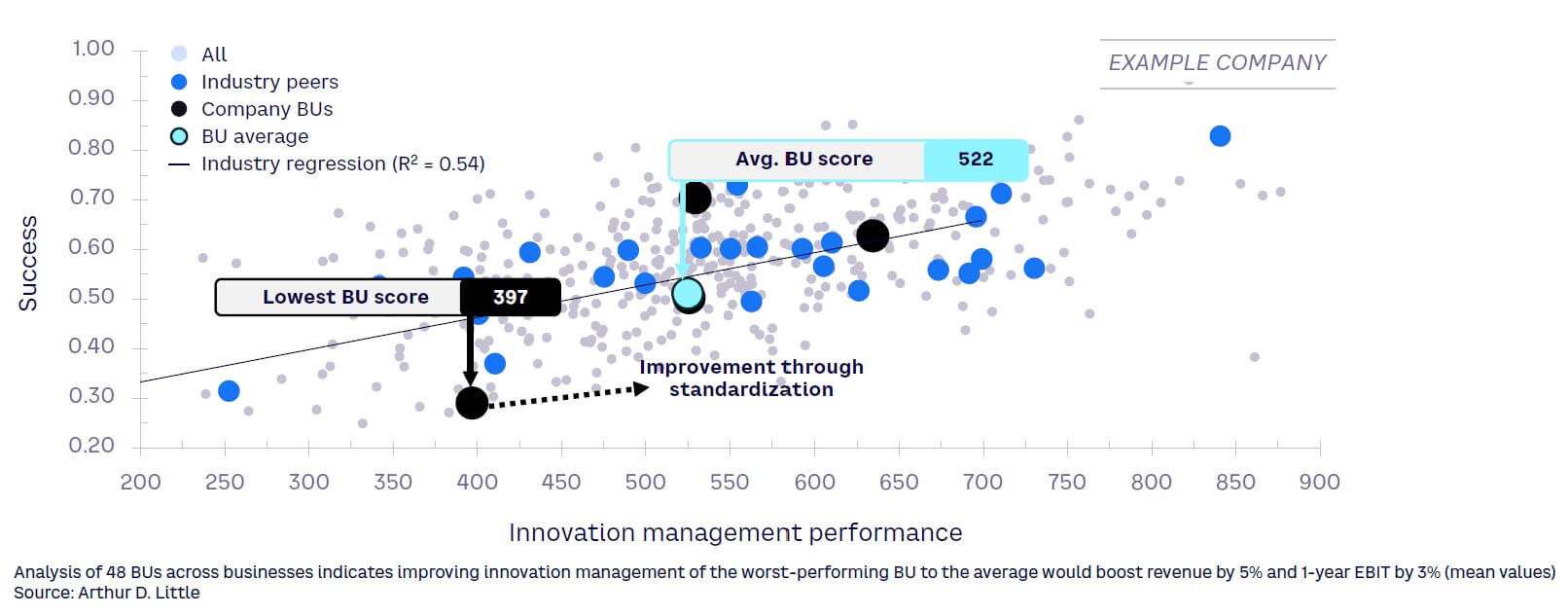

As we have discussed in this Report, alongside innovating for growth, organizations need to innovate for value. The simplest way to achieve this is to share good innovation practices across the organization. However, ADL analysis highlights wide discrepancies in innovation management practices between different BU R&D teams within the same company. This contributes to lower overall performance and represents a 5% BU revenue gap, as well as impacting EBIT and time to breakeven. This innovation management gap spans all industries and leads to underperformance with duplication of efforts, a lack of transparency over the R&D portfolio, and lower revenues.

If two factories belonging to the same organization failed to effectively share manufacturing best practices that could dramatically impact performance, the COO’s days would be numbered. Yet, despite the importance of innovation to business success, the same rule does not seem to apply when it comes to sharing innovation management best practice between different BUs.

THE INNOVATION MANAGEMENT GAP

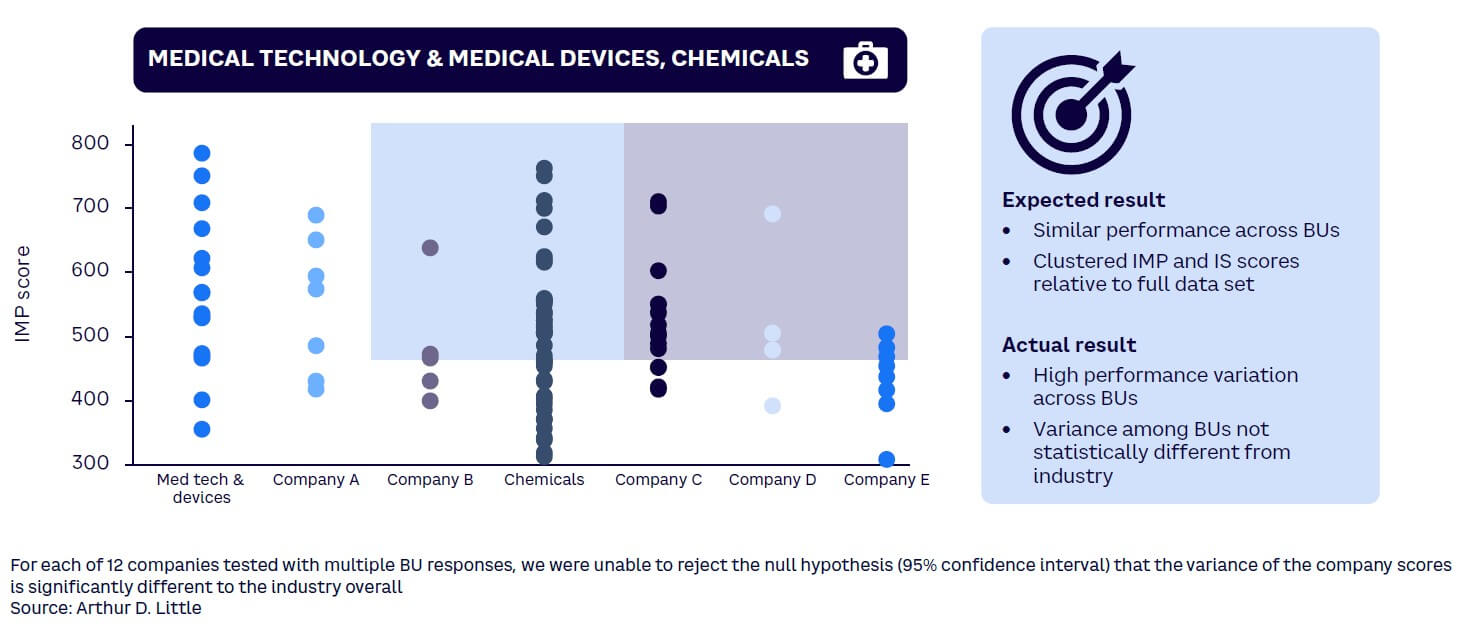

Analysis of the GIEB found wide variability between BUs within the same organization (see Figure 15). In many cases, in fact, it was impossible to tell that these BUs were part of one company, such was the performance spread. These gaps occurred across multiple industries (including automotive, telecoms, transport, manufacturing, medical devices, and chemicals). Innovation practitioners back up this finding: 78% of those surveyed said that standardizing best practices was a challenge and the failure to do so has a negative impact on innovation performance.

The impact of this gap translates into multiple issues, including:

-

Lower overall innovation performance across the organization. Significant value is being left on the table through inconsistent innovation management practices.

-

Slower time to market and a longer breakeven time.

-

No consistent view of innovation processes/projects across the firm, leading to a lack of transparency.

-

Duplication of programs and repetition of processes that have not worked in other BUs, thus reinventing failure.

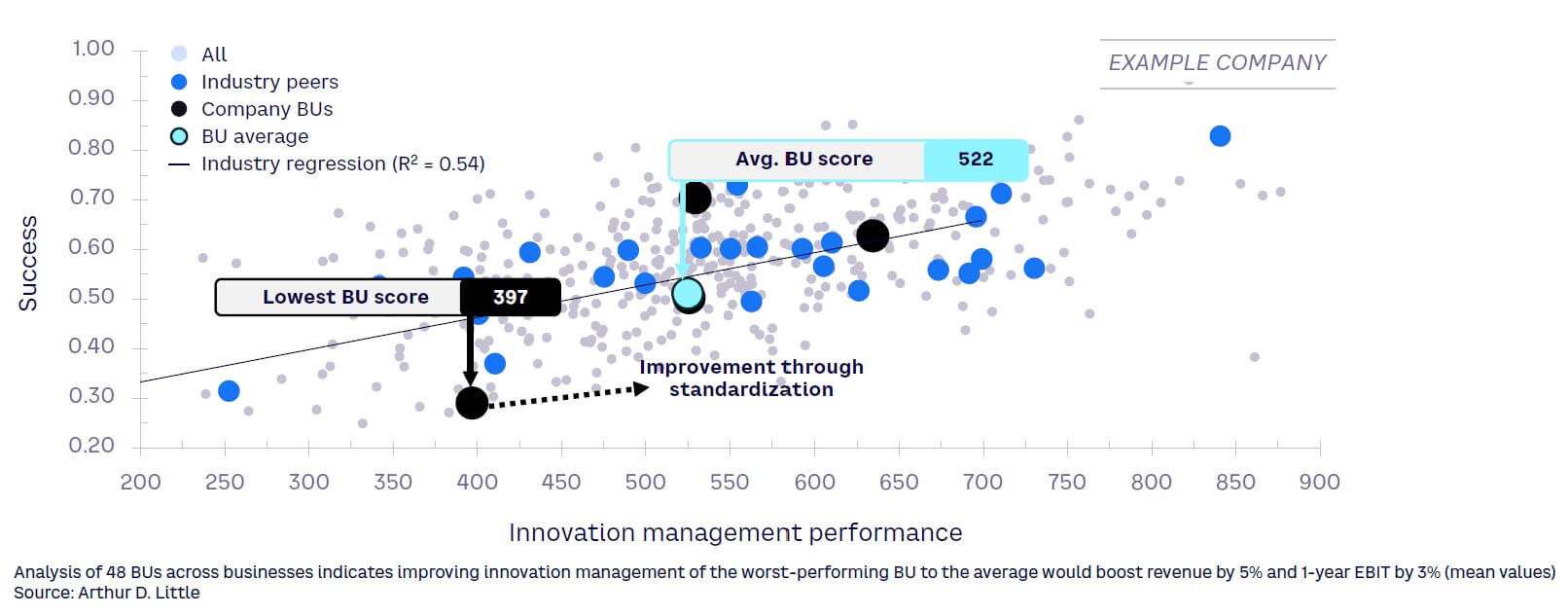

Drilling down into the data, we investigated multiple organizations across a variety of sectors, comparing performance of BUs within their industries and removing sectoral variations (see, for example, Figure 16). ADL found that the lowest-performing BUs in our sample of 48 are losing out on an average of 5% revenue (range 1%-15%) due to their subpar innovation management practices. They could further see a 3% point EBIT boost (range 1%-6.5%) and reduction in time to breakeven by bringing their innovation management practices up to the cross-BU average. Further improvements could also be targeted by aiming for top-quartile performance or by looking for inspiration with the top 10% of peer-group companies.

UNDERSTANDING THE ROOT CAUSES

A combination of client experience, academic research, and an innovation management workshop that brought together more than 50 industry innovation leaders and senior academics identifies three groups of root causes:

1. Leadership & incentives

Carrying out R&D in BUs strengthens the relevance and applicability of innovation. However, it also leads to a focus on the BUs’ own, incremental, and often short-term innovation goals, particularly if they are incentivized to hit quarterly revenue targets.

This risk-averse mindset can lead to an unwillingness to adopt new ideas and practices as leaders fail to see the potential benefits. The lack of an organization-wide governance strategy for innovation management or senior management support for an overall innovation focus holds back efforts to collaborate and share best practice. Often, senior innovation executives in the central team (such as the CTO), focus on developing technologies in areas beyond BUs, and lack a perspective on how to share best practice across BUs.

2. Organizational structure

BUs want autonomy over innovation and may see organizational best practices as inappropriate for their needs, targets, and aims. There may also be variances in innovation clock cycles (i.e., the pace of innovation) and maturity levels between BUs, particularly if they are located in multiple geographies or have different heritages, such as being added by acquisition. This all contributes to a rejection of organizational best practices, no flow of ideas between BUs, and a lack of collaboration between teams. This not only harms innovation efforts in BUs, but holds back cross-BU collaboration around innovation, preventing the creation of new convergence products and services.

3. Business unit culture

Individual business units have built up their own cultures and may even compete against other parts of the same organization, undermining efforts to increase transparency and the sharing of best practice. Conflicts around power, politics, and resources lead to an insular “not invented here” mentality and a strong resistance to external “interference” in BU innovation management. Central management and centers of excellence are seen as out of touch with BU needs, leading to a lack of engagement. In many cases, sharing and collaboration is viewed by BUs as either a potential weakness or an unwelcome distraction from achieving their specific goals. These cultural differences further manifest themselves in a wide variance in how innovation is described and valued — there is no shared language of innovation across the organization. This makes it particularly hard to create common forums and spaces for collaboration.

ADDRESSING THE CHALLENGE

These challenges can be overcome but require a strategic approach, with senior management backing:

1. Leadership & incentives

Senior management must first understand the size of this innovation gap and then take an active role in closing it, emphasizing the strategic importance of innovation management best practice to the entire organization. They must help make it part of overall company culture. It is vital to build trust with BUs, demonstrating that adopting best practices is an opportunity not a threat. This can include incentives, such as providing access to additional innovation funding for BUs that deploy best practices and meet innovation targets.

Senior leadership then must create a balanced cross-BU (XBU) innovation portfolio with clear plans and protected budgets for short-, medium-, and long-term innovation targets. This can also include areas for convergence between BUs. Chemicals company Johnson Matthey has one “single source of truth” company-wide innovation portfolio to monitor and control innovation and allocate resources. This features a standardized approach to innovation management based on best practice, while allowing some variability for different BUs.

An alternative approach, as practiced by Japanese glassmaker AGC, is to focus and invest heavily on innovation/business portfolio enhancement and take a more aggressive role in managing conflict between the central innovation organization and the BUs. This may lead to complaints from BUs, but in this case led to significant innovation success.

Management should set clear expectations for innovation portfolio transparency including dashboards with board-level monitoring and KPIs. As an example, materials technology provider Umicore has an Innovation Excellence Board.

2. Organizational structure & culture

Start by establishing a common language to describe innovation and set the vision and mission for the organization, while understanding that there may be variations between markets based on BU maturity and local needs.

Engage BUs in the change process, creating a flexible innovation management framework containing guidelines, agile processes, and common practices that can be adapted to specific local needs while providing the rigor and transparency needed by the head office. For example, utility company Engie is investing time in aligning/coordinating innovation practices between BUs. Additionally, increase collaboration by encouraging the movement of people and, in turn, ideas. At a more radical level, changing the structure of the organization to encourage innovation excellence can be an option. For example, in the chemical industry, the traditional split between product teams and functions (such as process engineering) can be transformed to align with customer/society needs or delivering new value.

3. BU culture

Change carries risk. To minimize the potential for rejection, BU stakeholders should be engaged, involved, and listened to, creating a sense of ownership around “new” best practices.

Recruit successful and influential innovation project leaders as evangelists to demonstrate the value of best practices (from outside the organization or from other BUs). Break down silos and enable the cross-pollination of ideas through meetups, communities, and other knowledge-sharing forums. Johnson Matthey has seen real value in formalizing cross-business unit and cross-functional teams to share learnings and agree on the best ways to balance what is standardized and what is not. Champion inclusivity to involve everyone and recognize success through cross-company awards.

Introduce the right incentives and KPIs for individuals to encourage the sharing and adoption of best practice. Encourage (healthy) competition between BUs around innovation excellence.

CAPTURING VALUE

An inability to share innovation management best practices across BUs is holding back innovation success for many multi-BU organizations. This impacts individual BUs and reduces opportunities for XBU collaboration to create converged products and services.

This gap is recognized by the majority of innovation practitioners, and while the root causes are complex, they can be overcome. Success requires senior management involvement and an approach that builds trust while ensuring harmonization, focusing on changing culture and aligning incentives.

Bridging the gap between BUs ensures organizations with decentralized R&D can successfully innovate for value, unlocking greater success across the entire company.

5

THE BENEFITS & PITFALLS OF AGILE INNOVATION

by Dr. Habib Hussein, Philip van Basten Batenburg, and Dr. Arnaud Siraudin

Selectively applying the Agile methodology is proven to increase innovation success. It enables teams to identify bigger ideas, develop them faster, and execute them better and more efficiently through a relentless focus on the customer or end user.

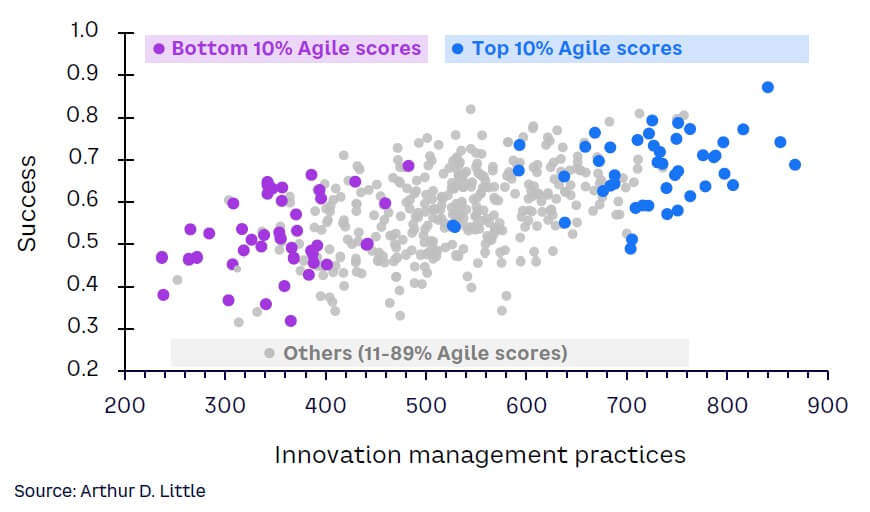

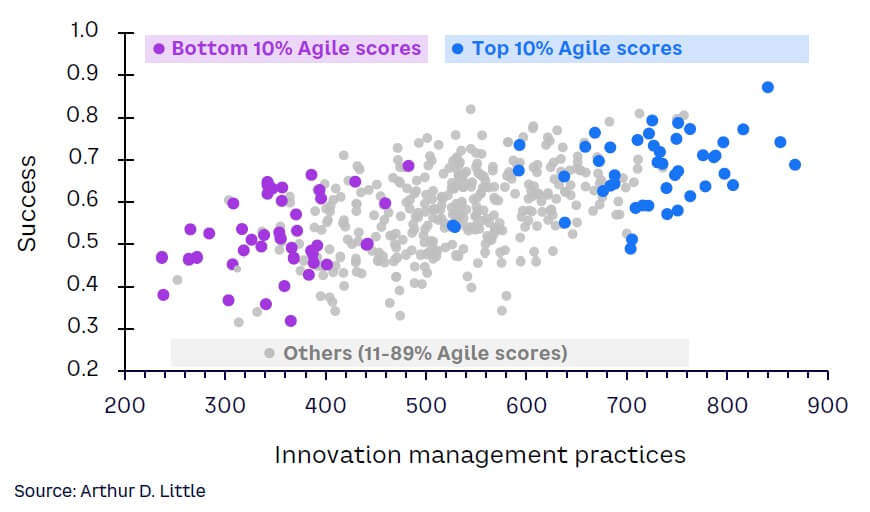

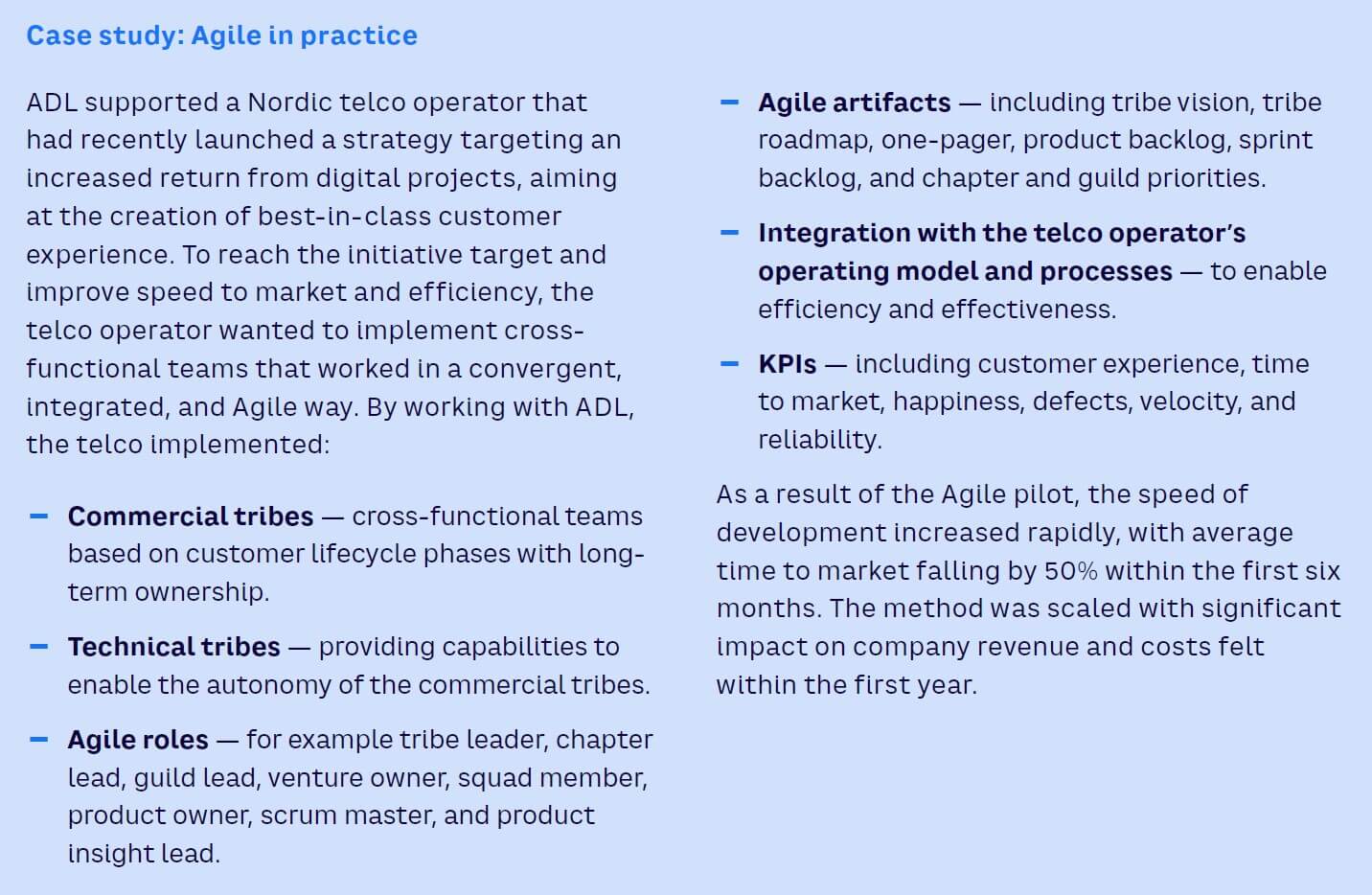

The GIEB data demonstrates a relationship between Agile performance and innovation success (see Figure 17). Those organizations/BUs that score highest for the use of Agile methods also generally demonstrate higher innovation management practice scores, showing that Agile is well-integrated into their suite of innovation methods.

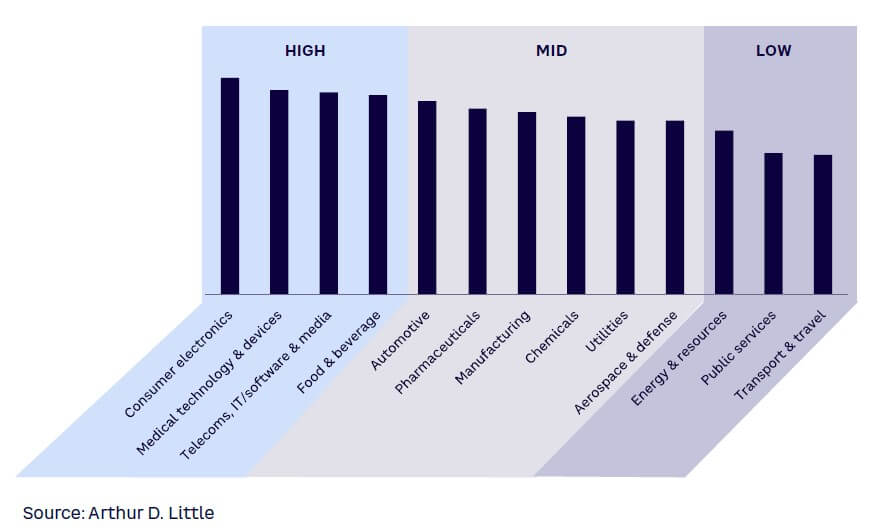

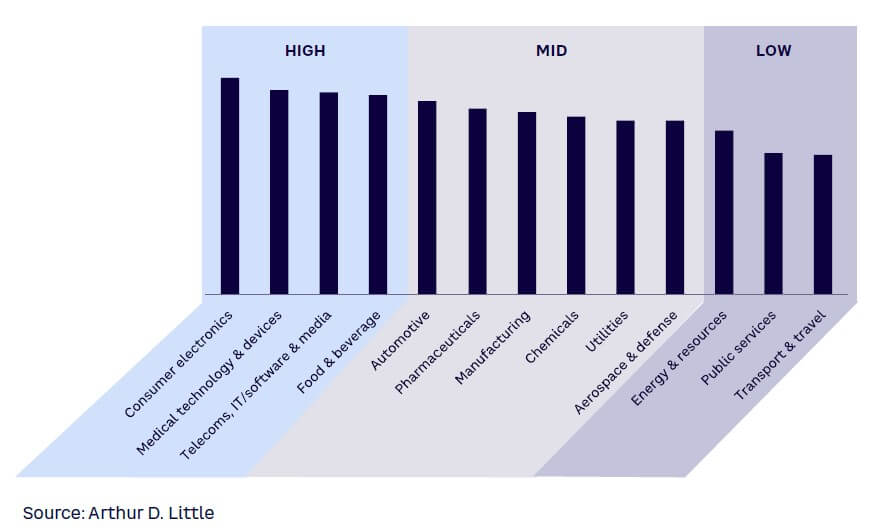

Agile innovation streamlines innovation processes and reduces oversight. This enables autonomous innovation teams to iterate rapidly, testing innovations, concepts, and hypotheses with customers to deliver overall faster innovation. From its original use in software development, it has spread to other sectors, notably consumer electronics, telecommunications, information technology, media and electronics, and food and beverage. There is significant variation between industries however, as the advantages of Agile depend on their specific requirements for innovation (see Figure 18). Capital-intensive industries, the public sector, and healthcare and pharmaceutical industries have tended to lag in terms of Agile innovation adoption while consumer electronics, telecoms and media, food and beverage, and medical technology/devices have seen relatively good take-up of Agile innovation management practices. That said, even in pharmaceuticals, the range of biotech start-ups has created a very dynamic environment. While it takes time to develop a new drug, the speed with which the COVID vaccines were developed showed what Agile approaches can achieve when there is sufficient pressure and the willingness to balance the risk of inaction versus the additional risks of rapid development.

How can Agile be applied to innovation management?

When applying the Agile approach to innovation, the key principles remain the same as for software development. However, certain elements require a different focus:

-

Iterative approach. The heart of the Agile approach in innovation is the use of a series of rapid (two-to-four-week), iterative loops, similar to an Agile iteration for software. This helps address uncertainties and unknowns, test prototypes and concepts, and then drive the development of parts of the overall solution. It avoids tunnel effects and pushes teams to deliver intermediate products, increase know-how, and accelerate the pace of development.

-

Teams. Within the innovation environment, Agile teams are multidisciplinary groups of specialists that expand and contract depending on the current project focus. For example, if a team is testing a business model or other concept, there might need to be greater involvement of internal or external people with experience and knowledge in finance, sales, and behavioral economics.

-

Governance. While governance is not often identified as a key element of Agile software development, it is critical within product development. In the Agile environment, governance acts less like a go/no-go decision maker and more like a coach to project teams, with added responsibilities for managing tradeoffs in feature selection and resource sizing. Governance makes sure the customer’s voice is heard and helps teams to navigate organizational challenges.

AGILE IS NOT THE SILVER BULLET FOR INNOVATION SUCCESS

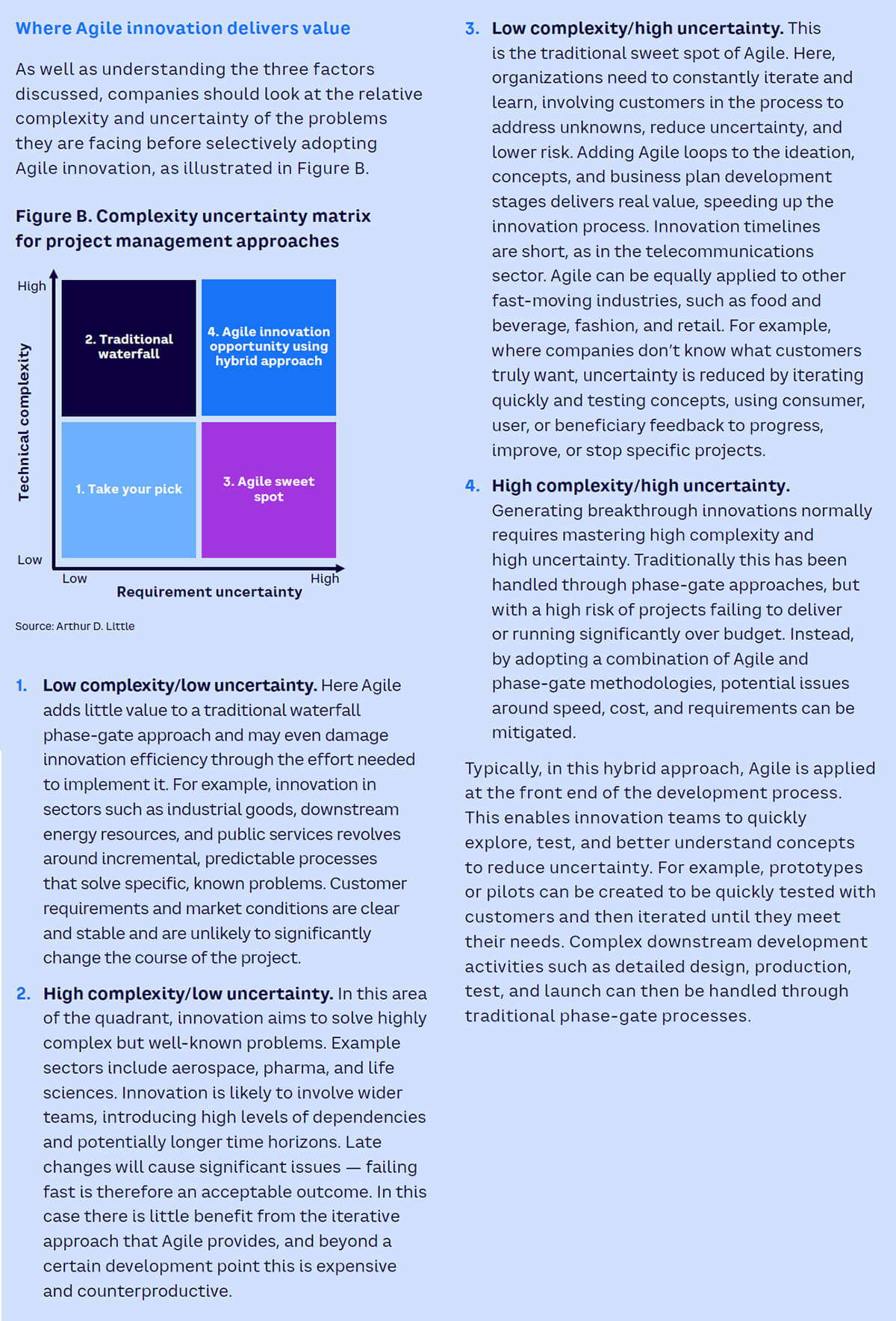

Based on these findings, it might seem logical to recommend Agile to every organization looking to improve its innovation success, and to abandon traditional phase-gate (waterfall) processes. However, the Agile and phase-gate approaches are distinct in their implementation and generally suited to different innovation objectives when applied outside software (see “Where Agile innovation delivers value”). Agile is therefore not a silver bullet that will magically solve all innovation project challenges. When deciding whether to apply it, companies should consider three factors:

-

Scope variability. Agile works best in areas where work is carried out within complete teams that have the resources, skills, and capabilities to act autonomously, without any external dependencies, or where there are limited interdependencies. This is a fundamental difference between Agile and other ways of working. It can be difficult to implement in R&D, where activities are typically interdependent and based on discrete technical requirements difficult to separate. In the same spirit, a project with no uncertainty and a complex development process that needs to be delivered quickly can be more efficient with a V-cycle than an Agile approach.

-

Time horizons. Software development projects, especially Web-based services, work to short, constrained timescales, with delivery sometimes expected within months or even weeks. Agile methods meet this need through quick learning loops that enable rapid, iterative development. In contrast, ADL’s research shows that half of all major industrial innovations take five years or more to generate first revenues, and even breakthrough success stories sometimes take a very long time. Balancing these two, radically different time horizons is particularly challenging for many innovations or industries.

-

Risk exposure. Agile working is based on speed, with a mantra of “fail fast and fail cheap.” Again, while this may fit strongly with activities such as software development, it is often not possible in the context of many industrial R&D activities. Unlike developing software, innovation is not a smooth process where small incremental development steps can be taken and discrete components of the final deliverable developed in isolation. It often requires major steps in terms of commitments, whether in substantially increased investment or market exposure. Uncertainty is not always something that can be measured and managed, due to a high number of dependencies and levels of complexity. Failing fast or cheap may simply not be an option.

CHOOSING THE RIGHT PROCESS TO USE

Evidence from the GIEB indicates that Agile can speed up the innovation process if it is implemented in the right way for the right opportunities. However, innovators should not expect it to be the best approach for every project. A portfolio assessment is needed to select the right innovation process (Agile, phase-gate, or hybrid) based on the needs of the specific project, industry, and region.

Asking these questions can help understand when Agile will work best:

-

Market environment. Do customer preferences and solution options change frequently or are they stable and predictable?

-

Customer involvement. Is close customer collaboration needed/feasible or are requirements clear from the outset?

-

Innovation type. Is the innovation problem complex and solutions unknown or is the innovation incremental and based on detailed specifications?

-

Modularity of work. Will an iterative approach deliver products that customers can use and benefit from, or does the project need to be completed in full before it can be provided?

Projects that meet the first criteria for each of these questions should look to Agile innovation management methodologies, while more incremental opportunities with clear requirements or specifications will gain greater value from remaining with a phase-gate/waterfall approach.

3 RULES FOR SUCCESSFULLY IMPLEMENTING AGILE

Adopting Agile is not rocket science. However, for many large organizations successfully implementing it can be difficult as Agile challenges traditional organizational norms and hierarchies. In an Agile world, senior management are facilitators, not decision makers. This shift means they must trust and empower their teams to drive success. Following these three rules maximizes the chances of success:

-

Start small. Many organizations looking to improve innovation speed and quality embark on large-scale transformations to switch to Agile. However, this can meet internal resistance from those used to traditional hierarchies. Instead, starting small and piloting Agile with the right team on the right project is more likely to provide the quick wins the business is looking for, creating evangelists and then delivering long-term success.

-

Start simple. It is important when starting out on the Agile journey that leadership teams commit to doing “vanilla” Agile well before modifying or customizing it for their organization. Use the standard approach that has delivered success in thousands of companies. Create independent, autonomous teams, with clearly defined and fixed roles for the duration of the project, supported by all standard processes. Hiring an experienced external Agile innovation coach to mentor and support Agile pilots is also a valuable investment that executives should consider if they are serious about adoption.

-

Start with a pilot. Agile requires a multidisciplinary, self-organizing, and self-managed team that is comfortable working in changing environments with high levels of uncertainty. This is uncomfortable for many people in large organizations, including leadership. Therefore, building Agile pilots around motivated individuals is a key success factor. Creating a mindset that understands that not every project will succeed, but can be learned from, is critical to getting Agile right.

By following these rules organizations can set themselves up for success by making Agile adoption much less painful. This consequently improves innovation performance and delivers high-value products faster.

6

EXCELLENCE IN INNOVATION LEADERSHIP — PULLING IT ALL TOGETHER

by Dr. Albert Meige and Rick Eagar

As we have seen, the GIEB focuses on excellence in how innovation is managed and what is being achieved in terms of business value. However, like any other aspect of business, the capabilities and behaviors of the human being leading the innovation effort also have a huge impact on its effectiveness.

At the most basic level, innovation leadership is no different than any other form of business leadership, in that it requires a combination of strategic thinking, strong communication skills, problem-solving abilities, emotional intelligence, and integrity. Beyond this, the nature of innovation management today places a premium on other particular capabilities and ways of behaving that not all leaders naturally possess. To understand these, it is helpful first to consider how much innovation has changed over the years.

HOW INNOVATION HAS CHANGED

For much of the 20th century, business innovation was largely the domain of specialist researchers and developers in academic institutions and in the R&D departments of large corporations. Successful innovation leaders were those who were best at “fishing in their own think tank,” building unique in-house capabilities and avoiding sharing with others unless it was absolutely necessary. In the latter decades of the 20th century as industrial systems and products became more complex, innovation leaders realized the need for collaboration with others to speed up time to market, enrich creative thinking, and enable greater in-house focus on key differentiating know-how. This gave rise to the need for different types of innovation resources with broader expertise, to complement the deep-knowledge experts working in their silos.

Today, innovation has moved even further: knowledge has become highly decentralized as networks have grown, and businesses have realized that it is usually cheaper and faster to acquire most of the knowledge they need from outside. As the speed of business cycles has increased and technologies and industries have converged, capabilities to scout and organize knowledge effectively, and to quickly move from one domain to another, are now more critical than ever.

KEY CAPABILITIES FOR TODAY’S INNOVATION LEADERS

To meet these new needs, innovation leaders need to focus on five key capabilities:

-

Vision belief. While all leaders need to have a clear sense of where they are heading, strong innovation leadership requires something more than this. Innovation leaders need to have at least one stretching, challenging, and inspiring vision — a “moonshot” or “grand challenge” that they can communicate with their teams and the outside world. Not only this, they also need to believe strongly, or at least convince others that they believe strongly, that it can actually be achieved. As Steve Jobs said, “The people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world are the ones who do.”

-

Meta knowledge. Today’s innovation leader needs to be comfortable working across multiple technical domains, not just the core technology areas of the business. The leader needs to be at the center of a knowledge hub around which the innovation effort revolves, in some ways acting as a modern “renaissance man/woman.” This means that meta knowledge — knowledge about where knowledge resides, how it is accessed, and what is important/less important — is a key capability.

-

Network skills. Since innovation today happens in networks, innovation leaders need to have excellent network skills. This means more than just “networking,” in the commonly understood sense of developing relationships with multiple players, although this is also important. It also means understanding how to manage large and often rapidly changing networks with perhaps hundreds of players. Key capabilities include: the ability to shape and motivate the network, and the company’s place within it, to create the most value; the ability to spot promising collaboration opportunities in unlikely places; establishing leading-edge data analytics and knowledge-sharing approaches; and putting in place the right techniques to engage and attract diverse partners, with clear intellectual property frameworks that encourage win-win.

-

Perspective originality. It’s pretty obvious that creativity is an essential attribute of effective innovation. But not all individuals in an innovation team need to be “creatives,” and indeed as we have shown in the GIEB, the best innovation teams have a mix of capabilities including entrepreneurs, project deliverers, and others. Innovation leaders don’t necessarily need to be creatives themselves, but they do need at least to develop the key capability to stand back from a problem, think in the abstract, and adopt a different or fresh perspective. There are a range of tactics to help leaders do this,[11] such as drawing on analogies with different fields, asking “what-if” questions, purposely adopting someone else’s point of view, and applying substitution or subtraction tactics to the problem.

-

Digital first. By now, digitalization is ubiquitous and effective innovation is impossible without digital being at its core. This is not just in terms of products and services but also processes, approaches, and ways of working. Innovation leaders need to fully embrace the potential of digitalization and the rapidly evolving technologies that go with it. The Industrial Metaverse, in which businesses will be managed through connected end-to-end digital twins, is not yet with us, but aspects of it already exist. Ultimately, it will transform not only innovation management but also business management as a whole.

BENCHMARK YOUR INNOVATION PERFORMANCE

If you are curious about your innovation performance, the opportunity exists to participate in ADL’s Global Innovation Excellence Benchmark. The toolkit used for benchmarking and for this Report remains available to all firms interested in exploring innovation performance. This will give you the unique opportunity to position the innovation performance of each of your different BUs relative to their specific peers.

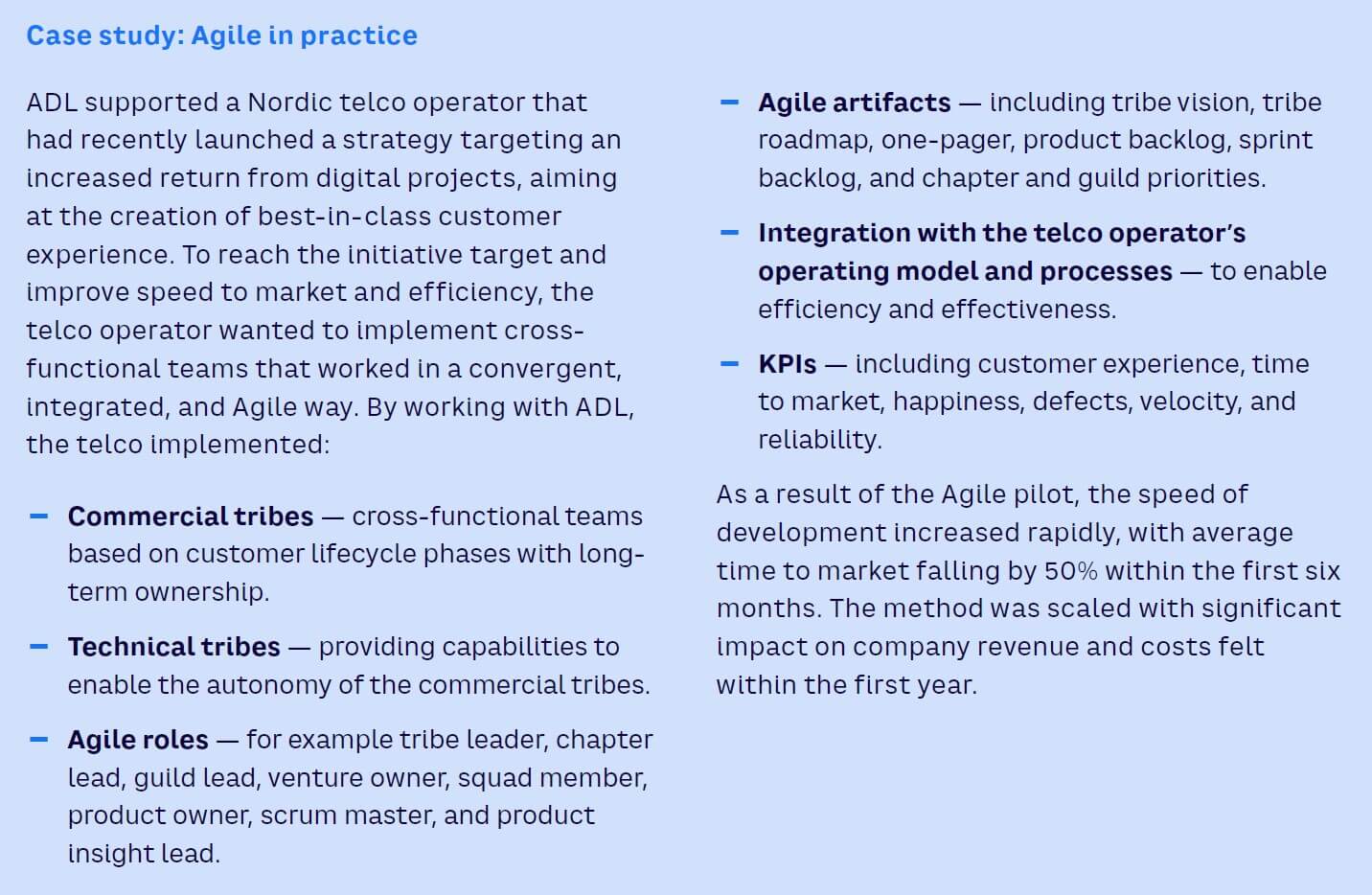

A typical innovation benchmark report provides around 25 pages of benchmark information against industry competitors. Examples of the tailored feedback reporting for an organization in the chemicals peer group (including specialty and petrochemicals) are shown in Figure 19. The toolkit can be accessed at www.adlittle.com/innovex.

ADL provides high-level diagnostic feedback based on an online assessment free of charge, but often more complex analysis is needed to compare the performance of multiple business units or to carry out deep dives on the specific issues or to generate industry-specific case studies of best practices.

IN THE WORDS OF THE ACADEMIC & BUSINESS COMMUNTIES …

“The 9th edition of ADL’s Global Innovation Excellence Benchmark (GIEB) survey identifies the complex but significant relationships between different innovation management practices and innovation, market, and financial outcomes. It combines a focus on five fundamental components of innovation, from breakthrough to business models, with a deep analysis of how the effectiveness of different innovation management practices varies by industry sector. These insights provide clear recipes and pathways for organizations of all types to improve their innovation management processes, practices, and outcomes.”

Prof. Joe Tidd

Professor, Technology & Innovation Management, Science Policy Research Unit,

University of Sussex, England

“ADL’s GIEB Report is a very insightful document. It not only highlights improvement opportunities in the way we innovate but also provides clear, specific directions and ideas on how to best address these opportunities.”

Dr. Nicolas Cudré-Mauroux

Group General Manager,

Research & Innovation (CTO),

Solvay

“Great read with thought-provoking evidence underlining the importance of breaking down internal silos and setting up robust innovation governance for starters. And very helpful agile innovation management practices supporting disruptive strategy setting and execution.”

Dr. Gerhard Muhrer

Vice President,

Quality Compliance & Systems,

Agilent Technologies

“As innovation management practices evolve, the perspective of CxOs now extends beyond the internal company to the external ecosystem. As a result, CTOs are faced with the need to make decisions about innovation in an increasingly complex business environment. This report provides deep and comprehensive data to generate practical insights for innovation management and ecosystem engagement.”

Prof. Toshiya Watanabe

Executive Director & Vice President,

The University of Tokyo, Japan

“I very much enjoyed reading this insightful report, with its fact-based and industry-specific evaluation of the quality of innovation management. I much appreciated the practical recommendations provided about how companies can capture opportunities in the major improvement domains highlighted and recommend it to any innovation and R&D manager.”

Dr. Yves Van Rompaey

Senior Vice President, Corporate R&D,

Umicore

“This is a highly relevant report. It offers a pragmatic way to the core of managing innovation successfully in today’s context. It looks at best practices across different industry sectors, offering interesting insights and addressing the challenges of managing innovation well in companies with multiple and different business units. All recommendations are stimulating and useful.”

Wim Bouwen

Vice President,

R&D & Shared Engineering Services,

Atlas Copco

“This data-based and sector-specific report about the excellence of innovation management in business today demonstrates that there’s still a lot of room for improvement and makes practical and insightful recommendations for moving forward. In my opinion, innovation management needs more 'brain' and less 'storming'; it needs more strategic thinking and less buzzwords. Let’s work together to turn good innovators into great innovators!”

Prof. Benoit Gailly

Professor/Advisor,

Innovation Management & Strategy,

Louvain School of Management, Belgium

“As the world is going through a major energy and material transition, innovation is more critical than ever for any company to exist and thrive. This report provides insightful analysis that will help those directly or indirectly confronted with the innovation challenge. Key principles to world-class innovation practice are nicely compiled and put in perspective. It gives a roadmap to innovation across disciplines and segments.

A worthwhile read!”

Thierry Materne

Global Head of Technology & Innovation,

Sibelco

“ADL’s GIEB Report is comprehensive, well written, and deals with the current challenges of industry and market stakeholders’ innovation management practices. The pragmatic outlook and opportunities guidance for today’s innovation leaders is of paramount relevance. I very much enjoyed reading this remarkably informative study.”

Alexandre Nussem

Secretary General,

European Industrial Research Management Association (EIRMA)

“This report is a must read for everyone who wants to be inspired by such insightful analysis of current practices in effective innovation management. Based on a large-scale investigation of 500 respondents, ADL succeeds in seamlessly bringing together the best innovation practices in a comprehensive way and explains how innovation excellence relates to breakthrough innovation management practices, business model innovation, transversal communication, agility, and innovation leadership. I’m convinced you will enjoy reading it as much as I did.”

Prof. Wim Vanhaverbeke